by Admin | Sep 13, 2013 | Highlights

In the wake of the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse, which killed more than 1,100 Bangladeshi garment workers, a group of retailers formed a pact to prevent future disasters. Some firms hesitated to sign the legally binding contract, fearing litigation. The labor unions and European firms which created the pact were concerned about the lack of cooperation and the implications for reform in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh Fire and Safety Accord

On July 8, 2013, over 80 global retailers, mainly European, and two labor unions proposed a five- year plan to improve working conditions in Bangladesh garment factories called the “Bangladesh Fire and Safety Accord”(BFSA).

1.Features of the pact included:

- Independent inspections of factories, with safety violations made public on the Internet

- Retailers to underwrite mandatory repairs and building improvements at factories

- Fire and building safety training to be given by trade unions

- Trade unions to have a seat on the Accord’s governing board

- Legally binding arbitration for non-compliance, led by the Accord’s steering committee

The pact required inspection of factories working for the signatories over two years

2. During that period, signatories of the Accord agreed to maintain production in Bangladesh. Participating retailers would share information about the factories they used, and each of those factories would be inspected within nine months.

3. Factories found to be unsafe would close for repairs, and workers would be paid up to six months’ salary during that time.

4. The cost of implementation would be split according to the proportion of production each brand had in Bangladesh – with a maximum outlay per retailer of $2.5 million over five years.

5. If a retailer failed to provide funding, or continued production in unsafe factories, the signatories could file complaints. A committee composed of three labor group representatives, three brand representatives and one member from the International Labour Organization (ILO) would enforce the Accord’s terms.

6. Disputes would be referred to arbitration, as needed, and the outcome would be legally binding in the brand’s home country. No penalty provisions were included in the pact.

For full article please download PDF file Rana Plaza (B)

by Admin | Sep 13, 2013 | Highlights

On April 24, 2013 the Rana Plaza factory building collapsed in the Savar industrial district outside of Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. Over 1,100 people were killed in the worst industrial accident since over 2,000 people were killed (and 150,000 injured) in the Union Carbide plant gas leak in Bhopal, India. Most of the victims worked for the five garment factories housed in Rana Plaza, whose primary clients were European, US and Canadian firms. Export contracts to such firms had helped Bangladesh become the world’s second largest clothing exporter. Rana Plaza was not the first tragedy to occur in Bangladesh’s garment industry, and without intervention, more might follow. Following the Rana Plaza disaster, international brand owners, domestic and foreign governments, labor unions and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), began to discuss responsibilities for improving conditions for Bangladeshi garment workers.

The Bangladesh Garment Industry

Following independence from Pakistan in 1971, the Bangladesh government began privatizing industries to spur economic growth. The garment industry became a major force in Bangladesh after the Multi-Fiber Arrangement (MFA) was enacted in 1974. The MFA regulated the sale of garments and textiles from developing countries to first world countries. The MFA, which was in effect until 2004, imposed quotas on garment exports from Korea, China, Hong Kong and India. No quotas were imposed on Bangladesh’s garment exports and its industry grew from $12,000 worth of exports in 1978 to over $21 billion in 2012. Even after the MFA expired, Bangladesh maintained export volume, thanks to its low labor costs. In 2012, Bangladesh was the second largest garment exporter in the world, after China.

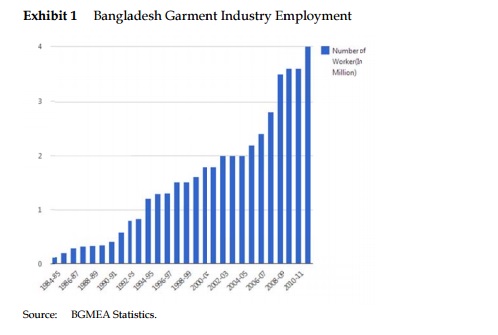

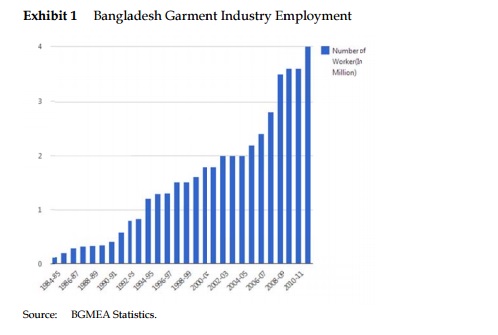

The garment industry was a major force in the Bangladesh economy. The industry employed 3.6 million people (and an additional million, through indirect employment) or roughly 2% of the population.6 The garment industry accounted for 13% of GDP. It was the single largest source of exports, 78% in 2011. (See Exhibit 1 for growth in garment industry employment over time). Workers in garment factories were paid approximately 13% more than workers in other industries. The vast majority of garment workers were women. In 2011, around 12% of Bangladeshi women between 15 and 30 years of age were employed in the garment industry.

Global Customers

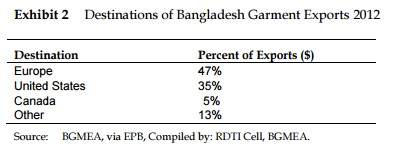

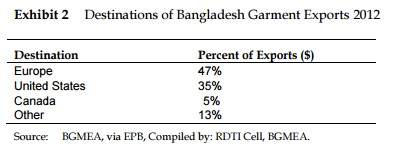

The majority of garments produced in Bangladesh were exported. In 2013, 2,000 out of 5,000 garment factories had export contracts, with many of the remaining 3,000 factories working as sub- contractors that provided additional capacity for the factories with international orders.11 Some multinational brands imposed strict limitations on the use of sub-contractors in their contracts ith primary suppliers, (in certain cases, processes existed for MNCs to grant permission for use of sub- contractors). It was also common for brands to employ agents to locate production capacity on their behalf. Nearly 90% of garments produced in Bangladesh were exported to the United States, Europe and Canada (see Exhibit 2 for proportionate export volume). In 2012, the US alone received $4.9 billion worth of garment exports from Bangladesh.

