by Admin | Jun 1, 2015 | Statements, News

A recently published article on Asia Sentinel by Bill Hayton, a journalist at BBC World News TV, showed many misconceptions that have slipped into the public discourse on South China Sea disputes, particularly on the dubious evident foundations of some of the English-language writing about its history.

Hayton’s findings showed that the first English-language writings on the disputes were written by Chinese authors and based upon Chinese sources,and so attached with Chinese’s point of view. Almost journalistic articles or think-tank reports writing about the South China Sea disputes in recent years then rely for their historical background on a very small number of papers and books which used unreliable bases from which to write reliable stories.

He also noted that ” It is no longer good enough for advocates of the Chinese claim to base their arguments on such baseless evidence. It is time that a concerted effort was made to re-examine the primary sources for many of the assertions put forward by these writers and reassess their accuracy.”

Read Hayton’s full research here or visit the Asia Sentinel’s website.

Fact, Fiction and the South China Sea

May 25, 2015 | By Bill Hayton

(Photo credit: Asia Sentinel)

In just a few weeks, international judges will begin to consider the legality of China’s “U-shaped line” claim in the South China Sea. The venue will be the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague and the court’s first step – during deliberations in July – will be to consider whether it should even consider the case.

China’s best hope is that the judges will rule themselves out of order because if they don’t, and the Philippines’ case proceeds, it’s highly likely that China will suffer a major embarrassment.

The Philippines wants the Court to rule that, under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), China can only claim sovereignty and the rights to resources in the sea within certain distances of land territory. If the court agrees, it will have the effect of shrinking the vast “U-shaped line” to a few circles no more than 24 nautical miles (about 50km) in diameter.

China is not formally participating in the case but it has submitted its arguments indirectly, particularly through a “Position Paper” it published last December. The paper argued that the court shouldn’t hear the Philippines’ case until another court had made a ruling on all the competing territorial claims to the different islands, rocks and reefs. This is the issue that the judges will have to consider first.

China’s strategy in the “lawfare” over the South China Sea is to deploy historical arguments in order to outflank arguments based on UNCLOS. China increasingly seems to regard UNLCOS not as a neutral means of resolving disputes but as a partisan weapon wielded by other states in order to deny China its natural rights.

But there is a major problem for China in using these historical arguments. There’s hardly any evidence for them.

This isn’t the impression the casual reader would get from reading most of the journalistic articles or think-tank reports written about the South China Sea disputes in recent years. That’s because almost all of these articles and reports rely for their historical background on a very small number of papers and books. Worryingly, a detailed examination of those works suggests they use unreliable bases from which to write reliable histories.

This is a significant obstacle to resolving the disputes because China’s misreading of the historical evidence is the single largest destabilizing factor in the current round of tension. After decades of mis-education, the Chinese population and leadership seem convinced that China is the rightful owner of every feature in the Sea – and possibly of all the water in between. This view is simply not supported by the evidence from the 20th Century.

Who controls the past, controls the future

The problem for the region is that this mis-education is not limited to China. Unreliable evidence is clouding the international discourse on the South China Sea disputes. It is skewing assessments of the dispute at high levels of government – both in Southeast Asia and in the United States. I will use three recent publications illustrate my point: two 2014 “Commentary” papers for the Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore written by a Chinese academic Li Dexia and a Singaporean Tan Keng Tat, a 2015 presentation by the former US Deputy-Ambassador to China, Charles Freeman at Brown University and a 2014 paper for the US-based Center for Naval Analyses.

What is striking about these recent works – and they are just exemplars of a much wider literature – is their reliance on historical accounts published many years ago: a small number of papers published in the 1970s, notably one by Hungdah Chiu and Choon‐Ho Park; Marwyn Samuels’ 1982 book, Contest for the South China Sea; Greg Austin’s 1998 book China’s Ocean Frontier and two papers by Jianmeng Shen published in 1997 and 2002.

These writings have come to form the conventional wisdom about the disputes. Google Scholar calculates that Chiu and Park’s paper is cited by 73 others, and Samuels’ book by 143. Works that quote these authors include one by Brian Murphy from 1994 and those by Jianming Shen from 1997 and 2002 – which are, in turn, quoted by 34 and 35 others respectively and by Chi-kin Lo, whose 1989 book is cited by 111 other works. Lo explicitly relies on Samuels for most of his historical explanation, indeed praises him for his “meticulous handling of historical data” (p.16). Admiral (ret) Michael McDevitt, who wrote the forward to the CNA paper, noted thatContest for the South China, “holds up very well some 40 years later.”

These works were the first attempts to explain the history of the disputes to English-speaking audiences. They share some common features:

- They were written by specialists in international law or political science rather than by maritime historians of the region.

- They generally lacked references to primary source material

- They tended to rely on Chinese media sources that contained no references to original evidence or on works that refer to these sources

- They tended to quote newspaper articles from many years later as proof of fact

- They generally lacked historical contextualizing information

- They were written by authors with strong links to China

The early works on the disputes

English-language writing on the South China Sea disputes emerged in the immediate aftermath of the “Battle of the Paracels” in January 1974, when PRC forces evicted Republic of Vietnam (“South Vietnam”) forces from the western half of the islands.

The first analyses were journalistic, including one by Cheng Huan, then a Chinese-Malaysian law student in London now a senior legal figure in Hong Kong, in the following month’s edition of the Far Eastern Economic Review. In it, he opined that, “China’s historical claim [to the Paracels] is so well documented and for so many years back into the very ancient past, that it would be well nigh impossible for any other country to make a meaningful counter claim.” This judgement by a fresh-faced student was approvingly quoted in Chi-Kin Lo’s 1989 book “China’s Policy Towards Territorial Disputes.”

