by Editor | Oct 24, 2021 | News

3:30 PM – 4:30 PM EST, Oct 28, 2021

Moderator: Ramu Damodaran, first Chief of United Nations Academic Impact, co-chair of the United Nations Centennial Initiative

Speakers: Prime Minister Zlatko Lagumdzija, Harvard Professor David Silbersweig

The moderator and speakers will present and discuss on how Global Enlightenment Education Program of the United Nations Centennial Initiative will contribute to solve the issues of misinformation and disinformation.

This is the first side event to Club de Madrid’s Policy Dialog 2021 “Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment”

The United Nations came into being in 1945 as a cerebral, as much as political, innovation, the very first resolution of its General Assembly, in the January of 1946, was on the “problems arising from the discovery of atomic energy.” 75 years later, in the January of 2021, Governor Michael Dukakis announced the “Artificial Intelligence International Accord Initiative” whose goal he described as “to stimulate a global conversation that will make sure AI is used responsibly by governments and the private sector around the world.” It is precisely conversations of that nature that can nurture an era of global enlightenment as we approach the United Nations centennial in less than a quarter century. An era that can shape a world governed by international law and the exercise of international as much as individual, and indeed intellectual, responsibility where the creativity and innovation of the human person work to shape a world worthy of our times just as surely as that world works to foster and further, in the phrase of the United Nations Charter, the “dignity and worth“ of that human person.

In preparation for that transition and achievement, the Boston Global Forum (BGF) and Club de Madrid are choreographing a series of interviews with eminent thinkers on “Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment” as side events of their joint Policy Dialogue 2021. These will be telecast by major media in Vietnam and in New York and will be accessible on the BGF website.

From Oct 27, 2021 to December 12, 2021:

Format: discussion with selected speakers of CdM Policy Dialog 2021, or distinguished leaders, thinkers, strategists, innovators about Rethinking Democracy

Title of Series: Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment

Topics:

- Global Enlightenment Education to solve Disinformation, Misinformation

- New innovation ecosystems for community innovation economy

- Smart democracy

- AIWS City and Flagship cities in the Age of Global Enlightenment

Moderators: Ramu Damodaran, Professor Thomas Patterson, Professor David Silbersweig, Professor Nazli Choucri

Other side events:

Global Enlightenment Education at UNESCO Global Media and Information Literacy Week 2021

3:30 PM – 4:30 PM EST, Oct 28, 2021

Moderator: Ramu Damodaran,

Speakers: Prime Minister Zlatko Lagumdzija, Harvard Professor David Silbersweig

Building Nha Trang Khanh Hoa in becoming a flagship area in the Age of Global Enlightenment

7:00 AM – 8:30 AM, EST, October 29, 2021

by Editor | Oct 24, 2021 | News

The Framework of Global Laws and Accord on AI and Digital and Global Alliance for Digital Governance were introduced and discussed at the conference “Law and Governance in the Age of AI”, co-organized by Vietnam National University (VNU) and IFI on October 21, 2021.

Scholars of the School of Law, Vietnam National University were pleased to contribute to the initiative of Boston Global Forum, to build the Age of Global Enlightenment.

Presentation

Keynote on Social Contract on the Age of AI and Review on the Book “Remaking the World Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment”

Moderator:

Mr. Nguyễn Anh Tuấn, CEO of The Boston Global Forum (BGF), co-founder of the AIWS City (AIWS.city); Founder, CEO, and Editor-in-Chief of VietNamNet (1997-2011)

Fundamentals of International Law on AI and Digital

Mr. Paul Nemitz, Principal Advisor in the Directorate General for Justice and Consumers, European Commission

Law and governance: a comparative Study on Asian national policies and Strategies

Mr. Đặng Minh Tuấn, Deputy Head of the Constitutional and Administrative Law Department, School of Law, VNU

The Use of AI in Civil Justice System: Perspectives and Challenges for Access to Justice

Mrs. Nguyễn Thị Bích Thảo, Deputy Head of Civil Law Department, School of Law, VNU

The social credit system in china: a state governance system and its adverse impact on human rights

Mr. Nguyễn Văn Quân, School of Law, VNU

Secretary: Mrs. Vu Thi My Le, IFI

by Editor | Oct 24, 2021 | Event Updates

7:00 am – 8:30 am, EST, October 29, 2021

Organizers: Boston Global Forum and Club de Madrid

This is s special side event to Club de Madrid’s Policy Dialog 2021

Moderator:

Thomas Patterson, Co-founder of the Boston Global Forum, Harvard professor, Co-Author of the Book “Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment”

Keynote Speakers:

Governor Michael Dukakis, Co-founder and Chair of the Boston Global Forum, Co-Author of the Book “Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment”