Many US and European fashion brands sourced items from Bangladesh. Brands with operations in Bangladesh included well-known global fast fashion labels H&M, Inditex (Zara), and Loblaw’s (Joe Fresh); as well as other low-to-mid priced labels like Wal-Mart, Gap, and PVH (Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger, Timberland). Many brands required garment production to align with the seasonal release of new clothing collections (in spring, summer, fall and winter). These production schedules caused large spikes in demand for capacity, with little room for errors, around the seasonal release dates, and lower demand at other times.

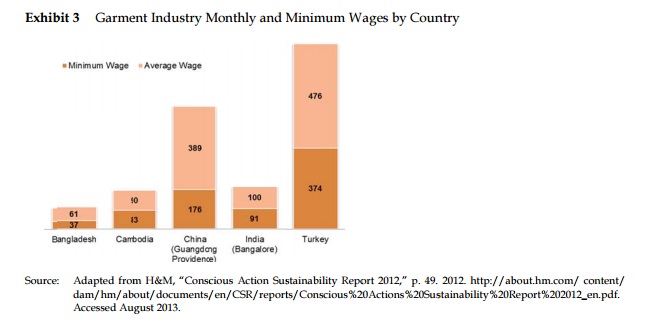

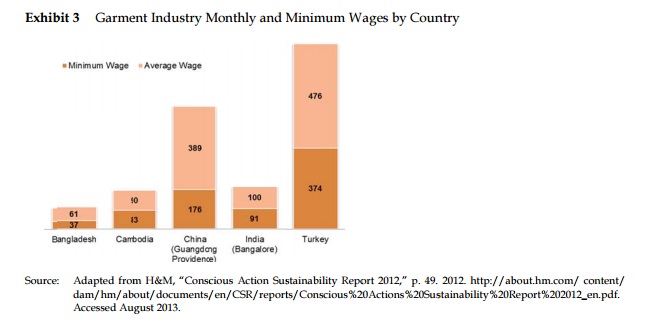

Low cost production and large capacity were key incentives for multinational corporations (MNCs) to produce garments in Bangladesh. The minimum wage in 2012 was $37 per month, and had only increased by $29 over the past 30 years. In comparison, China, the largest clothing exporter, had a minimum wage four times that of Bangladesh, and saw its labor costs increase by 30% in 2011 alone. As shown in Exhibit 3, Bangladesh’s minimum and average wages were far lower than those of other developing countries which produced garments for export. Combined labor cost differentials were expected to help Bangladesh’s garment industry to reach $30 billion by 2015.

Factory Conditions

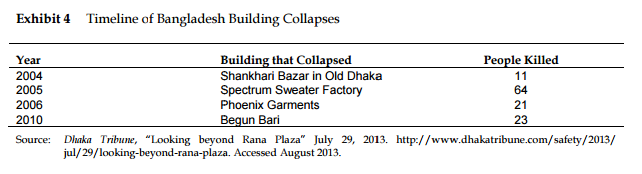

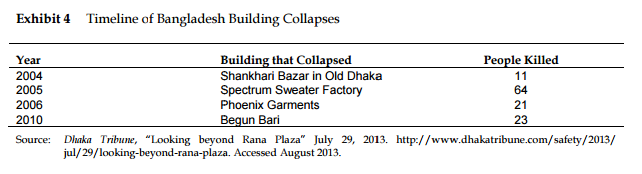

More than 1,000 garment workers were thought to have died and 3,000 to have been injured working in Bangladesh’s garment industry since 1990. (See Exhibit 4 for a list of industrial buildings which had collapsed in Bangladesh). The quick growth of the garment industry had resulted in fast construction of factories, often at the expense of adhering to building codes. The government feared foreign investment and export contracts would flow to other low cost garment producing countries if MNCs perceived Bangladesh’s factory safety record and labor disputes as risks to their brands. In 2012, the US Ambassador to Bangladesh shared with the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) details of a call he received from the U.S. CEO of one of Bangladesh’s largest garment export customers. The CEO stated his concern that “the tarnishing of the Bangladesh brand may be putting our company’s reputation at risk.”

The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) claimed to regularly monitor member factories for safety compliance. However, it was unclear the extent to which compliance was enforced. Following the Tazreen garment factory fire caused by unsafe storage of flammable materials in November of 2012, which killed over 100 workers, BGMEA inspectors were sent to member factories to check labor and safety compliance. Four of the buildings inspected, belonging to BGMEA President Atiqul Islam, were found to have numerous violations.

Numerous NGOs sought to improve labor and safety conditions for Bangladesh’s garment workers. Care Bangladesh partnered with MNCs to create programs to help female garment workers develop leadership skills. The Global Women’s Economic Empowerment Initiative, a partnership between Care Bangladesh and Wal-mart, helped nearly 24,000 female garment workers learn their legal rights and develop communication skills. Gap worked with Care Bangladesh to form the Personal Advancement and Career Enhancement Initiative for around 500 female garment workers employed in Gap’s supplier factories. Other NGOs, like the Awaj Foundation, empowered garment workers to understand and act upon their legal rights. The Awaj Foundation’s network included 255,719 garment workers and offered programs for workers on Bangladesh labor laws, fire safety, and health care services, among others. The Worker Rights Consortium inspected Bangladesh garment factories for labor violations but, over three years, it had only checked the factories associated with three factory owners. In 2007, the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity, (an affiliate of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations,) petitioned the U.S. government to suspend trade privileges for Bangladesh, in light of worker rights violations in the garment industry.