The first academic works appeared the following year. They included a paper by Tao Cheng for the Texas International Law Journal and another by Hungdah Chiu and Choon‐Ho Park for Ocean Development & International Law. The following year, the Institute for Asian Studies in Hamburg published a monograph by the German academic, Dieter Heinzig, entitled ‘

Cheng’s paper relied primarily upon Chinese sources with additional information from American news media. The main Chinese sources were commercial magazines from the 1930s notably editions of the Shanghai-based Wai Jiao Ping Lun [Wai Chiao Ping Lun] (Foreign Affairs Review) from 1933 and 1934 and Xin Ya Xiya yue kan [Hsin-ya-hsi-ya yueh kan] (New Asia Monthly) from 1935. These were supplemented by material from the Hong Kong-based news magazine Ming Pao Monthly from 1973 and 1974. Other newspapers quoted included Kuo Wen Chou Pao (National News Weekly), published in Shanghai between 1924 and 1937, Renmin Ribao [Jen Ming Jih Pao](People’s Daily) and the New York Times. Cheng didn’t reference any French, Vietnamese or Philippine sources with the exception of a 1933 article from La Geographie that had been translated and reprinted in Wai Jiao Ping Lun.

The paper by Hungdah Chiu and Choon‐Ho Park relied upon similar sources. In crucial sections it quotes evidence based upon articles published in 1933 in Wai Jiao Ping Lun and Wai Jiao Yue Bao [Wai-chiao yüeh-pao] (Diplomacy monthly), and Fan-chih yüeh-k’an [Geography monthly] from 1934 as well as Kuo-wen Chou Pao[National news weekly] from 1933 and the Chinese government’s own Wai-chiao-pu kung-pao, [Gazette of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs]. It supplements this information with material gathered from a 1948 Shanghai publication by Cheng Tzu-yüeh, Nan-hai chu-tao ti-li chih-lūeh (General records on the geography of southern islands) and Republic of China government statements from 1956 and 1974.

Chiu and Park do use some Vietnamese references, notably eight press releases or fact sheets provided by the Embassy of the Republic of Vietnam in Washington. They also refer to some, “unpublished material in the possession of the authors.” However, the vast majority of their sources are from the Chinese media.

Writing a year later, Dieter Heinzig relied, in particular, on editions of two Hong Kong-based publications Ch’i-shih nien-tai (Seventies Monthly) and Ming Pao Monthlypublished in March and May 1974 respectively.

What is significant is that all these foundational papers used as their basic references Chinese media articles that were published at times when discussion about the South China Sea was highly politicised. 1933 was the year that France formally annexed features in the Spratly Islands – provoking widespread anger in China, 1956 was when a Philippine businessman, Tomas Cloma, claimed most of the Spratlys for his own independent country of “Freedomland” – provoking counterclaims by the RoC, PRC and Republic of Vietnam; and 1974 was the year of the Paracels battle.

Newspaper articles published during these three periods cannot be assumed to be neutral and dispassionate sources of factual evidence. Rather, they should be expected to be partisan advocates of particular national viewpoints. This is not to say they are automatically incorrect but it would be prudent to verify their claims with primary sources. This is not something that the authors did.

The pattern set by Cheng, Chiu and Park and Heinzig was then repeated in Marwyn Samuels’ book Contest for the South China Sea. Samuels himself acknowledges the Chinese bias of his sources in the book’s Introduction, when he states “this is not a study primarily either in Vietnamese or Philippine maritime history, ocean policy or interests in the South China Sea. Rather, even as the various claims and counterclaims are treated at length, the ultimate concern here is with the changing character of Chinese ocean policy.” Compounding the issues, Samuels acknowledges that his Asian research was primarily in Taiwanese archives. However, crucial records relating to the RoC’s actions in the South China Sea in the early 20th Century were only declassified in 2008/9, long after his work was published.

There was another burst of history-writing in the late 1990s. The former US State Department Geographer turned oil-sector consultant Daniel Dzurek wrote a paper for the International Boundaries Research Unit of the University of Durham in 1996 and a book by an Australian analyst Greg Austin was published in 1998. Austin’s historical sections reference Samuels’ book, the paper by Chiu and Park, a document published by the Chinese Foreign Ministry in January 1980 entitled “China’s indisputable sovereignty over the Xisha and Nansha islands” and an article by Lin Jinzhi in the People’s Daily. Dzurek’s are similar.

CLICK HERE to continue reading

by Admin | Jun 1, 2015 | Event Updates

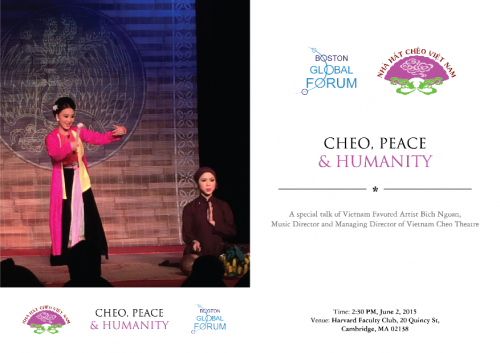

Boston Global Forum is pleased to host a show of Vietnam Cheo Theatre titled, “Cheo, Peace and Humanity”, at Harvard Faculty Club at 2:30 PM on June 2, 2015.

The Vietnam Cheo Theaatre, led by its Music Director and Managing Director, National Favored Artist Nguyen Thi Bich Ngoan, will perform several feature plays of Cheo, a typical traditional stage music of Vietnam, such as Duyen que (songs about charms of countryside), Thi Mau len chua (the extract of Goddess of Mercy: Thi Mau go to pagoda), Hat Xam Hue tinh (Performance of a Vietnamese classical form of music, Xam), Hau Dong (Seance ritual performances).

The performance is devoted to distinguished delegates of Boston Global Forum, Harvard University, MIT, and other guests of honor such as Ambassador Swannee Hunt, Co-founder of Free for All Concert Fund; March Churchill, Dean Emeritus of New England Conservatory’s Department of Preparatory and Continuing Education, Benjamin Zander, Music Director & Conductor of Boston Philharmonic Orchestra; Larry Bell, Composer & Chair of Music Theory of New England Conservatory, and Professor of Composition at Berklee College of Music; Julie Leven, Violinist, Executive and Artistic Director at Shelter Music Boston.

by Admin | May 12, 2015 | Highlights

Understanding of cyber is still vague. The term “cyber war” is used very loosely for a wide range of behaviors, ranging from simple probes, website defacement, and denial of service to espionage and destruction.

