by Admin | Aug 5, 2013 | Highlights

President and CEO of Fair Trade USA, Paul Rice, argues that increasing threats to worker safety are because businesses are forgetting their social responsibility. “Putting people back into business,” might be as (if not more) necessary as reforming legislation and mobilizing consumer support. Rice identifies three key points that business leaders should bear in mind in order to ensure sustainable business practices.

Credit-www.fastcoexist.com

Why Social Sustainability Should Be Part Of Every Business?

I can’t think of anything that illustrates the human cost of doing business more than the tragedy this past April in Bangladesh. More than 1,100 men, women, and children died when the Rana Plaza building, which housed a number of garment factories, collapsed. Most were garment workers who were ordered by supervisors to report to work, even after inspectors deemed the building unsafe.

Millions of people around the world work in dangerous and unhealthy conditions, earning a nominal income to deliver the products we consume. While the factory collapse in Bangladesh is a terrible tragedy, it’s another wake-up call that business leaders need. We can no longer ignore the human side of our global supply chains. Now is the time for all of us to recognize and embrace social sustainability–much in the same way we’ve focused on environmental sustainability for the past 20 years–as a mission-critical way of doing business. By social sustainability, I mean investing in the livelihoods of farm and factory laborers, ending worker exploitation, and ensuring that there is ethical sourcing behind the things we buy.

Some of you might be thinking that social sustainability is a phrase made up of feel-good buzz words. But social sustainability is good business.

Here are three key points that every business leader should keep top-of-mind:

SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY MITIGATES RISK

Simply put, ignoring social sustainability is a liability–to both your brand and product quality–that businesses can no longer afford.

Case in point: apparel companies, especially those that had previously outsourced their manufacturing to Bangladesh, began scrambling for PR cover within days of the Rana Plaza collapse. Earlier factory tragedies involving global corporations resurfaced as well, demonstrating the prominence of these issues in the eyes of the media and consumers.

Similarly, businesses risk product quality by ignoring the social side of sustainability. In the last month alone, the FDA issued recalls or safety alerts regarding food products tainted by salmonella, listeria and hepatitis A–contaminations that typically start in the fields where farm workers could be more vigilant if they were trained and empowered to do so. Not only do these outbreaks create a serious threat to public health, they can also cost food manufacturers millions of dollars to remedy each incidence of food-borne illness.

Investing in social sustainability allows companies to flip these types of liabilities into assets. When you provide safer working conditions, living wages, and job security, you create a more secure supply chain. When you give farm workers a reason to care about food safety and pest contamination by giving them special training and higher pay, you go a long way in ensuring the integrity of your product.

CONSUMERS WANT SOCIALLY SUSTAINABLE PRODUCTS

We’re seeing the rise of the conscious consumer–people who are informed and engaged, and who care about the environmental and social impact of the products they buy.

Businesses are responding. West Elm, for example, is partnering with Craftmark, an organization that is part of the All India Artisans and Craftworkers Welfare Association, to bring locally sourced and handmade products to consumer markets around the world. Many rug importers and exporters are looking for products free of child labor, and they work with organizations like GoodWeave for quality control. And with some companies, like prAna, customers show support by looking for the Fair Trade Certified label on their clothing offerings.

Does all this transparency pay off? Absolutely. Conscious consumers are willing to spend a little bit more to know that the items they purchase are sweatshop-free, help the lives of the workers who made them, and build stronger communities.

SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY HAS NEVER BEEN EASIER

The good news is that social sustainability has never been easier to practice. There is no lack of information, and no shortage of partners who can help you develop, implement and audit a business model that gets it right:

The Fair Labor Association conducted an in-depth investigation of factories in China operated by Foxconn, Apple’s biggest supplier. Both Apple and Foxconn have agreed to follow FLA guidelines to reduce working hours, protect pay, and improve working conditions.

United Farm Workers, Oxfam America, and Costco, in collaboration with many other organizations, have lent considerable muscle to develop and support the Equitable Food Initiative. One of the initial projects had California strawberry growers commit to training their workers and paying them higher wages as an incentive to practice a higher standard of food safety.

Green Mountain Coffee Roasters recently completed a two-year partnership with Fair Trade USA and USAID to educate small-scale coffee farmers in Brazil about environmental conservation and effective natural resource management.

By putting people back into business, we’re choosing a world where farmers and workers are able to fight poverty through better trading practices, work in safe conditions, and have access to adequate schooling, health care, and housing. When this happens on a large scale, social sustainability will no longer just be “good business,” it’ll be business as usual.

by Admin | Aug 5, 2013 | Highlights

The Rana plaza collapse in Bangladesh has raised a critical call for improvement of working conditions in developing countries. Inspired by this incident, Boston Global Forum directors decided to choose its mission of the year 2013 as “Minimal standards for Worker safety”. The issue has gathered several concerns from political leaders and renowned professors at Harvard and MIT.

Mr Vu Dang Vinh, CEO of Vietnam Report also has shown his concern and expressed support for the issue.