The Bangladesh government tried to suppress activities by labor unions and other groups who attempted to highlight poor safety conditions in the country’s garment factories. Bangladesh police and security forces were suspected in the 2010 murder of labor activist Aminul Islam, the president of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation’s in Savar and organizer of the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity labor rights group. He was detained and beaten by Bangladesh security forces and his body showed signs of torture after being recovered in 2012.

Rana Plaza

On April 23, the day before the building collapse, workers observed cracks in the walls of the Rana Plaza building. The building housed five garment factories; as well as a bank and shopping mall. That morning, an engineer who had previously consulted for Sohel Rana, the building owner, deemed the building unsafe and recommended that the workers be evacuated. Later that day, a local government official met with Sohel Rana. After the meeting, the official declared the building was safe, pending another inspection. The workers of the Brac Bank branch heeded the advice of the engineer and vacated the building. Garment workers were informed that they were expected to return to work in the building the next morning, to fulfill overdue orders, or risk losing their jobs.

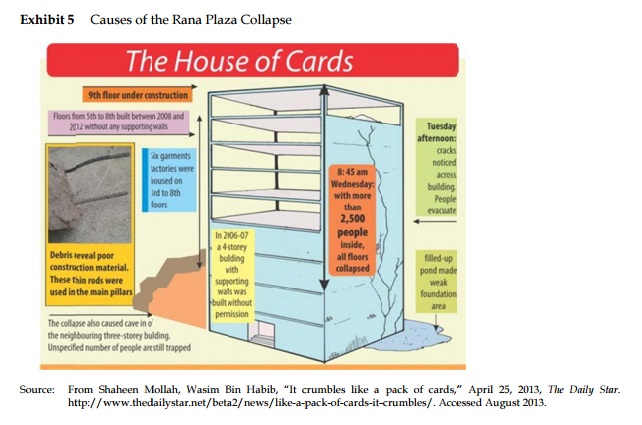

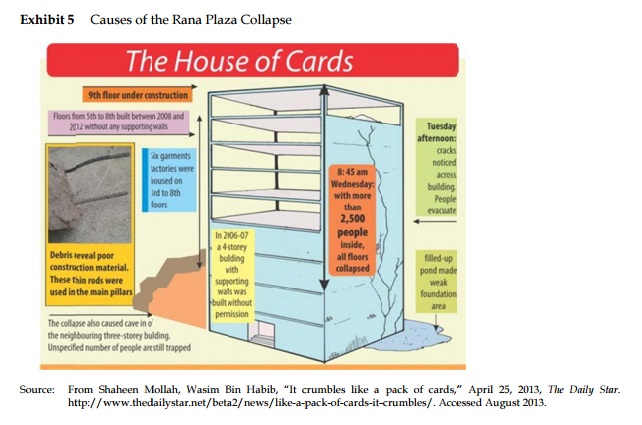

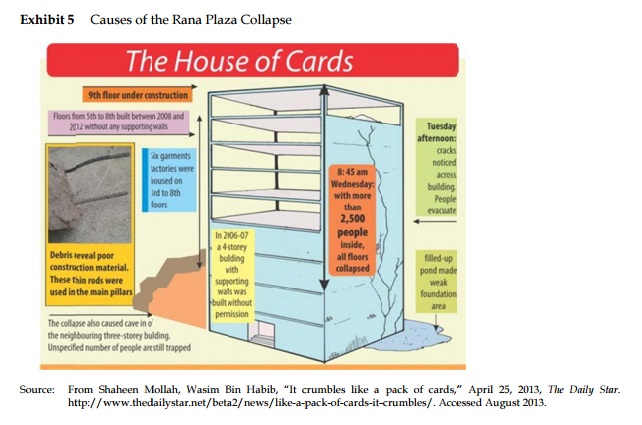

On April 24, 2013, the nine story Rana Plaza building collapsed, killing 1,100 workers and injuring 2,500 more. Sohel Rana was in his office in Rana Plaza when the disaster occurred; he fled but was arrested later at the Indian border. The disaster was caused by numerous structural problems (see Exhibit 5 for an illustration of the building):

- Four additional floors were constructed illegally upon the existing four stories, with a ninth floor under construction.

- The building lacked the supporting walls needed to hold heavy industrial machines and generators used by the factories.

- The lot where Rana Plaza stood was formerly a pond, which was filled only with sand.

- Inferior building materials were used to construct Rana Plaza.

To read the full Article please download Rana Plaza (A)

by Admin | Sep 11, 2013 | Highlights

This is a series of videos used to train managers in China to address labor disputes. Credit owed to Professor Arnold Zack of the Harvard Law School and Professor Tom Kochan of the MIT Sloan School of Management.

1) What Chinese Managers Need to Know and Do: Lessons from Richard Locke’s Global Supply Chain Research

2) Essentials of an Effective Mediation System for Workplace Disputes in China

by Admin | Sep 11, 2013 | News

Co-Founder, Chairman of The Board of Directors and Board of Thinkers, The Boston Global Forum.

Co-Founder, Chairman of The Board of Directors and Board of Thinkers, The Boston Global Forum.

Michael Stanley Dukakis was born in Brookline, Massachusetts to Greek immigrant parents. He attended Swarthmore College and Harvard Law School and served in the United States Army from 1955-1957, sixteen months of which was with the support group to the U.S. delegation to the Military Armistice Commission in Korea.

He served eight years as a member of the Massachusetts legislature and was elected governor of Massachusetts three times. He was the Democratic nominee for the presidency in 1988.

Since 1991 he has been a distinguished professor of political science at Northeastern University in Boston, and since 1996 visiting professor of public policy during the winter quarter at UCLA in Los Angeles. He is chairman of Boston Global Forum.