Professor Joseph Nye, Member of Boston Global Forum’s Board of Thinkers and Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor, pointed out four major categories of cyber threats to national security in the recent article on Project Syndicate. They are: cyber war and economic espionage, which are largely associated with states, and cyber crime and cyber terrorism, which are mostly associated with non-state actors. Some early international cooperation to secure cyberspace have been done, mostly to prevent criminals and terrorists. However, the international norms tend to develop slowly.

Read the full article here or visit the Project Subdicate website for more detail.

International Norms in Cyberspace

CAMBRIDGE – Last month, the Netherlands hosted the Global Conference on Cyberspace 2015, which brought together nearly 2,000 government officials, academics, industry representatives, and others. I chaired a panel on cyber peace and security that included a Microsoft vice president and two foreign ministers. This “multi-stakeholder” conference was the latest in a series of efforts to establish rules of the road to avoid cyber conflict.

The capacity to use the Internet to inflict damage is now well established. Many observers believe the American and Israeli governments were behind an earlier attack that destroyed centrifuges at an Iranian nuclear facility. Some say an Iranian government attack destroyed thousands of Saudi Aramco computers. Russia is blamed for denial-of-service attacks on Estonia and Georgia. And just last December, US President Barack Obama attributed an attack on Sony Pictures to the North Korean government.

Until recently, cyber security was largely the domain of a small community of computer experts. When the Internet was created in the 1970s, its members formed a virtual village; everyone knew one another, and together they designed an open system, paying little attention to security.

Click HERE to read the full article.

by Admin | May 21, 2015 | Highlights

Boston Global Forum is deeply concerned over recent events in the Pacific that threaten the peace, security and economic well-being of the region and the world at large. The Framework for Peace and Security in the Pacific has being developed based on accepted principles such as abiding by international law, multilateralism and transparency to avoid conflict.

We are now urging policymakers, and scholars’ insights and ideas regarding current events in the South China Sea, which is the issue of China’s rapid construction activities on the waters of the South China Sea and its announcement of its “nine-dashed-line” claims based on its vaguely-defined notion “historical rights”. As most of experts has said that China’s construction activities could pose direct threat to freedom of navigation and overflight across the South China Sea, threatening not only the territorial claims of other claimant states, but also the national interests of extra-regional powers such as Japan and the United States. The issue that can—through misstep or misunderstanding—result in open and armed conflict.

As we knew UNCLOS is a crucial mechanism to maintain peace and security in the South China Sea. Unfortunately, the United Nations and Arbitral Tribunal seem to lack the power to enforce sanctions and force the countries to respect and comply with UNCLOS in settling disputes.

Boston Global Forum is seeking the answer to these important questions:

- How can the world community force nations to respect and strictly observe the UNCLOS?

- Who will have the power to punish bad actors once a nation does violate the UNCLOS?

In response to these questions, Professor Richard Rosecrance, Adjunct Professor, Harvard Kennedy School; Research Professor of Political Science, University of California, Los Angeles, said “UNCLOS is basically unenforceable”.

Professor Suzanne Odgen, Member of Editorial Board, Boston Global Forum, Professor of Northeastern University’s Department of Political Science,thought that there is no way to “force” respect as most international laws are obeyed on the basis of reciprocity: I will obey it if you obey it. As international law is, like most law, subject to the interpretation of the ‘facts,’ moreover, any sort of juridical process can go on for years while the law is still being disobeyed, questioned, or ignored, etc.

In her view, Professor Odgen added:

As the US has never ratified UNCLOS, it is in a difficult position to discuss ‘enforcement’ or punishment. Most disputes in the international community over matters that are codified in international law are today settled—or remain unsettled and ongoing—by relying on arbitration, negotiation, compromise, etc. the costs/ potential costs of military conflict are enormous—to all sides. Further, the US has to weigh the shifting balance of power in Asia, as well as elsewhere throughout the world, before ever considering the use or threat of use of force. The days when the US could count on other countries, even allies, supporting its efforts to ‘discipline’ bad actors in the international system, are gone, or at least going……

Douglas Coulter, visiting Professor in Guanghua School of Management at Peking University, shared another view. According to him, the United States and apparently the western world have not drawn the lessons from the war in Vietnam, the war in Iraq, and the war in Afghanistan, which is that you can’t force countries from the outside. Changes only are made if they are initiated by the countries themselves.

He also shared his view on recent developments in the South China Sea. In his opinion:

“The worst thing to do is to publicly threaten China over it. In order to soften up China over the South China sea is to have American Secretaries of Defense visit Mongolia or American Admirals publicly advocate joint country patrols in the South China Sea, or for the United States to encourage Japan to get involved.

The only thing that will work with China is to change America’s fundamental relationship with it and not to continue to keep doing the same thing we have been doing since the Vietnamese War.

One of the biggest sources of friction in East Asia is Japan’s refusal to acknowledge its history in the Second World War. China lost three times more people in the war than Japan did. China was occupied. If Japan was freeing the Chinese from colonial occupation, as the Japanese officially claim, why were the Chinese fighting them? Think of what would happen if Merkel visited graves of the SS.

If the United States demanded publicly and uncompromisingly that Japan satisfy completely China’s and Korea’s demands concerning Japan’s role and history in the Second World War, I suggest that this would materially change the United States’ relations with China. Japan could do nothing. If they want an ally to resist China, where are they going to go, except the United States? Are they going to go to India?

If our relations materially changed with respect to China, I suggest we could get a lot more flexibility in other areas, including the South China Sea, as long as we pursued these privately and not with public pronouncements.

But our chances of this may have been permanently destroyed after Abe’s trip to the United States, where he came away with the store, and this trip will continue haunt us. Concerning China’s claims in the South China Sea, this has been on their maps since the People’s Republic came into being in 1949, and they inherited from the Kuomingdang. They didn’t invent it. And presumably the Kuomingdang got it from a much earlier period, the Qing or Ming Dynasties.