Nguyen Hai Ninh, Chief of Party of Nha Trang Khanh Hoa

Panelists:

Nguyen Tan Tuan, Governor of Nha Trang Khanh Hoa

Ho Van Mung, Chief of Party of Nha Trang City

Alex Sandy Pentland, MIT professor, Co-Author of the Book “Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment”

John Quelch, Co-founder of the Boston Global Forum, Harvard Business School professor

Prime Minister Zlatko Lagumdzija, Co-Author of the Book “Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment”

President Vaira Vike-Freiberga, President of Club de Madrid (2014-2020), Co-Author of the Book “Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment”

David Silbersweig, Harvard Professor, BGF Board Member

David Bray, the top “24 Americans Who Are Changing the World” under 40

Nguyen Anh Tuan, Co-founder and CEO of the Boston Global Forum, Co-Author of the Book “Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment”

by Editor | Oct 17, 2021 | News

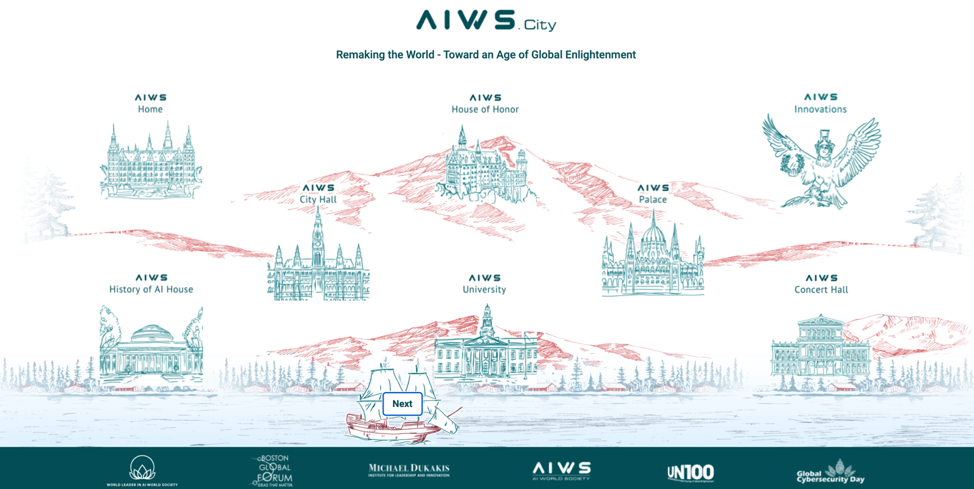

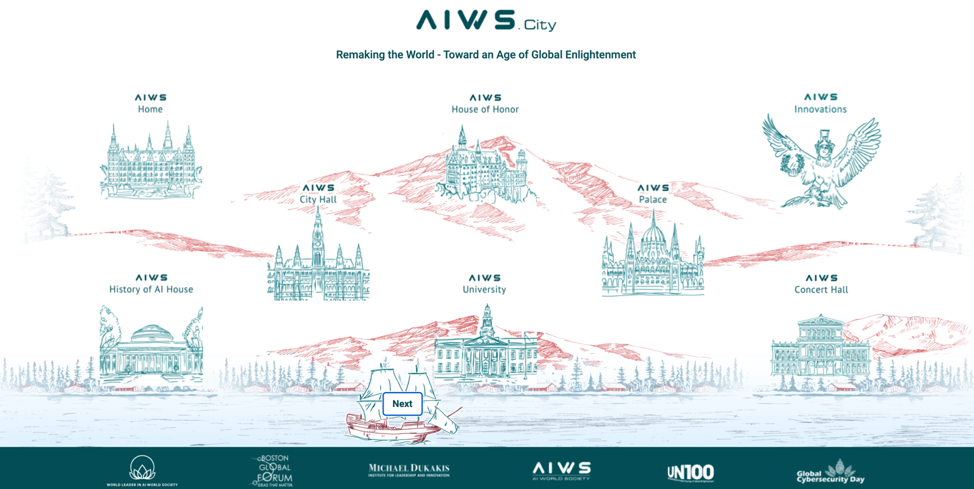

The AIWS Value System is innovative and, as such, untested for its utility. AIWS will test the concept by creating the AIWS City, which will be a virtual digital city dedicated to promoting the values associated AIWS.

Professor Thomas Patterson introduced AIWS City as a practical model for the Age of Global Enlightenment and discuss about it with Moderator Zaneta Ozolina at the session “REMAKING THE WORLD – THE SECOND AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT. THE UNITED NATIONS 2045”, the Riga Conference 2021, October 14, 2021.