He is married to the former Kitty Dickson. They have three children—John, Andrea and Kara—and eight grandchildren.

by Admin | Sep 11, 2013 | News

Robert Kuttner is Meyer and Ida Kirstein Professor at Brandeis University’s

Robert Kuttner is Meyer and Ida Kirstein Professor at Brandeis University’s

Heller School. He is co-founder and co-editor of The American Prospect magazine,

and a senior fellow at the think-tank Demos. He was a longtime columnist for

BusinessWeek, and continues to write columns for The Boston Globe, Huffington

Post, and Reuters. He was a founder of the Economic Policy Institute and serves

on its board.

Kuttner is author of ten books, including the just published Debtors’ Prison and the

2008 New York Times bestseller, Obama’s Challenge: American’s Economic Crisis

and the Power of a Transformative Presidency. His best-known earlier book is

Everything for Sale: the Virtues and Limits of Markets (1997).

His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, New York Review of Books, The Atlantic,

The New Republic, Foreign Affairs, Harvard Business Review, The New York Times

Magazine and Book Review, New Statesman, Dissent, Politico, Columbia Journalism

Review and Political Science Quarterly. He has contributed major articles to The New

England Journal of Medicine as a national policy correspondent.

Kuttner’s other positions have included national staff writer and columnist on The

Washington Post, chief investigator of the U.S. Senate Banking Committee, and

economics editor of The New Republic.

He is the two-time winner of the Sidney Hillman Journalism Award, the John

Hancock Award for Business and Financial Writing, the Jack London Award for

Labor Writing, and the Paul Hoffman Award of the United Nations Development

Program for his lifetime work on social justice and economic efficiency. He has

been a Guggenheim Fellow, Woodrow Wilson Fellow, German Marshall Fund

Fellow, and John F. Kennedy Fellow.

Robert Kuttner was educated at Oberlin College, The London School of

Economics, and the University of California at Berkeley. He has taught at

Brandeis, Boston University, the University of Massachusetts, Harvard’s Institute

of Politics, and the University of Oregon. He lives in Boston with his wife, Joan

Fitzgerald, dean of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern.

by Admin | Sep 11, 2013 | Highlights

Boston Global Forum (BGF) had an opportunity to speak with Arnold Zack, an Arbitrator and Mediator of over 5,000 Labor Management Disputes since 1957; former President of the Asian Development Bank Administrative Tribunal; designer of employment dispute resolution systems;; occasional consultant for the governments of the United States (Department of State, Peace Corps, Department of Labor, Department of Commerce), Australia, Cambodia, Greece, Israel, Italy, Philippines, and South Africa, as well as the International Labor Organization, International Monetary Fund, Inter-American Development Bank, and UN Development Program. He has also been a Member of Four Presidential Emergency Boards (chair of two). (Harvard Law School), and currently teaches at the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School.

BGF: Can you tell me about your background and the works you have been involved with?

Arnold Zack: I am a lawyer, a mediator and arbitrator and I have helped design dispute resolution machinery in countries including South Africa, Bermuda, Ukraine, and many other countries. In 2005, I became interested in what is happening in China. Currently, I am involved with MIT developing a project in China to train the next cadre of graduates at affiliated business schools to have a sensitivity of work place problems. I am also mostly interested in educating these graduates to be able to design machinery that can help avoid problems like the suicides at Foxconn, and which leads to tens of thousands of strikes in China each year.

Right now, I divide my time between arbitrating for corporations like AT&T and American Airlines and the project in China. I am primarily interested in helping workers live in better conditions, make more money, and lead better lives. Obviously, there has to be a balance between these issues and the legitimate claims of employers making money and having responsibilities to stockholders. Of course, the question is what a fair balance should be. However, I am less interested in figuring out where this balances lies than in developing machinery and procedure so people can negotiate and talk about those problems. Especially, I would like to enable workers the ability to feel empowered enough to peacefully resolve disputes, so that they do not have to go on strikes, get beaten, thrown into jails and lose their jobs. You have to note that there is no prescribed level as which there is an economic balance between workers and management. In fact, there are international standards and norms, but, so far, there is no legislation that mandates worldwide employers to abide by these standards.

In any cases, I hope that I can create enough public pressure and stress the self-interests of related parties to realize the benefits of developing procedures to negotiate their differences. I think the only pragmatic approach to achieve my goal is by focusing on the self-interests and to try to establish fair procedures. We have accomplished this in the US in the union management field through the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. I have been able to accomplish this task within the U.S for individual employment disputes, outside of collective bargaining. The Arbitration Act of 1925 has been used by employers to require a commitment, by new employees that, as an employment condition, they go to arbitration mandated by the employer over any employment disputes and give up their rights to appeal to court for enforcement of statutory rights. The Supreme Court case of Gilmer vs. Interstate/Johnson Lane in 1991 endorsed such mandatory arbitration. In this case, an employee, who was hired as a stockbroker, got fired at the age of 42 or so. He tried to sue the employer based on the Age Discrimination Act, but failed, as, upon signing the employment agreement, he had given up up his rights to go to court and was forced to go through an arbitration process. I believed this process was not entirely fair and we had to have a fair procedure, so I brought to the table all related parties—the management, the union, worker groups, the American Civil Liberties Union the American Bar Association, and American Arbitration Association and established a standard procedure of fairness, called “Due Process Protocol.”

I have been trying to replicate this internationally, and I had some success in developing a similar procedure in South Africa after black workers refused to join unions controlled by white workers when allowed to in 1982. The black workers organized and white employers realized it was to their benefit to negotiate with them to resolve their disputes. We developed procedures to train mutually acceptable mediators and arbitrators and make them available to disputants to minimize strikes and establish workplace procedures for negotiation. This became the model for the development of the new constitution where the partnership of worker unions, employers and the academics established a partnership to assure resolution of political conflict. That procedure has worked well until recently when it seems to have fallen apart.