Photo: Professor Joseph Nye presented awards to Top Vietnam largest companies in VNR500 in 2010.

Photo: Professor Joseph Nye presented awards to Top Vietnam largest companies in VNR500 in 2010.

“Boston Global Forum has raised an important issue of worker safety which is still an absence in many international conversation. Professor John A. Quelch has proposed very interesting questions for discussion of “Minimal Standards for Worker Safety” with very unique perspective.

Vietnam Report, Vietnam Economic Forum (VEF) and VNR500 (Vietnam Top 500 largest company ranking) highly appreciate that Boston Global Forum has raised this issue as it core mission of 2013.

The proposal of “Minimal standards for worker safety” issue is indispensable for the year of 2013. Boston Global Forum should be the one who forms these safety standards and makes it become reality in every organizations, and every countries. These standards not only will bring good things to the workers, but also create a fair competition between countries and between organizations.

We believe that by gathering opinions and suggestions of experts in area of worker safety, political leaders, and distinguished professors, Boston Global Forum will be able to form the best standards for the problem, which will be the guidance for all countries and organizations.

The U.S. government, the United Nations should lead and set up requirements to deploy the standards outlined by Boston Global Forum. All big brands of the U.S should be the pioneer in applying the standards. Based on these BFG’s standards, US government should promulgate and enforce standards for textiles industry as the same as it did to agricultural products and foodstuffs (FDA). If these commodities do not pass standards, they will not be imported into the US market.

Vietnam Report will raise this issue in its upcoming Vietnam CEO Summit 2013 conference on August 23 in Ho Chi Minh City and will mobilize all organizations, especially Vietnam textile companies to support and apply these standards.”

About Vietnam Report

Vietnam Report Joint Stock Company is the pioneer and leader in areas of report, ranking for business organizations, products and services in Viet Nam. It business focused on providing consultant services, and data for marketing, investment and market research in Viet Nam. Its renowned products and services include VNR500 (Vietnam’s Top 500 largest companies), FAST500 (Vietnam’s Top fastest growth companies), V1000 (Vietnam’s Top 1000 income tax-paid companies).

by Admin | Aug 5, 2013 | News

With all eyes on Bangladesh, it’s worthwhile to take a look at safety standards in garment factories in other countries. An International Labor Organization report discloses a disappointing decline in worker safety in Cambodia.

Credit- qz.com

For international retailers who have committed more than $250 million to improve factory workers’ safety in Bangladesh, the conditions in Cambodia should give them pause.

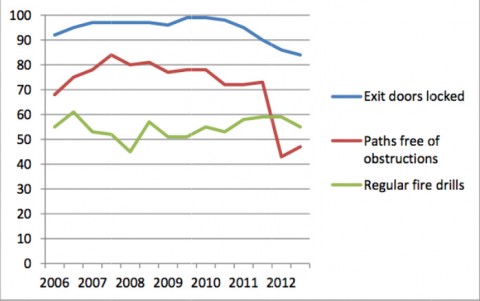

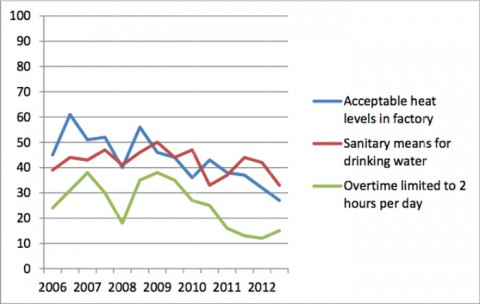

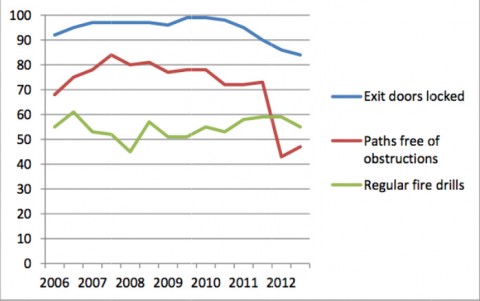

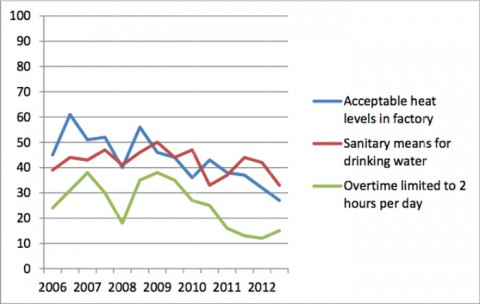

A bi-annual report (pdf) from the International Labor Organization-sponsored Better Factories program reveals a disturbing decline in working conditions in Cambodia’s garment factories. In the November 2012-April 2013 period, Better Factories found that the compliance to fire safety and worker health regulations were lower than what they were seven years ago.

Of the 155 factories assessed, 53% had obstructed access paths, compared with a little more than 30% in 2006, nearly 45% failed to conduct regular fire drills, and 15% kept emergency exit doors locked during working hours.