One of the most interesting aspects of this dispute, or maybe the least interesting, is that the United States didn’t utter a word about it until around 2006, although there has never been any mystery for years.

The biggest barrier to any easing of the South China Sea issue is the United States, which will continue to browbeat China over it and harden China’s position. The United States, as we have witnessed since the 1960’s, doesn’t know any other approach.

With regard to international laws, since the United States hasn’t signed the Law on the Sea, because there is obviously some clause we don’t want to have to abide by, what international laws are we insisting China respect. The United States itself has a very good record of abiding by international laws, such as the War in Iraq.”

Professor Richard Cooper, Maurits C. Boas Professor of International Economics at Harvard University, added his view concerning the China’s maritime territory claims:

” A recent comprehensive history of the South China Sea can be found in a new book of that title by Bill Hayton, 2014. According to him, the nine-dashed line was first drawn by a Chinese geographer (with no official position I believe) in 1937. I can affirm from my own research on the telegraph in China that the Qing dynasty in the 1870s made no claim to any territorial sea: Chinese sovereignty began at the shoreline.”

———

(to be continued)

by Admin | May 8, 2015 | Highlights

In recent post on The National Interest, Richard Javad Heydarian, an Assistant Professor in international affairs and political science at De La Salle University, and a foreign policy advisor at the Philippine House of Representatives (2009-2015), pointed out that it is no longer easy for America to keep Chinese territorial ambitions in check as it did during the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis, given China’s rapid military modernization since the mid-1990s. Therefore, the challenge to America is how to slow down, if not stop, China’s aggressive posturing without risking a diplomatic breakdown and/or an armed confrontation with China in the western Pacific. And this could very well define Obama’s foreign policy legacy.

The article came out after he attended the Boston Global Forum’s conference on April 20, 2015 focusing on managing peace and security in the South China Sea.

Read his opinions here or visit The National Interest website.

The South China Sea Crisis: What Should America Do about It?

April 29, 2015, By Richard Javad Heydarian

As China rapidly builds facts on the waters of the South China Sea, the United States is confronting a strategic conundrum similar to the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis, when Washington faced a difficult choice between upholding its treaty obligations to an ally (Taiwan) and ensuring freedom of navigation in international waters, on one hand, and maintaining stable ties with a rising power (China), on the other. In a recent conference organized by the Boston Global Forum, which focused on the South China (and where I had the pleasure to be among the invited speakers), Joseph Nye made two important observations regarding China’s ongoing construction activities in the South China Sea. First, he correctly pointed out that the construction activities are neither new nor unique to China. This is true as other claimant states—namely Taiwan, Malaysia, Vietnam, and the Philippines—have been engaged in varying forms of construction activities on disputed features in recent decades.

Occupying the two most prized features in the Spratlys, Taiwan and the Philippines were able to build airstrips and advanced facilities on Itu Aba and Thitu islands, respectively. Asearly as 1995, the United States had to contend with the Mischief Reef crisis, which pit a treaty ally (the Philippines) against an emboldened China, which wrested control of the disputed feature in 1994 and proceeded with establishing a rudimentary military garrison soon after. Secondly, Nye reiterated the fact that China, which occupies about seven features in the Spratlys, trails Vietnam (21) and the Philippines (8). And unlike Taiwan and the Philippines, China wasn’t able to occupy a single island throughout its aggressive scramble in the South China Sea in the last three decades of the 20th century. Left with atolls, rocks, sandbars and other forms of low-tide elevations, China has resorted to building artificial islands.

With these observations in mind, one would be tempted to argue that China is simply catching up with other claimant states. China’s accelerated construction activities, however, standout for at least three reasons. To begin with, China’s coastal real estate gambit is unprecedented in scale, speed, and technological sophistication. No other claimant state comes even close to what China is undertaking in the disputed areas, which is tantamount to nothing less than geo-engineering on steroids. Second, while other claimant states have occupied features that fall well within their 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) as well as their continental shelves, China, in contrast, is trying to achieve de facto sovereignty over features, which fall hundreds of miles away from its southernmost province of Hainan. So far, China’s sweeping “nine-dashed-line” claims in the South China Sea, based on its vaguely-defined notion “historical rights,” has hardly convinced any serious legal scholar outside China. Lastly, China’s construction activities could pose direct threat to freedom of navigation and overflight across the South China Sea, threatening not only the territorial claims of other claimant states, but also the national interests of extra-regional powers such as Japan and the United States.

Read the full article here.

by Admin | May 4, 2015 | Highlights

The U.S have taken no position on the sovereignty issues in the South China Sea, but it strongly agrees that the UN laws should be used to resolve the disputes and develop code of conduct. Managing the U.S and China relation is one of the crucial questions for world peace in the next half century and there is no “necessary conflicts” between them, as Professor Joseph Nye stated in his speech in the Boston Global Forum’s conference on managing the peace and security in the South China Sea, which was held on April 20, 2015 at Harvard Faculty Club.

Professor Joseph Nye, member of Boston Global Forum’s Board of Thinkers, Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor was co-moderator in the BGF conference in April 20, 2015.

He also stressed that, the U.S should stand still on the sovereignty issues in the South China Sea, but “take a clear position on keeping an open environment by U.S laws and entreaties and encourages joint exploitation of resources.

Read his full transcript of speech below.

Professor Joseph S. Nye Transcript

Boston Global Forum Conference, April 20th 2015

“It’s worth noticing that the headlines in the NY Times last week were part of what we are talking about. There was a picture on the front page of the Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly islands , and the new runway that China is building, which is supposedly going to be 2 mile long, capable of accommodating any kind of military aircraft. This is a reef about 1000 miles South of Hainan. So there is a high degree of concern, some people say that once the Chinese have built the airfield on Fiery Cross Reef, they will then declare an Air Defense Identification Zone, similar to what they declared in the East China Sea. This is part of the plan to close off the South China Sea. US should be careful not to be too alarm. We’ve been through this before in 1995, there was a great deal of alarm about the fact that China is constructing structures on Mischief Reef, which is about a hundred miles from Fiery Cross Reef and also Spratly islands. At that time, the U.S stated that we would take no position as a country on the sovereignty issues in the South China Sea because they are far too complex and there are too many conflicting claims, not just from China but also from other Asian countries. The US had no position on the sovereignty, but it did take a strong position on the idea that the seas should be governed by the UN laws, which the U.S regards as the international law. Also we urge the parties involved to find peaceful ways to resolve the disputes and develop codes of conduct. That has been the American position since then. The question is should this position change. Are we seeing something we should lead to a difference, where the Americans take a tougher position in the South China Sea?