BGF: You mentioned the self-interest of related parties, can you elaborate on this point—how does this relate to your efforts and how can this help address issues including the tragedy in Bangladesh?

Arnold Zack: We accept in the US that there will be a level playing fleld in which management and the designated representative of its workers will be able to meet an negotiate the resolution of their disputes over wages hours and working conditions. That is also what happened with the development of the labor law in South Africa. But the problem as it arises in an individual country is different when one focuses on the global economy, where brands and employers seek locations where they can best enhance their profit as they make their products for the global market place. With a competitive market on price, they can best maximize their profit by paying the lowest wages to workers and having them work the longest hours, particularly if the host government turns its head, accepts bribes to avoid enforcement of their national labor laws and keeps workers from organizing into a single voice to express their demands.

The concept of employees having freedom of association and the right to engage in collective bargaining is one which is enshrined not only in the UN Human Rights Charter, it is also an international norm established by the Conventions of the ILO. In our global economy, the quest of employers seeking to produce their products at the lowest possible cost to enhance their profits, has too often led them to South East Asia where workers receive the lowest wages, and have the least protection from their own national governments. What transpired in Bangladesh with its garment factory fires is just the most recent example of the extent of such exploitation despite the availability of international norms trying to establish workplace fairness. As noted earlier the ILO establishes norms, but most nations do not enforce them within their own laws and too many countries are so corrupt that they disregard the safety as well as the workplace rights of their citizens to pocket a little more money from the contracting factory owners. The world has tended to rely on the brands to monitor these factories, although the evidence increasingly shows they cant or wont do that, turning a blind eye to the corruption and worker exploitation. There is one example to the contrary, however, Cambodia, where the ILO Itself does the monitoring, and where a separate organization the Arbitration Council provides mutually acceptable arbitrators to resolve disputes over whether there has been conformity to contract and law seeking to achieve compliance with ILO conventions. . The experience there since 2002 has lead to an expansion of the garment factories, a spread of the system to construction and tourist industries, an increase in the number of unionized employees as part of an expanding work force, and all with a notable decrease in strikes and work stoppages.. Unfortunately the Cambodian experiment has not been widely replicated because of the cost involved, but it is a beacon of what can be done with international will, national cooperation and open mindedness by the employers recognizing that they do better, and make more money when their operations are conducted smoothly without strike interruption and with machinery in place to forestall workplace disruption

Going back to our China story, the self-interest of the workers is to have fair working conditions. In the Foxconn case, a worker committed suicide because she was begging for a couple of days off to go see her brother but such leave was not approved. That case was just one of a dozen suicides. Thus, you see how the workers’ self-interest is simply being able to express themselves through a process of negotiation with the management. The United Nations Human Rights Convention gives workers the right to freely associate and to bargain collectively with management on their working conditions, wages, etc., so the workers should really have the right to get to a negotiation table and talk to their employers.IT is only logical that they strike when they are denied that basic human right. On the other hand, the self-interest of brands like Apple, Nike and Honda is to produce their products on time and sell them overseas without interruption in the workplace. Let’s take Apple, for example. Apple does not want their stockholders to say that they mistreat workers and then to decide not to invest in the company. Apple has an impact on Foxconn, but it’s also in the self-interest of the contractors like Foxconn to balance their desire for maximized profits against maintaining Apples confidence and contracts. Since , if Apple pulls out of China, Foxconn would go bankrupt. Besides, it’s also in the self-interest of the Chinese governments that these brands stay in the country to provide work and income for the Chinese citizens.

Thus, what I do now is basically to go around the world and tell these parties that it is in their self-interests to provide fair working conditions. When I was in Shanghai to speak with the American Chamber of Commerce there, plant managers asked how we could stop these strikes, and I told them that you could control these strikes by listening to and negotiating with the leaders speaking on behalf of the workers. They responded saying that the law did not require them to do so. In fact, even though China is a collective society, there is no room for workers to select their own unions or union leaders, The officially recognized unions are those organized by the ACTFU (All-China Federation of Trade Unions). Thus, the problem arises when workers believe the ACTFU does not represent them. Despite having legal and contractual rights as individuals, workers, when they unite and start demanding improved conditions, higher wages and the like, do not have any established vehicles or laws that require employers to sit down and talk to them, even though the ILO (International Labor Organization) Conventions of 87 and 98 state that workers have to rights to organize into unions and the right to bargain collectively with their employers.

Let’s look at an example of what has been happening in China to gauge the power of these spontaneous strikes of workers organizing collectively. In 2010, when Honda workers went on strike and demanded a 30% increase in their payroll, the managers compromised and gave them 20%. After that, they went back on strike again and got the remaining 10% they demanded. In most parts of the world, workers have peaceful rights to organize themselves and employers have the obligations to start negotiating. Only when this procedure fails do the employees then go on strike to exercise power to get the employer to change its position. In China and Vietnam however, it actually works backwards, the workers have to go on strike first to demand the employers to come to the table so they can talk to employers. This is the reason why I am collaborating with the business schools in China to install into the existing curricula crucial topics including negotiation, ethical standard of labor conditions and fair procedures. In addition, we’re also successful in getting a local university to establish an independent center to educate workers on topics such as peaceful resolution and the economics of running a business, as an average worker may not understand the economics of overhead, profit margin, wages, and etc.

