On April 24, 2013 the Rana Plaza factory building collapsed in the Savar industrial district outside of Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. Over 1,100 people were killed in the worst industrial accident since over 2,000 people were killed (and 150,000 injured) in the Union Carbide plant gas leak in Bhopal, India. Most of the victims worked for the five garment factories housed in Rana Plaza, whose primary clients were European, US and Canadian firms. Export contracts to such firms had helped Bangladesh become the world’s second largest clothing exporter. Rana Plaza was not the first tragedy to occur in Bangladesh’s garment industry, and without intervention, more might follow. Following the Rana Plaza disaster, international brand owners, domestic and foreign governments, labor unions and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), began to discuss responsibilities for improving conditions for Bangladeshi garment workers.

The Bangladesh Garment Industry

Following independence from Pakistan in 1971, the Bangladesh government began privatizing industries to spur economic growth. The garment industry became a major force in Bangladesh after the Multi-Fiber Arrangement (MFA) was enacted in 1974. The MFA regulated the sale of garments and textiles from developing countries to first world countries. The MFA, which was in effect until 2004, imposed quotas on garment exports from Korea, China, Hong Kong and India. No quotas were imposed on Bangladesh’s garment exports and its industry grew from $12,000 worth of exports in 1978 to over $21 billion in 2012. Even after the MFA expired, Bangladesh maintained export volume, thanks to its low labor costs. In 2012, Bangladesh was the second largest garment exporter in the world, after China.

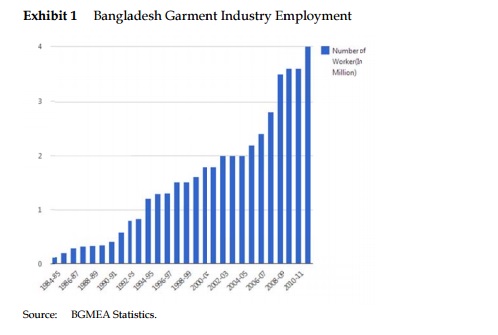

The garment industry was a major force in the Bangladesh economy. The industry employed 3.6 million people (and an additional million, through indirect employment) or roughly 2% of the population.6 The garment industry accounted for 13% of GDP. It was the single largest source of exports, 78% in 2011. (See Exhibit 1 for growth in garment industry employment over time). Workers in garment factories were paid approximately 13% more than workers in other industries. The vast majority of garment workers were women. In 2011, around 12% of Bangladeshi women between 15 and 30 years of age were employed in the garment industry.

Global Customers

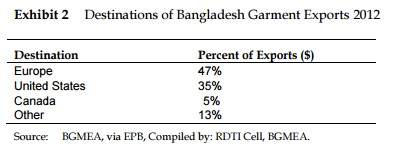

The majority of garments produced in Bangladesh were exported. In 2013, 2,000 out of 5,000 garment factories had export contracts, with many of the remaining 3,000 factories working as sub- contractors that provided additional capacity for the factories with international orders.11 Some multinational brands imposed strict limitations on the use of sub-contractors in their contracts ith primary suppliers, (in certain cases, processes existed for MNCs to grant permission for use of sub- contractors). It was also common for brands to employ agents to locate production capacity on their behalf. Nearly 90% of garments produced in Bangladesh were exported to the United States, Europe and Canada (see Exhibit 2 for proportionate export volume). In 2012, the US alone received $4.9 billion worth of garment exports from Bangladesh.

Many US and European fashion brands sourced items from Bangladesh. Brands with operations in Bangladesh included well-known global fast fashion labels H&M, Inditex (Zara), and Loblaw’s (Joe Fresh); as well as other low-to-mid priced labels like Wal-Mart, Gap, and PVH (Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger, Timberland). Many brands required garment production to align with the seasonal release of new clothing collections (in spring, summer, fall and winter). These production schedules caused large spikes in demand for capacity, with little room for errors, around the seasonal release dates, and lower demand at other times.

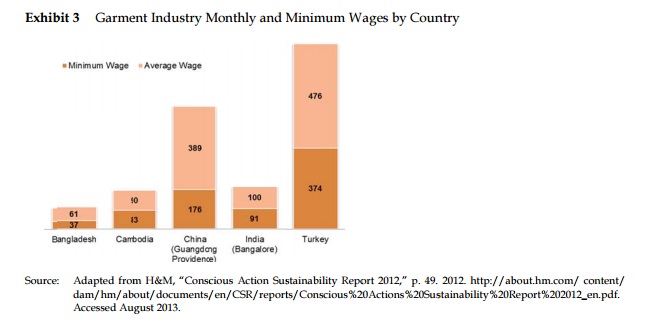

Low cost production and large capacity were key incentives for multinational corporations (MNCs) to produce garments in Bangladesh. The minimum wage in 2012 was $37 per month, and had only increased by $29 over the past 30 years. In comparison, China, the largest clothing exporter, had a minimum wage four times that of Bangladesh, and saw its labor costs increase by 30% in 2011 alone. As shown in Exhibit 3, Bangladesh’s minimum and average wages were far lower than those of other developing countries which produced garments for export. Combined labor cost differentials were expected to help Bangladesh’s garment industry to reach $30 billion by 2015.

