by Admin | Oct 14, 2013 | Highlights

Boston Global Forum (BGF) had another opportunity to speak with Arnold Zack, an Arbitrator and Mediator of over 5,000 Labor Management Disputes since 1957; former President of the Asian Development Bank Administrative Tribunal; designer of employment dispute resolution systems;; occasional consultant for the governments of the United States (Department of State, Peace Corps, Department of Labor, Department of Commerce), Australia, Cambodia, Greece, Israel, Italy, Philippines, and South Africa, as well as the International Labor Organization, International Monetary Fund, Inter-American Development Bank, and UN Development Program. He has also been a Member of Four Presidential Emergency Boards (chair of two). (Harvard Law School), and currently teaches at the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School.

BGF: Following up on our previous conversation, I had an opportunity to sit down with Professor Kent Jones of Babson College, who described the situation in which Cambodia came to be an ideal location for the International Labor Organization, and their offspring, The Better Factories Cambodia, to come in and establish reasonably acceptable working standards. However, Professor Jones also warned that further replication of the model is not possible elsewhere. What is your opinion on this matter and what else do you think a group like Boston Global Forum can do to address this issue?

Arnold Zack: The Cambodian situation arose during a unique period of history and can probably not be replicated at the moment. However, there was a piece in the Wall Street Journal on Sept 23rd, 2013 reporting that Better Factories Cambodia is about to begin publicizing compliance of firms with 21 standards, including worker rights, fire safety and treatment of unions. Several international brands and firms (including Wal-Mart) have endorsed the program while the Cambodian government and the Garment Manufacturers Association have opposed it. Such a program would not be possible without independence from Cambodian control, and freedom from the corruption that plagues national government intervention in most efforts and improving worker conditions in Southeast Asia

As to what the Forum could do, I would love to see a replication in some other countries in South East Asia, ie. Bangladesh, Myanmar or Vietnam. Such replication would have to come from more powerful organizations, although the focus on Bangladesh at the present might make that a possibility. I am not sure if the ILO is looking to be involved, even though they have set up similar programs in Africa.

Right now, I think the real need is getting existing Codes of Conduct implemented in these countries, and not focusing on establishing new ones. The Codes themselves are meaningless and multitudinous. Local factories ignore them. Ideally, local governments would help enforce them as in the case of Brazil, where graft is not such a problem. That is why international initiatives such as by the ILO are keys to advancement. I do not think the WTO is a player or wants to be. They are serious about enforcing intellectual property covenants and codes, but have clearly restrained themselves from involving in any social clauses or workplace codes.

Finally, I don’t think there is any route through the World Bank or the IMF. Having been involved with both organizations over the years (I led a survey team on reforming the Funds internal dispute resolution system), I can attest to their disinterest in social responsibility issues. Individual staff members might be interested but their focus is necessarily on dealing with financial and fiscal problems of governments and in gigantic infrastructure projects with no jurisdiction over workplace conditions.

Related article:

by Admin | Oct 7, 2013 | Highlights

Even though safety standards have improved somewhat, Bangladeshi factory workers are still being abused due to wage and overtime violations carried out by their supervisors. Unfortunately, this situation is caused by the flawed monitoring activities by big brand names, including the Gap Inc. VF Corp., which owns The North Face, Wrangler and Nautica, and PVH Corp., which owns Tommy Hilfiger. Clearly, these multinationals need to step up their monitoring efforts as they recently all made pledges to crack down on poor working conditions in their subcontractors’ factories.

Shelly Banjo of the Wall Street Journal has the story.

DHAKA, Bangladesh—Next Collections Ltd., one of more than two dozen factories owned by one of Bangladesh’s largest garment producers, tells buyers its workday runs from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m.

On a recent Saturday night, however, bright fluorescent lights flickered well past 10 p.m. as workers inside furiously stitched children’s skinny jeans bound for Gap Inc.’s Old Navy stores.

The company regularly keeps many of its 4,500 workers late—sometimes until 5 a.m.—to meet production targets set by retailers like Gap, VF Corp. and Tommy Hilfiger parent PVH Corp. The workers themselves sometimes welcome the extra pay, but the practice apparently conflicts with the retailers’ stated policies and a Bangladeshi law that prohibits more than 10 hours of work a day, including two hours of overtime.