Credit-qz.com

The report also highlights serious violations including excessive heat levels, shortage of safety masks, lack of proper equipment for handling chemicals and inadequate access to clean drinking water.

Cambodia is among the Southeast Asian countries that have benefitted from the double-digit wage increases and shortage of factory labor in China (paywall). The number of apparel export factories in Cambodia has surged from 185 in 2001 to 412 in April 2013 (pdf). Last year, the garment industry generated over $4.6 billon in exports, accounting for 84% of Cambodia’s total exports. The garment factories employ around 2.5% of Cambodia’s 15 million citizens and remittance payments from factory workers to families in rural regions sustain about 20% of the population, according to Japan External Trade Organization (pdf).

But the industry has been marred by mishaps and labor unrest in recent months. In May, accidents at two factories, including one that left two people dead when part of a shoemaking factory collapsed, highlighted unsafe conditions. Local media pounced on instances of workers fainting because of poor air circulation, and factory owners threatening to fire employees who refused to work overtime. Workers complained that the prevalence of short-term contracts lasting three to six months made it easier for employers to fire workers who joined unions (paywall) or demanded benefits like maternity leave.

A series of strikes over pay and conditions forced the factory owners to agree to a20% wage hike effective from May. Thanks to pressure by the Cambodian government, employers raised the monthly minimum wage from $61 to $75 and boosted employee healthcare stipends by $5 per month. Unions argue that, adjusted for inflation, those wages are on par with pay levels in the year 2000.

by Admin | Jul 31, 2013 | Highlights

A report, published by the Center for American Progress earlier this month, revealed that the meager wages garment workers make, in return for long laborious working days in dangerous conditions, have further decreased over the past decade. The study, prepared by the Worker Rights Consortium, examines 15 of the world’s leading apparel-exporting countries and found that between 2001 and 2011, wages for garment workers in the majority of these countries fell making it nearly impossible for them to afford the minimum necessities of a decent life.

Credit- AP/Mahesh Kumar A

The report, entitled “Global Wage Trends for Apparel Workers,” found that the gap between prevailing wages—the wages paid in general to an average worker—and living wages for garment workers in these countries has only widened. “The most troubling news in this report is that even in countries like Bangladesh and Cambodia—where wages were the lowest and least adequate for workers’ needs—workers’ pay actually stagnated or declined over the last decade,” said Ben Hensler, author of the report and deputy director of the Worker Rights Consortium. “This finding underscores the urgent need for those with the greatest power to lift garment worker wages—not just the governments of these countries, but also the U.S. and European brands and retailers that buy the apparel these workers produce. Meaningful action must be taken to raise minimum wages, pay fairer prices to factories, and give workers the freedom to form unions and bargain collectively on their own behalf.”

In Bangladesh, the world’s second-largest apparel exporter that has come under scrutiny after a deadly factory collapse in April, workers make just 14 percent of a living wage. In the other top three exporters to the U.S., China, Vietnam, and Indonesia, workers make 36 percent, 22 percent, and 29 percent, respectively, as reported in this article.

The report examined the trends from 2001 to 2011 in real wages for apparel-sector workers in 15 of the top 21 manufacturing countries. Key findings from the study include:

- In nine countries—Bangladesh, Cambodia, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, the Philippines, and Thailand—the prevailing real wage for apparel-sector workers in 2011 was less than it was in 2001. That is, apparel-sector workers in the majority of countries studied saw their purchasing power decrease and slipped further away from receiving a living wage.

- In the six countries where real wages increased from 2001 to 2011, wage growth in two of the countries, Peru and India, was modest—less than 2 percent per year when adjusted for inflation. While wage gains for workers in Indonesia, Vietnam, and Haiti were more substantial, it would take more than 40 years for the prevailing wage rate to equal a living wage even if their recent rates of real wage growth were sustained.

- Only in China did real wages for apparel-sector workers increase at a rate that would lift workers to the point of receiving a living wage within the next decade. Not surprisingly, the industrial centers in China where workers benefited from these gains have already seen a loss of apparel production, as manufacturers have shifted their facilities, and buyers have shifted their orders, to lower-wage areas both within China and in other countries.

by Admin | Jul 31, 2013 | News

In yet another testimony to how the garment industry in Bangladesh is evading reform, Emran Hossain, writing for the Huffington Post, states that the reforms made by the Bangladesh government targeted at the garment industry “barely improve safeguards for impoverished garment-sector workers, and in some cases they undermine existing ones.” Hossain’s article elucidates the greed of garment factory owners, the weak and corrupt government and lopsided approach to reform that may favor the industry more than its workers.

Credit- Getty Images/ AFP/ Munir UZ Zaman

In the wake of the Rana Plaza building collapse that claimed 1,129 lives, the Bangladeshi government announced earlier this month that it had made dozens of amendments to national labor law in an effort to better protect workers. While those changes have been hailed in the media as pro-worker and stronger than earlier law, in reality those amendments barely improve safeguards for impoverished garment-sector workers, and in some cases they undermine existing ones.