I think it helps to put this into a broader context of the US and China relations. I think managing US and China relation in the next half century or so is one of the crucial questions for world peace. As I argue in my new book: “Is the American century over?” I think we can manage that relationship. I don’t see necessary conflicts between the US and China. And we have to be careful not to overreact. On the other hand we have to make sure that our interests and our allies are protected. I should also note that the South China Sea is different from the East China Sea. In the East China Sea, where there is dispute between China and Japan over Chinese Diaoyu Islands and Japanese Senkaku Islands. We have a very clear position which is the Senkaku Islands are in the US-Japan security treaty. They are covered by the treaty, and the President has said this himself. So in the East China Sea there is no question. When the China declare the Air Defense Identification Zone in East China Sea, one of the first things the United States did was to show that we did not recognize that. So East China Sea is treated separately.

In South China Sea, we do not have that same alliance relation. There is no alliance with the Philippines. And the question of how much the United States should be involved in the details of various disputes is the theme debated in Washington now. There are a number of proposals of what the US policy should be, whether we should depart from the policy in 1995. One interesting proposal is made by Charles Freeman. Freeman points out that if we look at the Spratly Islands, there are 44 features, rock, shoals, and so forth, which are occupied. And that in fact is all the occupation. The number of features in the sea could be occupied by the states is divided so that everybody gets a piece. This argument is that we all have a standstill instead of to solve all this out by some sort of overall formula. To say the standstill under international law will keep this situation without change.

Now interestingly, if we keep that position, guess who would get the most out of it? Vietnam, which occupies 25 of these features, just in the Spratly Islands. Second is the Philippines, which occupies 8. Third is China which occupies 7. Fourth is Malaysia which occupies 3 and fifth is Taiwan which occupies 1. One of the interesting questions about this proposal is would China agree through it? Because it clearly means that other states also get into the occupation, but it is an interesting proposal because instead of trying to sort out all these issues, you can say let the occupation spread where it is now and perhaps you will have the incentive for joint exploitation of resources, or if you are finding ways to negotiate or compromise over the conflict.

The second proposal is made by Bonnie Glaser at Center for Teaching International Relations Studies, which takes slightly tougher position. Bonnie recommends that China has not developing code of conflict with the Asian countries which she regards or the Asian countries regard as unsatisfactory, let the Asian countries develop their own code of conflict and ways to resolve these issues, and let that China to sign on the form, and put ASEAN in a higher position.

The second thing she recommends is that U.S should help Philippines and Vietnam to improve their police capacity, particularly strengthen their coast office, as recently U.S’ announced programs could actually do help those countries in the region. This is important as you remember that China installed an oil drill in Paracel Island, leading to the seventy days of conflict between China and Vietnam. Most of this battle of ships, eventually it changed where they were ending China’s riot on land in Vietnam; the China realized that they had to find some way to make sure that they do not ruin their relationship with Vietnam overall.

The third thing that Bonnie recommends in her paper is that we state in advance that we will not recognize, so try to deter China from announcing those.

And the forth she recommends is to develop the military relationships between U.S and China, which deals with incidences of sea but led to this agreement on how to reduce air conflict. These principles like these will help solve the problem that we hope to prevent from escalating.

Now the question is how do we get to do this? The Freeman principle, essentially a standstill with the American power and position they have had since 1995, which were reiterated by Hilary Clinton in Hanoi in 2010, we would say everybody stay still and start developing principles for joint exploitation of resources. One problem is that the China is not standing still with building in the Paracel Islands. There is a facetious but understandable remark that China is building a Great Wall of Sand in the South China Sea. If China has stopped, it would be feasible, but since China hasn’t stopped construction, there is difficulty to reach proposal. On the other hand, if you take Bonnie’s proposal, the question is how much the United States wants some of these issues. From a historical point of view, the claims are very ambiguous. Some of the claims are clear, but some are very confusing. The U.S should be careful not to get into a position where we have so much to do with China that we end up fighting over some acres. Are we really willing to get into a situation like this? South China Sea, unlike East China Sea is not clear, and we should not treat South China Sea the same as East China Sea and wind up elaborate cost between U.S and China. I think the 1995 position is still correct, that we should not take position on the sovereignty of various features of the sea, but take a clear position on keeping an open environment by U.S laws and entreaties and encourage jointexploitation of resources.

So that’s my summation of where we are standing now.”

by Admin | Apr 22, 2015 | News

“It’s so early that it has no headquarters, secretariat or paid staff. But this nascent think tank has gathered a loose faculty from a coterie of public intellectuals, mainly in and around Boston, and abroad in Hanoi, Tokyo and Berlin. – It’s called the Boston Global Forum.” Llewellyn King shared his views about the Boston Global Forum in the Huffington Post.

Llewenlyn King is a journalists, co-host and Executive Producer of the PBS’s “White House Chronicle”.

Read his full article here or visit the Huffington Post website.

Birth of an Institution in Boston

04/07/2015 by Llewellyn King

Do think tanks really think? It’s not that these organizations — mostly centered in Washington, D.C., but also scattered across the country — don’t harbor some fine minds among their scholars and fellows, but the problem is we know what they think — and have often known for a long time. The rest is articulation.

Among Washington think tanks, we know what to expect from the Brookings Institution: earnest, slightly left-of-center analysis of major issues. Likewise, we know that the Center for Strategic and International Studies will do the same job with a right-of-center shading, and a greater emphasis on defense and geopolitics.