The United Nations Centennial initiative was launched by the Boston Global Forum (BGF) and the United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI) in 2019 as the United Nations planned to mark the 75th anniversary the following year. It brought into its fold some of the finest minds of our times as they sought to anticipate the world, and the United Nations, in 2045, the year of the world organization’s centennial. The core concepts of the initiative are reflected in the book “Remaking the World: Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment”; these include the idea of a social contract for the Artificial Intelligence (AI) age, a framework for an AI international accord, an ecosystem for the “AI World Society” (AIWS) and a community innovation economy. Some of these ideas have already begun to be put into practice, including a Global Alliance for Digital Governance and the evolution of AIWS City, a virtual digital city dedicated to promoting the values associated with AIWS.

This session discussed concepts of the book to build the Age of Global Enlightenment, and the particular role of the Baltic States – who celebrate thirty years of United Nations membership this year-in this regard.

Speakers:

Dr Vaira Vīķe- Freiberga, President of the Republic of Latvia from 1999 to 2007

Nguyen Anh Tuan, CEO of the Boston Global Forum, Director of the Michael Dukakis Institute for Leadership and Innovation, Co-Founder of the AI World Society Innovation Network, Co-Founder of AIWS City

Paul F. Nemitz, Director for Fundamental rights and Union citizenship in the Directorate-General for JUSTICE of the European Commission

Alex `Sandy’ Pentland, Director of the Human Dynamics Laboratory, MIT’s, Director of the MIT Media Lab Entrepreneurship Program, Co-Leader of The World Economic Forum Big Data and Personal Data Initiatives, Founding Member of The Advisory Boards for Nissan, Motorola Mobility, Telefonica

Thomas Patterson, Research Director of The Michael Dukakis Institute for Leadership and Innovation, Professor of Government and the Press of Harvard Kennedy School, Distinguished Contributor to the Book “Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment”

Moderator: Prof Žaneta Ozoliņa, Chairwoman of the Latvian Transatlantic Organisation.

Link:

https://fb.watch/8IdvBeUlYR/

and:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cu-2r7qzYZo&t=20490s

by Editor | Oct 17, 2021 | News

Policy Dialogue 2021: Rethinking Democracy

Club de Madrid’s Annual Policy Dialogue will be held on 27, 28, 29 October. Action Labs will take place on 18, 19, 20 October.

The Boston Global Forum (BGF) is a partner of Club de Madrid in organizing the Policy Dialog 2021.

BGF will introduce the book Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment as principles and solutions for Rethinking Democracy.

BGF and Club de Madrid will co-organize special series “Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment”, a dialog between distinguished leaders to build the Age of Global Enlightenment.

The moderators of this special series are Ramu Damodaran, the First Chief of United Nations Academic Impact (2010-2021), co-chair of the United Nations Centennial Initiative, and Harvard professors David Silbersweig and Thomas Patterson.

In spite of its inevitable imperfections, democracy has served humankind well, making systems and institutions stronger, able to meet citizens’ demands. But there is growing evidence that in many places of the world, democracy is wilting away.

Even in established democracies, the level of disruption indicates that our political systems require calibration. Divisive populist discourses, technologies disrupting the public debate, polarized political landscapes and rising authoritarian governance styles, to name a few, are testing the limits of democratic systems across the globe.

Club de Madrid and Boston Global Forum are set on changing the notion that democratic systems can no longer deliver. For our societies to address their many challenges, democracy needs innovation. Club de Madrid’s Annual Policy Dialogue will present far-reaching proposals to adapt our leadership styles, information ecosystems and institutional settings to the realities of the 21st Century. We need to ‘rethink democracy’ and breathe new life into the system.

Link: http://www.clubmadrid.org/policy-dialogue-2021-rethinking-democracy/

by Editor | Oct 17, 2021 | News

Representative of BGF and AIWS.net in Riga, Professor Zaneta Ozolina, Chairwoman of LATO and the Riga Conference 2021, has organized the conference for 2021. The book Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment was discussed at a special session of the Conference. AIWS.net is also glad to introduce the session “Is Data the New Frontier of Power?” of the conference.

Decades have passed since one can consider issues of security at a regional or global level as straight forward melee combat. The number of battle-fronts a country must consider keeps increasing on a regular basis. The most recent tool to be used and targeted is the digital footprint left by any transaction, message or activity in our digital age: data. Unidentifiable resources are invested into gathering as much data as possible to be used for a variety of questionable purposes. How should we reconcile the opportunities and the vulnerabilities that stem with holistic digitalisation? How far should we go to govern the internet, the hardware and the software that enables an unparalleled level of innovation but also the threat of the rise of surveillance capitalism and openings for other national security threats?