Besides, it is also understandable why China would be skeptical of some procedures which would give workers the right to elect their own leaders, as the fall of the Soviet Union is often traced to the Solidarity Movement in Gdansk Poland where Lech Walensa led the establishment of a real trade union insisting on the right of workers to negotiate with their employer in that case the government owned ship yards. At the moment, the Chinese government does not allow workers to form their own unions. However, I believe the risk of losing foreign direct investments would outweigh the risk of opening the door for more democratic procedures at the workplace. Also, the government, so far, has not done anything to restrict us from entering the country. I am also trying to convince them that this is a practical method to resolve the problems of wildcat strikes, managers being taken hostage and other examples of frustrated workers seeking to gain a seat at the table to discuss their working conditions with management. I believe it is also in the self interest of the ACFTU to shift its role from one of monitoring the workplace to a role of representing the workers in peaceful negotiations with their employers.

This is not complex science; it is merely recognition that all the players in the economy have priorities of self interest and achieving “more” as they define that term even if at the expense of other players in their arena. But when the power is so lopsided that some of the players are excluded, or worse exploited, society owes it to all those involved to assure some measure of equity and fairness. In the world of factory work the world standard has been to permit employees if they so choose to band together as an entity that is more compatible to the power of the employer, and that standard as proclaimed by THE UN Charter and ILO conventions has been to encourage peaceful negotiations between the two parties as a better alternative to exploitation and workplace disruption through strikes. All I have been trying to do in the US and abroad is to encourage the parties to recognize that their self interest is best satisfied by recognizing that the other side likewise has self interests and that negotiations is the most rational means of resolving their conflicts. To the extent that I get people to listen to me, that is a satisfying reward. To the extent that they ask me to help them develop procedures to cope with these problems it is a reward not only for me but for the parties and society as a whole.

by Admin | Sep 11, 2013 | News

|

Name |

Title |

| 1 |

Ali E. Adiguze |

President and COO, HeidelbergCement Trading Group, Turkey |

| 2 |

Henrik G. Andersin |

Chairman

Evli Bank PLC, Finland |

| 3 |

Kalpona Akter |

Executive Director of the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity |

| 4 |

Nazmar Akter |

General Secretary & Executive Director

Awaj Foundation |

| 5 |

Syed Zain Al-Mahmood |

Correspondent, The Wall Street Journal, Bangladesh |

| 6 |

Syed Anwar |

Dhaka University |

| 7 |

Judit Arenas |

Director, Communication & Public Affairs

Deputy Permanent Observer to the United Nations, IDLO |

| 8 |

Michael Arretz |

Managing Director of Quality, CSR, and Communications

KiK Textilien |

| 9 |

Anis Asghar |

Managing Director

RDS Capital Ltd. , London , |

| 10 |

Sarah Altschuller |

Associate

Foley Hoag LLP |

| 11 |

Lutfe Ayub |

Chairman, Rabab Group

Independent Director of Alliance Holdings Ltd |

| 12 |

Srinivasa Reddy Baki |

Director ILO Country Office for Bangladesh |

| 13 |

Maren Barthel |

Manager Corporate Responsibility – Buying Markets

Otto International |

| 14 |

Chuck Bell |

Programs Director

Consumers Union |

| 15 |

Sarah Biller |

President, Capital Market Exchange |

| 16 |

James Borton |

journalist , contributor

Foreign Policy |

| 17 |

Jonas Brunschwig |

Assistant to Editor-in-Chief, Boston Global Forum |

| 18 |

Duc Lai Bui |

Assistant to Chairman of Vietnam National Assembly |

| 19 |

Phuong Lan Bui |

Deputy Director, Vietnam Institute of Americas Studies, Vietnam Academy of Social Studies. |

| 20 |

Aleix Gonzales Busquets |

Senior CSR and Supply Chain Manager

Inditex |

| 21 |

Doug Cahn |

President

The Cahn Group LLC |

| 22 |

Marcos G. Caldas |

IT Director

Lojas Marisa S/A, Brasil |

| 23 |

Wallaya Chirathivat |

Executive President

Central Retail Corporation Ltd., Thailand |

| 24 |

Swee Yeok Chu |

CEO

EDB Investments Pte Ltd (EDBI)

Ex-CEO of Bio*One Capital Pte Ltd, Singapore |

| 25 |

David Christiani |

Professor at Harvard School of Public Health

Director, Harvard Education and Research Center for Occupational Safety and Health |

| 26 |

Victor Ciuccio |

Strategic Advisor

Laborvoices |

| 27 |

Joshua Cooper |

Director / Lecturer at Hawai’i Institute for Human Rights / University of Hawai’i |