What the tanks provide is support for political and policy views; detailed argument in favor of a known point of view. By and large, the verdict is in before the trial has begun.

There a few exceptions, house contrarians. The most notable is Norman Ornstein, who goes his own way at the conservative American Enterprise Institute (AEI). Ornstein, hugely respected as an analyst and historian of Congress, often expresses opinions in articles and books which seem to be wildly at odds with the orthodoxy of AEI.

A less-celebrated role of the thinks tanks is as resting places for the political elite when their party is out of power. Former U.N. ambassador John Bolton, rumored to be favored as a future Republican secretary of state, is hosted at AEI. National Security Adviser Susan Rice was comfortable at Brookings between service in the Clinton and he Obama administrations. At any time, dozens of possible office holders reside at the Washington think tanks, building reputations and waiting.

My interest in think tanks and their thinkers has led me to what might be developing into a think tank, although it’s too early to say. It’s so early that it has no headquarters, secretariat or paid staff. But this nascent think tank has gathered a loose faculty from a coterie of public intellectuals, mainly in and around Boston, and abroad in Hanoi, Tokyo and Berlin.

It’s called the Boston Global Forum. Formed in 2012, it’s led by two very different but, apparently, compatible men: Michael Dukakis, former Massachusetts governor and Democratic presidential nominee, and Nguyen Anh Tuan, who founded a successful internet company in Vietnam and now lives in Boston.

The concept of the forum is to study and discuss a single topic for a year. Last year, in forums and internet hookups between Boston and Asian and European cities, the topic was security in the South and East China seas, where war could easily erupt over territorial disputes. After a year of discussion, the participants concluded that a framework for peace in the region needs to be established and that current international arrangements and organizations don’t go far enough in that direction. This year’s topic is cybersecurity.

The Boston Global Forum has strong ties to the faculties at Harvard and Northeastern University, where Dukakis is a professor. Most forum meetings take place on the Harvard campus. Two of the forum’s most conspicuous champions are Harvard professors Joseph Nye and Tom Patterson. Patterson’s office at the John F. Kennedy School of Government serves as a kind of de facto headquarters.

This new entrant into the think tank cohort is very East Coast-tony, and very energetic. This year it has plans for meetings in Vietnam, Tokyo and somewhere in Europe, and has attracted media heavyweights like David Sanger of The New York Times and Charles Sennott, one of the founders of the online GlobalPost.

As the Boston Global Forum is a new think tank, questions abound: Will it get funding? Will it find premises and staff ? Will it get public recognition?

The big question about anything that looks like a think tank is, will thinking happen there? Will the Boston Global Forum be a crucible for big ideas? Or will it, like other think tanks, develop its own binding ideology?

Will the Boston Global Forum become, like so many, a smooth propaganda machine? Or will it be a place where the outlandish can live with the orthodox?

by Admin | Apr 22, 2015 | Event Updates

(March 31,2015) – During the trip to Tokyo to organize the Boston Global Forum’s first conference about its Young Leaders Network, Governor Michael Dukakis, Co-founder and Chairman of the Boston Global Forum made a speech at Meiji University about Creating a Framework for Peace and Security in the Pacific.

Read his full speech here.

CREATING A FRAMEWORK FOR PEACE AND SECURITY IN THE PACIFIC

Meiji University, Tokyo- March 30, 2015

It is a real pleasure for Kitty and me to join you in this historic city for a conference that is dealing with one of the great challenges we face as we seek to create what the first President Bush called “ a new world order.”

When he and Mikhail Gorbachev agreed to end the Cold War, many of us looked forward to an era which would be radically different from what we had experienced during the decades following World War II. We believed that it was possible to develop new institutions and rules of conduct that would not only reject war as an acceptable solution to the world’s problems but would make it possible for us to take the billions we were pouring into weapons of wars and use them to make this world a much better place.

Our thanks to Meiji University for inviting Kitty and me and making it possible for all of us to stop, take stock, and ask ourselves how well we are achieving the goals that Presidents Bush and Gorbachev set for us and for the world some twenty-five years ago.

I say this as somebody for whom Japan is not a new place. I served in the U.S. Army in Munsan, Korea from 1955 to 1957 about seven miles from the demilitarized zone. Fortunately for me, an uneasy truce was in effect, and those of us who were serving in Korea could take a week of leave in Japan every four months during our sixteen month tour of duty. That meant that I had three weeks in addition to whatever leave time I chose to take to spend in Japan, and, believe me, I made full use of it. I covered the country; explored its cities and its countryside; tried the best I could to study its history and its efforts to rebuild after World War II both physically and politically; and was impressed with the fact that Japan for the most part had accepted the Allies’ insistence that it forego rearmament and do in the Pacific what we hoped Germany would do in Europe— play the role of peacemaker in their respective regions.

At the same time an emerging Communist China had defeated the Nationalists and was advocating a tough and belligerent approach to foreign affairs allied with what we then called the Soviet Union. The Cold War that emerged engulfed everyone everywhere. The U.S. and the Soviet Union began to intervene in virtually every part of the globe. That included Vietnam—and another war which took thousands of American and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese lives before it ended in defeat for the U.S.

By contrast, Japan’s recovery was remarkable. It began building an impressive, modern economy; found itself competing effectively with the U.S. and other advanced industrialized nations, In fact, many of you will remember that my friend, Ezra Vogel, wrote a popular book called “ Japan as Number One” that stirred up a lot of interest in the U.S. and around the globe. I always thought that the fact that Japan did not have to devote billions for its defense was one of the reasons it was able to develop its peacetime economy so effectively; give us remarkable technological advances like high speed rail; and establish itself as a serious international player in the world economy.

My own view of the subject of this conference has been influenced by two things: a strongly internationalist view of the world and the lessons one learns from a long and active life of public service over many decades.

I just celebrated my eighty-first birthday this past November. Kitty and I were children during World War II and remember it well. Almost within months after it ended, the Cold War began and engulfed us all for nearly fifty years. So most of our adult lives until the Cold War ended were defined by the struggle between the U.S. and the Soviet Union; communism and capitalism; east and west.