Legal experts and labor rights activists in Bangladesh explained to The Huffington Post how a number of the amendments will ultimately benefit business interests, rather than the employees they were intended to serve.

“The greed for profit has pushed Bangladesh’s garment industry into its present, disastrous condition,” said Salim Ahsan Khan, legal counselor at The Solidarity Center, a global labor rights group. “And it’s for the same greed that we miss this opportunity to strengthen laws needed for a growing garment industry.”

For starters, the amendments do nothing to ramp up the already-weak punishments for factory owners who put their workers in danger. The Rana Plaza factory owners and managers were given the highest charge possible under the law: contravention of law with dangerous results, or failing to warn workers ahead of an accident, resulting in a loss of life (though the owners forced workers to enter the building). The punishment for one of the most deadly tragedies in Bangladesh’s history? If convicted, those responsible would be sentenced to a mere four years in prison. The recent amendments leave such modest sentencing in place.

“Punishments are there in the law to deter violators. But, unfortunately, the amendments do not deal with their weakness,” said AKM Nasim, senior legal counselor at The Solidarity Center.

It is widely believed that disasters continue to plague the garment industry because factory owners have little to fear in the way of punishment. In the case of Rana Plaza, the tragedy likely never would have happened had the owners of the building and factories not pressured workers to clock in after dangerous cracks were discovered in the structure. Over the course of the past decade, few Bangladeshi business owners have been held to account in a spate of disasters that have claimed some 6,000 lives.

The recent amendments to labor law do incorporate new building and construction codes. But legal experts say that because these provisions don’t come with serious offenses for business owners who fail to comply with the new codes, there is little incentive for them to improve their buildings. Furthermore, influential businessmen in Bangladesh have a way of avoiding such violations to begin with; government inspectors are often resistant to cite them, due to their strong influence on the government.

Several of the amendments to labor law are supposed to make it easier for workers to unionize in a country where collective bargaining is weak. Unfortunately, much of the unionization process is now left to the discretionary power of certain bureaucrats. Under the new amendments, the registrar for trade unions can deny workers the permission to unionize if the official is unsatisfied with the petition. This provision has angered workers and labor rights activists alike, given the country’s infamous history of corruption. The registrar, they worry, may end up catering to powerful businessmen and denying workers their union elections.

“The law should have been that workers cannot be prevented from unionizing once some specific requirements are met,” Nasim said. “But in addition to meeting the requirements, the law requires you to satisfy the registrar.”

Like before, the workers will need to show support of 30 percent of their colleagues in order to apply for union registration. Labor rights activists had wanted that requirement reduced to 10 percent, due to the hurdles that come with organizing a massive factory. But that proposal was turned down.

Still, workers found small victories in the changes to unionization guidelines. Owners, for instance, will no longer be supplied by the government with a list of workers seeking to unionize — a procedure that in the past had led to suspensions, firings and crackdowns on organizing efforts. The amendments also partly fulfilled workers’ demands that employees from outside factories be allowed in particular unions. Now, 10 percent of the union members in government-owned factories may come from outside the factory, although private-sector factories are carved out of this stipulation. (Government factories are almost defunct in Bangladesh. For example, almost all garment factories — the primary industry in the country — are private.)

Despite these modest benefits for workers, unionization remains illegal in government-controlled export processing zones. Even after the most recent changes, no union is allowed inside any of the official processing zones, though many of the plants that produce clothes for Western countries are located in these areas.

And the government still reserves the right to stop any demonstration or strike deemed disruptive to the community or harmful to the national interest. The historical record indicates there is little chance for change here: Since the rise of Bangladesh’s garment industry in the late 1970s, every decent-sized demonstration has been declared disruptive. Even the 2006 labor unrest — which, after decades of industrial growth, led to the formulation of the country’s minimum wage — was identified by the government as an international conspiracy to destroy the country’s garment industry.

Furthermore, the labor law amendments appear to have made it easier to dismiss workers. According to the amendments, owners can dismiss workers accused of “misconduct” without giving them severance benefits. Earlier, such a dismissal required payment. Labor rights activists fear this will now be abused by the owners, who will use the provision to target union activists.

“It will not be possible for the union leaders to work for the workers freely, since they’ll work in fear of losing their jobs,” Nasim said.

The amendments also exempt export-oriented factories from having to share 5 percent of their profits with workers, as they were previously required to do, at least in theory. Of course, Bangladesh’s primary export-oriented sector is the garment industry. Labor rights activists claim this amendment will benefit several thousand factory owners at the expense of about four million workers.

“The labor law is amended only to meet owners’ expectations,” said Nazma Akter, president of the Sammilito Garment Shramik Federation, a trade union association.

Kalpona Akter, executive director of the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity, says that another provision in the amendments sanctions the practice of outsourcing. While contracting out factory work had been loosely permitted before, now contractors who supply workers to factories will register with the government. According to Akter, the new law is a de facto encouragement of the practice.