| 28 |

Jeff Crosby |

President

the North Shore Labor Council |

| 29 |

Rick Darling |

President LF USA |

| 30 |

Ramu Damudaran |

Director of Academic Impact

UN |

| 31 |

Gerben De Jong |

Dutch Ambassador to Bangladesh |

| 32 |

Nancy Donaldson |

Director

ILO-washington |

| 33 |

Chaovalit Ekabut |

President

Siam Cement Group, Thailand |

| 34 |

Abdul Hanan B. Alang Endut |

Director, Ministry of Finance(Malaysia), Malaysia |

| 35 |

Patricia Estany |

Executive Director

JP Morgan International , Spain |

| 36 |

Marcel Fratzscher |

President

German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) |

| 37 |

Nigel Freer |

Chairman

Dawson, London |

| 38 |

Takashi Fujino |

Managing Executive Officer, Manager of President’s Office

Asahi Glass company |

| 39 |

Manuel Gari |

Managing Director

Nomura, Barcelona |

| 40 |

Adam Gibbs |

Public Relations at Sunshine Sachs |

| 41 |

Marcy Goldstein-Gelb |

Executive Director

MassCOSH (Mass. Coalition for Occupational Safety and Health) |

| 42 |

Steve Greenhouse |

Labor Journalist

NYT |

| 43 |

Pascalle Grotenhuis |

Head of Division, Private Sector, CSR, and Infrastructure

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Netherlands |

| 44 |

Ulrik Haagerup |

General Director

DR TV |

| 45 |

Diane Hampton |

Global Compliance Manager

New Era Cap |

| 46 |

Auret van Heerden |

President

Fair labor Association |

| 47 |

Thuy Chung Hoang |

Journalist

VietNamNet |

| 48 |

Trong Ton Hoang |

Technical Manager , Boston Global Forum |

| 49 |

Viet Hang Hoang |

Office Manager, Boston Global Forum |

| 50 |

Sara Hossain |

Executive Director

Bangladesh Legal Aid & Services Trust |

| 51 |

Christiane Hullmann |

Permanent Mission of Germany to the United Nations |

| 52 |

Rubana Huq |

Managing Director, Mohammadi Group |

| 53 |

Atiqul Islam |

BGMEA President |

| 54 |

Shafiqul Islam |

Conselor, Commerce

Embassy of Bangladesh to the US |

| 55 |

Kent Jones |

Professor

Babson College |

| 56 |

Jason Judd |

Deputy

ILO/Better Factories Cambodia |

| 57 |

Lewis Kaden |

Chairman, Markle Foundation Board of Directors

Former Vice Chairman, Citigroup

Member, Markle Initiative for America’s Economic Future in a Networked World (Ex-officio) |

| 58 |

Tom Kochan |

Professor

MIT |

| 59 |

Christian Kopp |

Permanent Mission of Germany to the United Nations |

| 60 |

Denise Kotulla |

Permanent Mission of Germany to the United Nations |

| 61 |

Jeff Krilla |

President

Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety |

| 62 |

Lam Dac Le |

Vice President , Indochina Capital |

| 63 |

Deborah Leipziger |

Professor

Simmons College |

| 64 |

Richard Locke |

Director/Professor

Watson Institute for International Studies, Brown University |

| 65 |

Jonathan London |

Assistant Professor, City University of Hong Kong |

| 66 |

Amy Luinstra |

Head, Policy and research

Better work program

International Finance Corporation (IFC) |

| 67 |

Reaz Bin Madmood |

Vice President, Finance BGMEA

Managing Director, La-Belle Group |

| 68 |

Huu Tin Mai |

CEO,

U&I Group |

| 69 |

Bushra Malik |

Member Independent Oversight Advisory Board at International Labour Organization (ILO) |

| 70 |

Martin McAdam |

CEO

Aquamarine Power Limited, Irish |

| 71 |

Van McCommick |

Director

International Economic Alliance (IEA) |

| 72 |

Eileen McNeely |

Instructor

Department of Environmental Health

HSPH |

| 73 |

Richard Miller |

US House Committee on Education and Workforce |

| 74 |

Rajeshwar Mishra |

Chairman

Mishra Ispat Pvt. Limited, India |

| 75 |

Christain von Mitzlaff |

Managing Director

LIFT Standard e.K. & Bangladesh Representative, Business Social Compliance Initiative. |

| 76 |

Corrina Morrisey |

Section for Human Rights Policy, Human Security Division, Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, Switzerland |

| 77 |

Andor Nagy |

Hungarian Ambassador to Israel |

| 78 |

Sarah Neely |

Program Assistant at USAID |

| 79 |

Khanh Ngo |

Assistant to Editor-in-Chief, Boston Global Forum |

| 80 |

Tram Ngo |

Designer, Boston Global Forum |

| 81 |

Anh Tuan Nguyen |

Editor-in-Chief, Boston Global Forum |

| 82 |

Duy Hung Nguyen |

Chairman and CEO

SSI |

| 83 |

Giang Nguyen |

Head of East Asia

BBC |

| 84 |

Tuong Van Nguyen |

Performance and Risk Analyst, BNP Paribas Investment Partners |

| 85 |

Van Phu Nguyen |

Managing Editor

Saigon Times |

| 86 |

Scott Nova |

Member of Governing Board

Workers Rights Consortium |

| 87 |

Alexey Novoselov |

President

SCM Holding Company, Russia |

| 88 |

Dara O’Rourke |

Professor/Founder

UC Berkeley/Good Guide |

| 89 |

Kim Parker |

Senior Director at Sunshine Sachs |

| 90 |

Christina Passariello |

Journalist

Wall Street Journal |

| 91 |

Alex Patterson |

Photographer |

| 92 |

Thomas Patterson |

Professor, Harvard Kennedy School |

| 93 |

Anh Tuan Pham |

Deputy Editor-in-Chief

VietNamNet |

| 94 |

Duc Trung Kien Pham |

CEO of Red Square |

| 95 |

Uyen Nguyen Pham |

Board Member of VinaTex |

| 96 |

Eli Pollak |

Chair at Chemical Physics Department, Weizmann Institute of Science |

| 97 |

Ahmed Shahryar Rahman |

Director, Maketing, Beximco Textiles |

| 98 |

Sandra Rahman |

Professor of Marketing & Chair of Business & Economics, Framingham State University |

| 99 |

Nur Mohammad Amin Rasel |

Senior Deputy Secretary, BGMEA |

| 100 |

Paul Rice |

CEO/President

Fair Trade USA |

| 101 |

Margaret Rodriguez |

Havard Business School |

| 102 |

Md. Ruhul Amin Sarker |

Additional Secretary

Ministry of Commerce |

| 103 |

Albert Schmitt |

CEO

Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen |

| 104 |

Hedrick Smith |

Journalist/Political Analyst

NYT |

| 105 |

Khurrum Siddique |

Head of Operations, Simco Bangladesh Ltd. |

| 106 |

Jugjiv Singh |

CEO

Pearl Academy, India |

| 107 |

Kirpal Singh |

Associate Professor of English Literature & Creative Thinking, School of Social Sciences, Singapore Management University |