Fortunately, all of that is—or should be—behind us. India and China are emerging as growing economic players in a new world economic order. Japan, while it has had its economic struggles lately, continues to be an important force in Asia and the world.

I say “ should be” because there are increasingly troubling signs that some elements of the international community are beginning to accept the inevitability of a new Cold War in which Asia and the Pacific will be one of its battlegrounds. Clearly, in a world of imperfect human beings, there will be pressures and conflicts. That is why we have the United Nations and the various regional organizations under it that seek to create a framework for peace and security within their regions and try to resolve their differences peacefully and constructively.

In the Western Hemisphere, for example, we now have the Organization of American States that has done much to end the constant conflict that plagued the region for centuries and the military dictatorships that ruled much of it. In fact, when I was a student at the University of San Marcos in Lima, Peru in 1954, there were no more than three genuinely democratic governments in all of Latin America.

These days virtually all of Latin America is governed by democratic governments, and those that aren’t are under strong regional pressure to move in that direction. That includes Cuba which at long last will finally be able to function without the crushing effect of a U.S. imposed and enforced embargo and will have at long last the opportunity to evolve into a healthy and genuine democracy.

I cite the OAS as one example of the regional institutions under the aegis of the United Nations which can serve as models- however imperfectly- for the kind of permanent Asian regional organization that in my judgment is absolutely essential if we are going to achieve the goals that are reflected in this conference. Moreover, the OAS has not limited itself simply to reducing and eliminating conflict. When I spent that summer in Peru in 1954, one out of every two Peruvian babies never lived to see its first birthday. Today, infant mortality in Peru is about where it is in the rest of advanced industrialized world—a victory for the kind of international public health effort under the UN that most recently ended the Ebola epidemic remarkably quickly and effectively.

But I find the current situation in Asia and the Pacific particularly troubling. After decades of turmoil and conflict, the region has now achieved a remarkable level of growth and confidence and relative peace.

The China of Mao has now become a very different and, I would argue, better place. It has essentially adopted a market economy, and while it has not embraced democracy, I believe that will be inevitable over time as it grows in economic strength and influence and reaches out, as it is now doing, to nations all over the world. Welcoming and not rejecting China into the family of nations will encourage that development, which is why the U.S. effort to stymie China’s proposed international development bank and keep its key allies from joining it seems so short sighted.

The developing world, and particularly Asia, need the trillions in foreign exchange that China can help to pour into the new bank. For the life of me, I can’t understand why the U.S. or others would object to it. In fact, by participating in it and encouraging others to do so, we can ensure that it meets high standards of fiscal and banking responsibility and include China and others even more fully in an increasingly collaborative world that shares its resources.

South Korea is a marvel. The country I left as a young GI in 1957 with a per capita annual income of $50 is now a remarkable example of economic and political transformation. The dictatorship of Sygman Rhee is a distant memory as are the military dictatorships that followed it. Genuinely democratic institutions exist and thrive. Only the continued instability that North Korea creates casts a shadow over a prosperous and successful Korean future—an important priority for the kind of regional organization that I think is essential to the region’s future.

There are, as all of you here know, other critical issues that cry out for regional collaboration and resolution.

1. Political developments in Thailand are troubling and must be resolved if the Thais are going to get back on course with the peaceful and successful evolution of their democracy. Military dictatorships, as we all know, get into trouble sooner or later. A genuine effort to return Thailand on the road to democracy is essential– the sooner, the better.

2. You are now trying to deal with a series of disputes over islands, many of which are relatively worthless but seem to carry with them historic significance for certain countries and some of which do include resources that could be helpful to region as a whole. China has been particularly aggressive in establishing its presence and pursuing its claims, but Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam and others have not been shrinking violets on the subject. These claims will never be resolved unless they are taken to an international dispute resolution tribunal like the World Court or the Law of the Sea tribunals or, conceivably, new machinery covering the region itself to be created by the proposed regional organization. China seems to prefer bilateral negotiations on the island questions, but there are too many countries and too many interests to be resolved bilaterally in most of these cases. A regional organization that either creates its own approach to resolving these issues or uses existing international machinery is the only way they can be resolved peacefully and effectively, and it is important that all of the nations involved, including China, recognize this.

3. The remilitarization of Japan is a particularly troubling issue. Frankly, I don’t see how the renunciation of the post-World War II Japanese constitution contributes to the creation of a framework for peace and security in the Pacific. In fact, I believe that Japan should play a unique role in the region as a peacemaker

4. The way Germany has conducted itself and continues to conduct itself since World War II is a good model to follow. It has certainly played a very constructive role in post-World War II Europe. It has been particularly important in attempting to deal with the current problems in Eastern Europe. Japan has exactly that same opportunity in the Pacific, and I believe it should use it; save itself a lot of money that it can use far more constructively for other priorities both at home and throughout the region; and continue to rely on the U.S. guarantee of its security which nobody I know in the U.S. questions.

5. Terrorism is the one issue on which virtually all established governments agree, and those that don’t are or will be quickly isolated. We all feel terrible about the victims of ISIS or the Taliban or other terrorist attacks and the various armed assaults that are taking place frequently throughout the world and take human lives. I don’t for a minute, however, believe that they are an existential threat to world order or democracy and freedom. They will be crushed quite simply because established governments won’t tolerate them. If one of those established governments in the Middle East happens to be Iran, so be it.

6. The U.S. may have its issues with China and Russia, but the active participation of both of them and the progress made so far in the ongoing negotiations with Iran over its nuclear energy policy would have been impossible without them. If the dispute with Iran is resolved, that would be a good starting point for similar negotiations with North Korea. Progress begets progress in this world. This might well be one good example of it.

7. Climate change is, however, an existential threat that must be taken seriously. While a majority of the members of the U.S. Congress apparently don’t share that view and the new Senate majority leader is actively trying to mobilize some of the states in the U.S. in opposition to what he calls President Obama’s “War on Coal,” anybody with half a brain who looks at the evidence has to conclude that human activity is creating a very serious long term threat to the viability of the planet. In this respect the recently concluded agreement between the U.S. and China is good news indeed. Let’s see if we can build on that. Let’s see if we can persuade the new Indian prime minister that mining and burning all the coal in India is not the way to go. China should play a major role in that effort.