Nasim, the lawyer, said more outsourcing will allow factory owners to dodge the responsibilities they have as workers’ direct employers. The responsibility will now instead fall to the contracted labor supplier.

Nazma and Kalpona have good reason to believe the industry will benefit more from the new amendments, rather than workers. More than a third of the lawmakers who approved the legal changes are businessmen, most of them in the garment sector. Nearly half of those lawmakers are from the ruling coalition government, and many of them were involved in bringing the amendments to pass.

A number of the most recent measures are almost comically meaningless — such as those changing the use of the word “latrine” in the earlier law. Other amendments dealt with clarifying language in previous legislation, and even corrected punctuation marks.

When contacted by HuffPost, Atiqul Islam, the president of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association, insisted that the new amendments are strong, though he said they would be a challenge for businesses to comply with.

“However, I welcome this law for the sake of our garment industry,” he said.

When asked about the shortcomings in the amendments that have been detailed by labor activists and others, Islam said he hadn’t noticed them, then cut the interview short.

“I have to take a look at it again,” he said. “I need to leave this conversation now. I am in the middle of my prayer.”

by Admin | Jul 31, 2013 | Highlights

Credit- New York Times/ Taslima Akhtar

While developed countries debate regulations and trade impositions after the Rana Plaza collapse, Bangladesh needs to independently bolster reforms surrounding the garment industry. At present, the garment industry enjoys special privileges like subsidies and tax breaks and, they pay less tax as compared to other industries. Their factories, too, are not all build on legally obtained land, sometimes with environmentally detrimental consequences. The following New York Times article, reported by Jim Yardley, has the complete story.

Garment Trade Yields Power in Bangladesh

DHAKA, Bangladesh — In the honking, congested heart of this overcrowded capital, one glass office tower stands uniquely alone, surrounded by water, accessible by a small bridge. It is a symbol of the power of Bangladesh’s garment industry, the headquarters of the country’s most powerful association of factory owners. It is also illegal.

So said the Bangladesh High Court, concluding that the land had been illegally obtained, the building had been erected without proper approvals and the location threatened a network of lakes that form the natural drainage system of the capital. The High Court called the building “a scam of abysmal proportions” and ordered it demolished within 90 days.

That was two years ago. The building still stands. The case is now in a legal limbo — more proof, according to critics, of the power of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association. Members control the engine of the national economy — garment exports to the United States and Europe. Many serve in Parliament or own television stations and newspapers.

For two decades, as Bangladesh became a garment power, now trailing only China in global clothing exports, the trade group has often seemed more like a government ministry. Known as B.G.M.E.A., the organization helps regulate and administer exports and its leaders sit on high-level government committees on labor and security issues. Industry trade groups in the United States could only imagine such a role.

But the April collapse of the illegally constructed Rana Plaza factory building, which killed more than 1,100 people, has placed the entire global supply chain that delivers clothes from Bangladeshi factories to Western consumers under scrutiny. And the quasi-official garment group, in the eyes of its critics, presents a major conflict of interest at the center of Bangladesh’s troubles and is a big part of the systemic problems that have made the country a dangerous place for garment workers.

“You can’t put the fox in charge of the chickens,” said Rizwana Hasan, an environmental lawyer. “B.G.M.E.A. has no regulatory authority under the laws of the country. It’s a clubhouse of the garment industry.”

Bangladesh is working to restore the garment industry’s credibility after last month’s decision by the Obama administration to suspend a special trade preference for the country. The European Union is also considering penalties. Bangladesh has responded by passing new labor laws and pledging to inspect the structural safety and legal compliance of the nation’s 5,000 garment factories.

In both instances, the garment group’s interests were well represented. It has hired a team of engineers and is helping oversee the post-Rana Plaza factory inspections — even as the High Court cited the group for a litany of violations on its own headquarters. Meanwhile, the trade group brought its influence to bear in a lobbying campaign as Parliament amended the labor laws this month.

Bangladeshi officials promised to overhaul their labor laws, which fall short of standards defined by the International Labor Organization and tend to suppress unions, contributing to safety problems, labor advocates say. But the results of the overhaul were less significant, especially for the garment industry. One amendment required that industries create profit-sharing programs for workers. But exporting industries, notably the garment sector, were exempted.

Restrictions on labor organizing were eased, but far from fully lifted. The new law requires that 30 percent of factory workers must sign petitions to form a union, a telling obstacle given that many factories have thousands of employees and have few places to hold meetings and organize.

“Bangladesh had a golden opportunity,” said Roy Ramesh Chandra, a labor leader, who said that the political influence of factory owners diluted some of the amendments. “The employers have tremendous influence.”

Business interests dominate Bangladesh’s Parliament. Of its 300 members, an estimated 60 percent are involved in industry or business. Analysts say 31 members, or 10 percent of the country’s national legislators, directly own garment factories, while others have indirect financial interests in the industry.

Factory owners say their political clout is vastly overstated and dismiss suggestions that they exert influence over top elected leaders, and some analysts agree their influence is sometimes overstated. But the trade group clearly is part of the process in ways that set Bangladesh apart.