| 108 |

Jyoti Sinha |

Research Associate

MIT Sloan School of Management |

| 109 |

James Stone |

Chairman

Plymouth Rock |

| 110 |

Jeffrey Stookey |

Independent Professional Training & Coaching |

| 111 |

Robert C. Terry |

Activist, Author |

| 112 |

Stefan Theil |

Shorenstein Fellow

Former Bureau Chief of Euro Newsweek |

| 113 |

Tobias Thomas |

Director

Ecowatch, Berlin |

| 114 |

Trong Thuc Tran |

Managing Editor

Saigon Entrepreneurs |

| 115 |

Salil Tripathi |

Policy Director

Institute for Human Rights and Business |

| 116 |

Susumu Uneno |

General Manager

Mitsui & Company, Japan |

| 117 |

Ravi S. Vasudevan |

CEO

Texmaco Group , Indonesia |

| 118 |

Minh Khuong Vu |

Prof. NUS , Singapore |

| 119 |

Wesley Wilson |

Senior Director for Corporate Responsibility

Walmart International |

| 120 |

Shunji Yanai |

President

International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea |

| 121 |

Amer Yaqub |

Senior Vice President

Foreign Policy |

| 122 |

Melike Yetken |

Senior Coordinator for Corporate Social Responsibility, Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs, & U.S. National Contact for the OECD Guidelines, U.S. Department of State |

| 123 |

Shigeaki Yoshikawa |

Senior Vice President

Mitsubishi |

| 124 |

Arnold Zack |

Mediator/Professor

Harvard Law School |

by Admin | Sep 10, 2013 | Highlights

Read a moving speech made by Amirul Haque Amin, President of the National Garment Workers’ Federation to Trade Unions Congress on September 8, 2013.

Amirul Haque Amin addresses the TUC in September 2013

It is my pleasure that I represent Bangladeshi garment workers. This is an opportunity to share the conditions, the situation, the fight, the challenge, and the struggle of Bangladeshi garment workers with you, the members of the TUC.

Friends and comrades, while we are at TUC Congress, in Bangladesh there are still more than 100 injured workers of Rana Plaza who have been in hospital for the last four and a half months.

While we are at Congress, more than 500 children between 3 months and 8 years are in an uncertain situation, having lost their parents, some of them lost their father, some of them lost father and mother, both.

Nearly 1,400 injured workers, though discharged from hospital, still need more and better treatment.

In the Rana Plaza collapse 1,133 workers were killed and those 1,133 workers’ families and 500 injured workers are still waiting for compensation.

Five months before, on 24th November, a fire also happened in Tazreen fashion factory, where 112 workers were killed and another 150 workers were seriously injured.

From the Rana Plaza collapse, and the Tazreen fashion fire, it is clear that the Bangladeshi garment workers’ sector is not a safe workplace. That is the reason we, the local trade unions, as well as global trade union federations, with the support of foreign labour rights groups, initiated the Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety Accord; a union Accord.

Up to now, 86 multinational companies have already signed this Accord but, unfortunately, eight more multinational companies based in the UK, including Matalan, River Island, and Republic, did not up to now sign this Accord.

On behalf of the Bangladeshi garment workers I am asking you, please, raise your voice and send a very clear message to the eight companies to stop killing workers, end the death traps, come forward and sign the Accord, and ensure a safe workplace for Bangladeshi garment workers.

Friends and comrades, in Bangladesh at present, there are 5,000 garment factories, 3.6 million workers are working, and 85% of them are women. The garment and textile sector covers 79% of total exports.

But still today the minimum wage for the Bangladeshi garment workers is only £24 in a month. Even the skilled sewing machine operators only get between £32 to £42 in a month. Bangladeshi garment workers need a living wage.

As a local trade union we are fighting with our government. We are fighting with our local business people and factory owners but again to ensure the living wage for the Bangladeshi garment workers we need to campaign at multinational companies.

The multinational companies will say that, ‘Yes, the living wage is very important and this is needed for the workers,’ but, on the other hand, these multinational companies always are pressuring the local business people and factory owners to decrease the price of the product, so this situation is totally contradictory. On the one hand, they will advise for the living wage but, on the other hand, they will pressurise to decrease the price so that the living wage cannot happen.

That is the reason we again ask you to please send a very clear message, pay the fair price for the garment products to ensure the living wage for the Bangladeshi garment workers.

Friends and comrades, we know very well we are in the worst situation but we also know that you, the workers, and people in the UK are also not in a good position. You are also facing a lot of problems, especially in the case of social security, pensions, and other benefits.

Now is the time to fight together. This is the high time to work together. It’s high time to raise our voice in unity to challenge the multinationals together. Let’s fight united for better conditions, for a better life and for a better society.

Workers of the world unite! Thank you, everybody.

Take action

Show solidarity with Bangladesh’s garment workers by writing to the clothing brands who still need to sign the Accord. Send an email now via GoingToWork.org.uk

by Admin | Sep 10, 2013 | Highlights

‘Going to Work’ from Britain’ TUC

Britain’s Trade Unions Congress (TUC) is using its ‘Going to Work‘ campaign to mobilize the public to send emails and messages to companies that have refused to sign up to the Accord. Thus far, over 80 brands have signed on but major retailers have still managed to evade the system. The eight brands targeted by ‘Going to Work’ in their email campaign are: River Island, Matalan, Bench, Bank Fashion, Peacocks,Jane Norman, Republic and Mexx.

This campaign was launched after Amirul Haque-Amin, the President of the National Garment Workers Federation (NGWF) in Bangladesh made a moving speech to Congress describing the dreadful conditions garment workers are often forced to endure and the life-saving role trade unions play in providing them with basic safety and dignity at work.

Click here to read more about the campaign and to participate by sending a message to these brands.

Robert Kuttner is Meyer and Ida Kirstein Professor at Brandeis University’s

Robert Kuttner is Meyer and Ida Kirstein Professor at Brandeis University’s