Factory Conditions

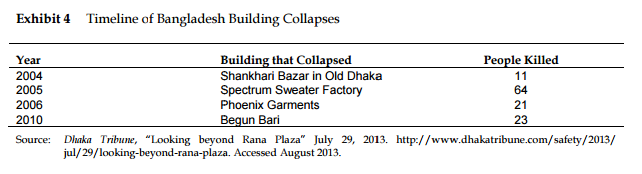

More than 1,000 garment workers were thought to have died and 3,000 to have been injured working in Bangladesh’s garment industry since 1990. (See Exhibit 4 for a list of industrial buildings which had collapsed in Bangladesh). The quick growth of the garment industry had resulted in fast construction of factories, often at the expense of adhering to building codes. The government feared foreign investment and export contracts would flow to other low cost garment producing countries if MNCs perceived Bangladesh’s factory safety record and labor disputes as risks to their brands. In 2012, the US Ambassador to Bangladesh shared with the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) details of a call he received from the U.S. CEO of one of Bangladesh’s largest garment export customers. The CEO stated his concern that “the tarnishing of the Bangladesh brand may be putting our company’s reputation at risk.”

The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) claimed to regularly monitor member factories for safety compliance. However, it was unclear the extent to which compliance was enforced. Following the Tazreen garment factory fire caused by unsafe storage of flammable materials in November of 2012, which killed over 100 workers, BGMEA inspectors were sent to member factories to check labor and safety compliance. Four of the buildings inspected, belonging to BGMEA President Atiqul Islam, were found to have numerous violations.

Numerous NGOs sought to improve labor and safety conditions for Bangladesh’s garment workers. Care Bangladesh partnered with MNCs to create programs to help female garment workers develop leadership skills. The Global Women’s Economic Empowerment Initiative, a partnership between Care Bangladesh and Wal-mart, helped nearly 24,000 female garment workers learn their legal rights and develop communication skills. Gap worked with Care Bangladesh to form the Personal Advancement and Career Enhancement Initiative for around 500 female garment workers employed in Gap’s supplier factories. Other NGOs, like the Awaj Foundation, empowered garment workers to understand and act upon their legal rights. The Awaj Foundation’s network included 255,719 garment workers and offered programs for workers on Bangladesh labor laws, fire safety, and health care services, among others. The Worker Rights Consortium inspected Bangladesh garment factories for labor violations but, over three years, it had only checked the factories associated with three factory owners. In 2007, the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity, (an affiliate of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations,) petitioned the U.S. government to suspend trade privileges for Bangladesh, in light of worker rights violations in the garment industry.

The Bangladesh government tried to suppress activities by labor unions and other groups who attempted to highlight poor safety conditions in the country’s garment factories. Bangladesh police and security forces were suspected in the 2010 murder of labor activist Aminul Islam, the president of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation’s in Savar and organizer of the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity labor rights group. He was detained and beaten by Bangladesh security forces and his body showed signs of torture after being recovered in 2012.

Rana Plaza

On April 23, the day before the building collapse, workers observed cracks in the walls of the Rana Plaza building. The building housed five garment factories; as well as a bank and shopping mall. That morning, an engineer who had previously consulted for Sohel Rana, the building owner, deemed the building unsafe and recommended that the workers be evacuated. Later that day, a local government official met with Sohel Rana. After the meeting, the official declared the building was safe, pending another inspection. The workers of the Brac Bank branch heeded the advice of the engineer and vacated the building. Garment workers were informed that they were expected to return to work in the building the next morning, to fulfill overdue orders, or risk losing their jobs.

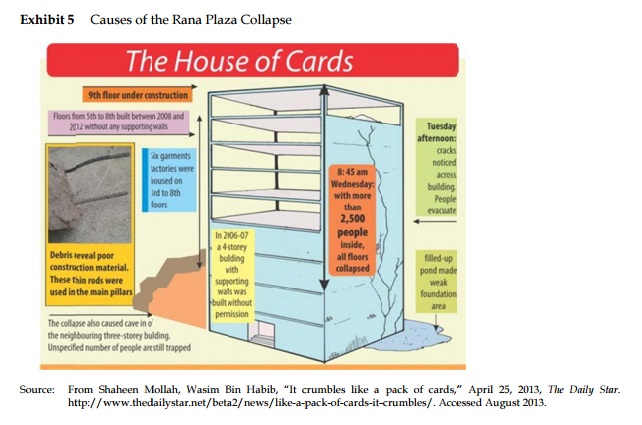

On April 24, 2013, the nine story Rana Plaza building collapsed, killing 1,100 workers and injuring 2,500 more. Sohel Rana was in his office in Rana Plaza when the disaster occurred; he fled but was arrested later at the Indian border. The disaster was caused by numerous structural problems (see Exhibit 5 for an illustration of the building):

- Four additional floors were constructed illegally upon the existing four stories, with a ninth floor under construction.

- The building lacked the supporting walls needed to hold heavy industrial machines and generators used by the factories.

- The lot where Rana Plaza stood was formerly a pond, which was filled only with sand.

- Inferior building materials were used to construct Rana Plaza.

To read the full Article please download Rana Plaza (A)