Three years ago, the prime minister created an industrial police force to maintain order in factory districts and act as an independent arbiter to solve disputes between workers and management. But many workers and labor organizers say the force almost always favors owners. The trade group is even supposed to buy patrol cars for officers.

“This organization is extremely powerful,” said one senior government official, who said much of its clout comes from political contributions. “The political parties are running after money.”

The trade group was formed in 1983 as Bangladesh, then one of the world’s poorest countries, was trying to build its economy by developing a garment industry. Initially, it had no headquarters and no bank account.

“When I first went out there, the B.G.M.E.A. was run out of a garage,” said Don Brasher, who worked as a trade consultant to Bangladesh for more than a decade. “It was not institutionalized at all.”

That quickly changed. Under the rules of global textiles, developing countries faced restrictions on garment exports and, in the case of the United States, were assigned trade quotas. Managing this quota system was critical and complicated. Bangladesh’s government decided to delegate administrative tasks to the trade group — including the authority to regulate certain transactions and collect fees.

“That was pretty extraordinary,” said Mr. Brasher, who lived in Dhaka for two years and worked closely with the group on the quota system. “Ordinarily, that is done by a government agency. There’s nothing like that, anywhere. But it was done out of necessity.”

Bangladesh’s government is notoriously corrupt and has limited bureaucratic capacity to handle the intricate mechanics of global trade. Politics is ferociously contested and marred by regular nationwide strikes, known as hartals. In this environment, the group became a stabilizing force as global trade rapidly grew.

Even after the quota system expired in 2005, the trade group steadily expanded its regulatory responsibilities. Today, it enjoys a near stranglehold on exports: only factories that are among its members are allowed to export woven garments, with some exceptions. The group regulates the importation of fabric and issues certificates of origin, the required proof that a garment is made in Bangladesh. It has arbitration committees to settle disputes and administers the often-complex practice of subcontracting.

On a recent evening, Atiqul Islam, the group’s president, sat at his desk and signed applications from factory owners seeking duty-free status to import machinery. A half-hour earlier, he had presided over a news conference about a skills training program for workers that the group had organized with the United Nations Development Program, the British international development agency UK-AID and the International Labor Organization.

“Zero power,” he said while signing the tax waiver applications, flicking away a question about the group’s influence. “The government decentralized a few things to us, so we are doing them. We can do it much faster.”

Many factory owners portray the industry as a public service, providing millions of jobs. The health of the garment sector is often seen as a national security issue, with the industry accounting for 80 percent of Bangladesh’s manufacturing exports and providing critical foreign exchange. It is the trade group that maintains order in daily operations of the industry, owners say.

“Otherwise, there would be chaos,” said Annisul Huq, a former president of the trade group. “Yes, we can criticize the B.G.M.E.A. But it has a very strong role. Somebody has to lead.”

Factory owners face many challenges in Bangladesh, including high interest rates on loans. But the heroic self-image of the sector is somewhat overstated. Garment factories enjoy subsidies and tax breaks not offered to other industries, and pay less tax. A recent study in a Bengali-language newspaper estimated that these subsidies and tax breaks exceeded tax revenues from the industry by roughly $17 million.

“The doors of the treasury are open for them,” said Badiul Alam Majumdar, secretary of the nonprofit group Citizens for Good Governance. “They extract all kinds of subsidies. They influence legislation. They influence the minimum wage. And because they are powerful, they can do, or undo, almost anything, with impunity.”

One unlikely critic of the trade group is Rubana Huq, the wife of Mr. Huq, who is now the managing director of the family’s garment conglomerate, Mohammadi Group. She said the garment industry in Bangladesh has matured and must be regulated by a transparent, independent arbiter, possibly a new government ministry.

“Of course, there is a conflict of interest,” she said. “There is no reason why a body like B.G.M.E.A. would be credible with the international players.”

Ms. Huq and other critics point to the headquarters building as a symbol of its protected status. Environmentalists have long protested and argued that the building’s location on a de facto island inside a city lake impedes the natural drainage network and contributes to flooding in the capital during the monsoon.

Illegalities abounded, according to the High Court ruling: construction started before the group had won final approval on a building plan; the land transfer from a government agency violated national laws on usage of public land. Yet the group’s leaders argue that the building’s status has been validated at the highest level: two prime ministers led different inauguration ceremonies at the site.

“It is not illegal,” said Mr. Huq, his voice rising. “We have applied to the government for the land. The government has given us the land. Two prime ministers have opened it. What validation do you want?”

But Iqbal Habib, an architect who designed the plan to renew the lake system, said the group could not be exempted from rules governing others. “They are always talking about their compliance with the buyers,” he said. “What about their compliance with the laws of the country?”

For now, the case is stalled. The Supreme Court is supposed to hold a final hearing, but with elections coming, the government has shown little interest in confronting the country’s most powerful industrial bloc. It is unclear if a hearing will take place.