Aura Salla, Public Policy Director, Head of EU Affairs at Facebook

Andrejs Vasiljevs, Cofounder and Chairman of the Board of Tilde, Board Member of the Big Data Value Association

Līga Raita Rozentāle, Senior Director of European Cybersecurity Policy, Microsoft

Michael Bociurkiw, Global Affairs Analyst

Josef Schroefl, Deputy Director of the COI Strategy and Defense, European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats (Online)

Moderator: Jānis Sārts, Director, NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence

Link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rlVC9bgNB-8

by Editor | Oct 17, 2021 | News

The Conference “Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Humanity – The Multidimensional Impacts of a Technological Revolution” will take place on October 21th, 2021 in Hà Nội. The event is a part of the DAAS (Diderot Advanced Academic Seminars) series of IFI under the sponsorship of Vietnam National University, Hanoi (VNU), with the collaboration of Vietnam Ministry of Science and Technology.

Speakers:

Paul Nemitz, Principal Advisor in the Directorate General for Justice and Consumers, European Commission, Author of Principle Human – Democracy, Law and Ethics in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, Distinguished Contributor to Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment

Dr. Đặng Minh Tuấn, Deputy Director of the Constitutional and Administrative Law Department, School of Law, VNU

Dr. Nguyễn Văn Quân, Faculty of School of Law, VNU

Dr. Nguyễn Bích Thảo, Faculty of School of Law, VNU

Moderator: Nguyen Anh Tuan, CEO of the Boston Global Forum

Paul Nemitz will talk about his chapter “Fundamentals of International Law on AI and Digital” in Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment and Global Alliance for Digital Government in building the Framework for Global Law on AI and Digital.

Speakers will present the legal system and its implementation in China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia, Singapore, and Vietnam about Law on AI and Digital, and how to engage them to the Global Alliance for Digital Governance.

The outcome of the conference will be a report on the “Framework for Global Law on AI and Digital, a foundation of the Age of Global Enlightenment”

by Editor | Oct 17, 2021 | Event Updates

With Moderator Zaneta Ozolina, Chair Woman of LATO, speakers President Vaira Vike-Freiberga, Professor Alex Sandy Pentland, Professor Thomas Patterson, Paul Nemitz, and Nguyen Anh Tuan presented and discussed about the book Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment with ideas to solve questions at the session “REMAKING THE WORLD – THE SECOND AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT. THE UNITED NATIONS 2045”, the Riga Conference 2021, October 14, 2021.

The age where the impact of AI is only growing, the social contract for the AI Age could be one of the tools which could create a cooperative framework for advancing, managing and monitoring AI and its impact. The authors emphasize the particular role of international organizations. In the last few years, we have been observing the diminishing role of multilateralism. To what extent is the creation of such a Social Contract achievable when it requires commitment from so many parties, the role of education and information in the Age of Global Enlightenment.

The book addresses many issues related to the future of AI. One of the main themes is related to governance- particularly to AI and democratic governance. Concepts such as the next generation democracy are introduced. What makes the next generation democracy different from the present one? What kind of governance is needed for an age of global enlightenment and what is the role of AI?

The foundations of the Social Contract are based on the principle of inclusiveness, to take on the broad range of stakeholders. Have any policy solutions been considered for the containment of actors who violate the agreed principles?

The new concept “Community Innovation Economy” as a fundamental part of the economy in the Age of Global Enlightenment. What are the difficulties in applying it?

What are key factors for world success in building the Age of Global Enlightenment?

AIWS City as a practical model for the Age of Global Enlightenment.

Link:

https://fb.watch/8IdvBeUlYR/

and:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cu-2r7qzYZo&t=20490s

by Editor | Oct 11, 2021 | News

10/10/2020 is birthday of AIWS City, a virtual digital city dedicated to promoting the values associated AIWS.

After one year, AIWS City created Global Enlightenment Community, whose first members are distinguished contributors to the book Remaking the World – Toward an Age of Global Enlightenment.

The Global Enlightenment Community are leaders, strategists, thinkers, and innovators from top 45 cities around the world, such as Boston, NYC, Tokyo, Madrid, Brussels, and others.

The Community promote common values and standards of the Social Contract for the AI Age to the world, reduce extreme nationalism and religious extremism, amongst other goals on territorial integrity.

The Community contribute global educators to build the Global Enlightenment Education Program with key individuals such as: Harvard Professors Thomas Patterson, David Silbersweig, MIT Professor Nazli Choucri, Alex Pentland, Governor Michael Dukakis, President Vaira Vike-Freiberga, Prime Minister Zlatko Lagumdzija, Prime Minister Beatriz Merino, Ambassador Ichiro Fujisaki, Mr. Paul Nemitz, Mr. Ramu Damodaran, and Mr. Nguyen Anh Tuan.