8. It’s time for an international conference on cyber warfare. China and the U.S. in particular have been engaging in a cyber cold war that certainly isn’t contributing to peace and security in the region or, for that matter, the world, and I am sure we are not alone. Why isn’t the international community doing something about it? Why aren’t we trying to create the cyber warfare equivalent of the International Atomic Energy Commission? Why aren’t we pushing hard for international standards and enforcement machinery that can stop this madness before it spirals out of control? The head the U.S. National Security Agency recently argued that the U.S. had to begin spending billions more on offensive cyber weapons at a time when my country needs those billions to invest in its own public infrastructure

9. Finally, and most troubling, is the past and current situation with North Korea. Clearly, it is a dangerously isolated country. Its people are starving while it spends millions on nuclear weapons development. Several months ago, the Chinese president visited South Korea, and his visit immediately produced comments in the west that the visit was designed to drive a wedge between South Korea and the U.S. Rather than an effort to damage U.S. ties with South Korea, his visit seemed to me to be a strong message from him to North Korea that China was getting fed up with the North and looked forward to a constructive relationship with the South. Isn’t that a good thing?

Clearly, there are powerful forces in the region and the world, including the UN Security Council, that are committed to stopping nuclear proliferation and prepared to work together to do so. We don’t know at this point if the negotiations with Iran are going to be successful, although certainly much progress has been made.

In the meantime, why not begin to work on a similar process that focuses on North Korea? Why not seriously explore the same kind of serious, science based effort that has for the most part characterized the Iranian negotiations despite the active opposition of right wing Iranian, Israeli and U.S. political forces?

What better time to launch this effort, especially if it comes on the heels of a successful conclusion to the negotiations with Iran? The Iran model doesn’t have to be followed to the letter. Other nations in the region like Japan and South Korea should be involved as Germany has been in the Iranian negotiations, but having the permanent members of the Security Council driving the process has been critically important in the case of Iran and will be equally important if we are to bring the North Koreans to the table and make them a part of the solution and not the problem.

Here I think the Secretary-General of the UN can and should play a major role. He carries with him the prestige of the office. He is Korean with long experience in international affairs. He is a patient and skilled negotiator. He will have the broad support of the international community. He should be a key participant in this effort.

That’s a heady agenda for those who believe, as I do, that creating the kind of framework that we will be discussing at this conference is not only important but eminently doable. Does it require a high degree of optimism? Of course it does, but my experience teaches me that pessimists don’t succeed in public life. If you don’t believe that good people, working together, can make a difference in this world, then you should try something else.

Fortunately, there are a lot of optimists in this world. Many of them, I hope, are here with us at this conference, and I am looking forward to our discussion and to what I hope will be concrete proposals for change and institution building that can set the stage for real progress..

What kind of regional organization would make sense? Can it build on existing ones or should it be created as a new entity? What kind of a charter should it have? What rules of conduct for its members should it seek to enforce? What will be its relationship to the UN itself? Should it have new dispute resolution authority? And what role, if any, should the United States play in it?

Of course, we want a Pacific and an Asia that is open to all countries and all kinds of economic and maritime activity. We want a Pacific and an Asia which are forces for peace and progress—peace and progress that are broadly shared and help to build the kind of world we want for our children and grandchildren. But that vision must be primarily the product of regional leadership and regional cooperation.

In doing so, it would be wise to heed the words of another son of Massachusetts who was born just minutes from where Kitty and I have lived and raised a family in our native town of Brookline.

“What kind of peace do we seek, “John Kennedy asked. “ Not a PAX Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war. Not the peace of the grave or the security of the slave, but a genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life worth living. Not merely peace in our time but peace in all time.

“The pursuit of peace,” he said, “is not as dramatic as the pursuit of war. But we have no more urgent task. Too many of us think it is impossible. Too many think it is unreal. But that is a dangerous, defeatist belief…No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings.

“History teaches us,” he said, “that enmities between nations, as between individuals, do not last forever. The tide of time and events will often bring surprising changes in the relations between nations. {We should not} see conflict as inevitable, accommodation as impossible, and communication as nothing more than an exchange of threats.”

“For in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.”

Governor Michael Dukakis

by Admin | Apr 21, 2015 | Highlights

(20 April, 2015) – A conference on finding solutions to manage peace and security in the South China Sea was held successfully by Boston Global Forum, attracted participation and contribution of several delegates who are policy makers, practitioners, scholars, and researchers from Cambridge, Washington DC, Tokyo, Manila and Vietnam.

Various insights, reports and opinions were given and shared by participants. A special report on current developments in the South China Sea was presented

The conference was moderated by Governor Michael Dukakis and Professor Joseph Nye

Mr. Admiral Nirmal Verma, the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations Distinguished International Fellow in U.S. Naval War College – Newport RI, and former India’s High Commissioner to Canada (2012-2014), Former Chief of Naval Staff of Indian Navy attended the conference

Professor Thomas E. Patterson introduced the report on the South China Sea

Mr. Michael H. Fuchs, U.S. Department of State’s Deputy Assistant Secretary for Strategy and Multilateral Affairs in Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs joined the discussion from Washington DC via video conference

The discussion also featured delegates from Tokyo: Mr. Fumio Ota, the Former Professor at Defense Academy of Japan (2005 – 2013) and Ambassador Ichiro Fujisaki, the President of the America-Japan Society, Inc, Professor of Sophia University and Keio University, and former ambassador of Japan to the United States of America (2008-2012).

Mr. Thomas J. Vallely, Member of Board of Thinkers of Boston Global Forum; Senior advisor of Mainland Southeast Asia, and staff at Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard Kennedy School gave his comment

Ms. Lei Guo, the Assistant Professor of Division of Emerging Media Studies at Boston University College of Communication made her points