“It has gone to the Supreme Court,” Mr. Huq said. “That could take forever. It is Bangladesh. We have full trust — as long as they give a verdict in our favor.”

He is smiling, joking, to a degree.

Julfikar Ali Manik contributed reporting.

by Admin | Jul 25, 2013 | Highlights

Feeling the heat from international pressure, Bangladesh passed new labor laws to help improve worker rights and aid the formation of trade unions. But human rights groups say that law has only made “modest” improvements.

Source- Flickr Creative Commons/ Jankie

Steven Greenhouse from New York Times has the full article:

Under Pressure Bangladesh Adopts New Labor Law

Published: July 16, 2013- Facing intense international pressure to improve conditions for garment workers, Bangladeshi lawmakers amended the country’s labor law this week. But while the officials called the new law a landmark strengthening of workers’ protections, rights groups said the law made only modest changes and took numerous steps backward that undercut unions.

Bangladeshi lawmakers adopted the new law three weeks after the United States suspended Bangladesh’s trade preferences, saying that labor rights and safety violations were far too prevalent in that country’s factories. Moreover, the European Union has threatened to revoke Bangladesh’s trade privileges for similar reasons.

Speaking about the new law, Khandaker Mosharraf Hossain, the chairman of the parliamentary subcommittee on labor reforms, told Reuters: “The aim was to ensure workers’ rights are strengthened, and we have done that. I am hoping this will assuage global fears around this issue.”

The Bangladeshi government has faced fierce pressure to improve conditions for the nation’s four million garment workers since the Rana Plaza factory building collapsed in April, killing 1,129 workers.

Under the new law, factories will be required to set aside 5 percent of profits for a welfare fund for employees, although the law exempts export-oriented factories. Apparel is Bangladesh’s dominant industry, with $18 billion in annual exports, making it the world’s second-largest garment exporter after China.

As under the old law, workers hoping to form a union must gather signatures of 30 percent of a company’s workers — a level that was onerous, labor leaders said, because many apparel manufacturers have thousands of workers. To make unionizing easier, labor leaders were urging lawmakers to adopt a 10 percent threshold. In Bangladesh, several unions might represent employees in a single factory.

Business leaders complain that Bangladeshi unions are highly political and sometimes stage disruptive strikes as a complementary tactic to political blocs’ lobbying and infighting.

In a step that could help unionization, the new law bars the country’s labor ministry from giving factory owners the list of the 30 percent of workers who want to form a union. Labor leaders said that after receiving those lists, owners often fired union supporters or pressed many to withdraw their names from the petition, bringing the number below the requisite 30 percent mark for a union to be recognized.

Some labor leaders expressed concern that government officials would still give the names to factory owners, perhaps because of collusion or bribes.

“The government says this will make it easier for workers to organize,” said Babul Akhter, the president of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation. “That’s not true.”

Mr. Akhter praised the legislation for adding some protections on fire and building safety: it strengthens requirements for permits when a factory adds floors.

Human Rights Watch said, however, that the new law would make unionizing harder. It criticized the legislation for adding more industrial sectors, including hospitals, where workers would not be permitted to form unions. The group noted that workers in Bangladesh’s important export processing zones would remain legally unable to unionize.

In addition, the government would be empowered to stop a strike if it would cause “serious hardship to the community” or be “prejudicial to the national interest.” And workers at any factory owned by foreigners or established in collaboration with foreigners would be barred from striking during the operation’s first three years.

“The Bangladesh government desperately wants to move the spotlight away from the Rana Plaza disaster, so it’s not surprising it is now trying to show that it belatedly cares about workers’ rights,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch. “This would be good news if the new law fully met international standards, but the sad reality is that the government has consciously limited basic workers’ rights while exposing workers to continued risks and exploitation.”

Under the new law, unions would need government approval before they could receive technical, health, safety or financial support from other countries.

An Obama administration official said various agencies were seeking to obtain the exact language of the new law in order to study it.

Roy Ramesh Chandra, a powerful Bangladeshi labor leader, said the legislation might not have done enough to persuade Europe not to suspend trade preferences or to get Washington to reinstate such preferences.

Jim Yardley contributed reporting.

by Admin | Jul 26, 2013 | Highlights

Boston Global Forum brings together leaders and renowned professors from Harvard and MIT to lead the discussion on worker safety.

Professor Richard Locke (far right) addresses the group as Governor Michael Dukakis (center) and Professor Thomas Kochan listen on.

July 18, 2013 Boston- To propel discussions around Boston Global Forum’s (BGF) 2013’s ‘Issue of the Year’, a group comprising BGF Chairman Michael Dukakis, BGF Executive Director, Nguyen Anh Tuan, distinguished academicians from universities like Harvard and MIT, and representatives from non-profit advocacy groups met last week in Boston to discuss Minimal Standards for Worker Safety . The infamous Rana factory collapse in Bangladesh that killed over 1100 people in April 2013 is the inspiration behind BGF’s Mission for 2013.

Evoking the genesis of Boston Global Forum and its choice of mission for 2013, Governor Dukakis opened the meeting by reminding its participants that BGF was created to reach out to the entire world using information technology to initiate a global conversation around of the issue of the year. This conversation, unlike most others, would be solution-oriented– one that results in a set of recommendations that could be “internationally enforced”. He further added that there was a stark absence of international conversation around the issue of occupational safety, and hoped that the forum could leverage a dialogue “in a way that could build a body of law that is enforceable.”

The meeting addressed several aspects of international worker safety drawing upon examples of supply chain policies, private and public sector arrangements and trade agreements. Richard Locke, professor of Political Science at Brown University and author of The Promise & Limits of Private Power stated that the best success stories, in his understanding of the processes, lie in the combination of private and public sector interventions. While private enterprises are necessary to ensure efficiency (in keeping with their best interest), the government needs to enforce basic enabling rights for workers. “Where you see that combination, that’s where you see success, “ adds Locke. He illustrated his theory with the Better Work Cambodia Program directed by the International Labor Organization (ILO). In this program, the United States used its markets as a “carrot” to drive improvements in working conditions and safety standards. The resulting improvement in worker safety which was made possible by the combined efforts of local governments, private business and the ILO.

The round-table, comprised of American luminaries, rebuked the response of American multinationals to the Bangladesh tragedy. “We’ve got to take advantage of putting pressure on the multinationals and the US multinationals have been slow relative to the Europeans,” said Thomas Kochan, Co-Director MIT Sloan Institute for Work and Employment Research. While European multinationals are putting pressure to change labor law in Bangladesh after the tragedy, American corporations like Walmart and Gap, are withholding involvement with trade unions on the ground or international alliances, he said. Jeffrey Stookey, former professor at Boston University augmented this idea by pointing out that European Union stopped bank loans to Bangladeshi companies that fell short of safety standards. John Quelch, professor at Havard Business School also pointed out that the US has failed in stepping up to this challenge- a behavior that is inconsistent with its reputation of a country that pioneered positive global interventions in the 20th century.

Harvard Business School Professor, John Quelch (left) talks to MIT professors Richard Locke (center) and Thomas Kochan (right).

The Rana Plaza factory collapse draws emphasis to the need to talk about a subject that hasn’t received enough attention. Quelch recalled his experience leading a business school in China to talk about the “less-than pleasant practices” that workers have to endure. He hoped that the Bangladesh tragedy could work as a “catalyst” to stimulate discussions on an often-overlooked issue. Professor Quelch went on to emphasize the need for legislation in bringing about any stringent change in worker safety. “Even with legislation, it’s often difficult to make things stick as well but without it I feel that, personally, it’s going be tough to keep the interest and momentum up,” he said. While addressing human rights concerns, Quelch pointed out that children have, unfortunately, been left out of conversations surrounding the Bangladesh disaster. Rendered helpless by their vulnerability, children are often the worst victims of disasters and calamities.

Incidents like the Bangladesh disaster cannot be averted by enforcing legislation alone. MIT’s Thomas Kochan argued about the need for a bottom-up approach in addressing this subject. He stated that sustained enforcement of labor law could be achieved through the development of local institutions like trade unions, NGOs and coalitions resulting between them.

State laws within the US have attempted to ensure transparency and labor standards in procurement processes, sometimes with success. Liana Fozvog from International Labor Rights Forum (ILRF) and Marcy Gelb from MassCOSH (Massachusetts Coalition for Occupational Safety and Health) described their findings stating that several states and cities across the country have joined a sweat-free consortium that should ideally be instituted at the federal level. In Massachusetts, laws that require disclosure of factories and apparel to be union-made are not always upheld.

Moving Forward

The meeting culminated in dialogue about future actions for Boston Global Forum. Recommendations included a ten-point plan for the Commonwealth to help position Massachusetts as a ‘best practice state’ in the field of worker safety; networking to encourage American multinational companies to participate in future meetings on compensating victims of the Bangladesh disaster; bringing together various stakeholders and actors to talk about solutions that have worked and about governments, private institutions and other organizations that are making a difference; transforming the Boston Global Forum website into an information resource for interested audiences; garnering interest and representation from the State Department or the Department of Labor in BGF’s discussions; inviting Human Rights and Business expert Michael Posner, professor at New York University’s Stern’s School of Business and former official at the State Department to join the forum; and addressing local state laws in Massachusetts that are not being effectively enforced.

by Admin | Jul 23, 2013 | Highlights

Time Magazine’s online news portal reports on a significant reduction in the number of people living in poverty in Bangladesh. According to the article, The World Bank announced that number of people living in poverty dropped from 63 million in 2000 to 47 million in 2010. The proportion of the population living below the poverty threshold — also known as ‘poverty rate’- was reduced to 26 percent from 29.5 percent.

Source- Flickr Creative Commons/ DFID UK

These under-reported figures deserve a noteworthy mention for a country that is plagued by poverty, natural calamities and infrastructural breakdown.

Click here to read the complete article.