Photo: Shelly Banjo/The Wall Street Journal

Photo: Shelly Banjo/The Wall Street JournalMohammad Mazharul Islam, a former worker at the Next Collections factory, where he alleges he was beaten.

The late hours at the Next Collections factory show the challenge retailers face in trying to police supply chains that can run to hundreds of factories in several countries. It also makes clear that recent pledges by retailers to crack down on poor working conditions in the wake of multiple deadly disasters in Bangladesh’s textile industry won’t amount to much without careful follow-up to monitor compliance.

Ha-Meem Group, which owns Next Collections, didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment. In an interview with The Wall Street Journal earlier this year, owner A.K. Azad said the company is eager to keep its workers happy.

Next Collections’ gray concrete compound, located along a dirt road in the congested outskirts of the Bangladeshi capital, keeps two sets of records and pay slips, according to interviews with nearly a dozen current and former workers and managers, and supported by pay documents reviewed by the Journal and a current manager at the factory group.

“It is easy, because auditors and buyers never come around late at night to check these things,” the current factory manager said in an interview. “Sometimes, it is the only way to meet the orders on time.”

From June through September, one set of computer-generated pay slips provided to buyers and reviewed by the Journal depicts a 48-hour workweek with no more than 12 hours of overtime. Another set of handwritten documents, confirmed by the current manager, outlines which workers received dinner stipends worth about 40 cents for working past 1 a.m. That set of documents appears to show that many employees were in fact routinely working more than 100 hours a week.

Photo: Shelly Banjo/The Wall Street Journal

Photo: Shelly Banjo/The Wall Street Journal

Next Collections keeps two sets of books on workers. The handwritten one logs late hours for worker 43012, not shown on the pay stub.

Many of the factory records were provided to the Journal by the Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights, a workers’ rights nonprofit based in Pittsburgh. Order and production records as well as clothing labels reviewed by the Journal show that the factory recently fulfilled orders for Gap, VF and PVH. Some of the workers interviewed for this article were referred to the Journal by the institute.

VF, whose brands include The North Face, Wrangler and Nautica, has decided to stop placing work with Next Collections after finding repeated violations of its standards on wages and hours worked, according to spokeswoman Carole Crosslin. She said VF will still place orders with other Ha-Meem Group factories.

A VF compliance officer found some of the violations during an audit in January. A review in March showed the factory had made progress, but the company pulled out after another check on Sept. 23 showed the problems had returned, according to Ms. Crosslin.

“Based on our audits of Next Collections and the unwillingness of the factory’s management to fully partner with us to meet and sustain compliance with our standards, we are planning to exit the facility,” Ms. Crosslin said.

Photo: Saima Kamal for The Wall Street Journal

Photo: Saima Kamal for The Wall Street Journal

At the Next Collections factory, lit up in the far background, garment workers are sometimes kept until 5 a.m.

Gap said it launched an investigation into possible violations of its standards in response to inquiries by the Journal last week. It has interviewed 50 current workers and management but has yet to reach a conclusion.

“Our contracts require that factory management pay overtime and abide by all local labor laws and industry standards,” spokeswoman Debbie Mesloh said. “Should these allegations prove to be true, Gap Inc. will take action, up to and including terminating its business relationship.”

A spokesman for PVH said the company’s records show it hasn’t produced at the facility since early 2011 but that it would continue to look into possible unauthorized production, such as work that is subcontracted to the factory without PVH’s knowledge.

PVH, based in New York, has signed on to an accord led primarily by European companies that sets legally binding rules for safety improvements at Bangladeshi factories funded by retailers and apparel companies. Gap and VF have joined a separate pact led by American companies that isn’t binding and will help finance improvements that will be paid for by the factory owners. Both accords set up inspection regimes that are aimed at weeding out unsafe factories.

Labor groups and safety experts say fair treatment of workers and the sorts of practices that make factories less disaster prone go hand in hand. In many deadly incidents, workers have noticed problems but were ignored by managers focused on meeting orders.

That includes the Rana Plaza garment factory, where workers were alarmed by new cracks in the building but were forced to go back to work. The collapse of the building in April killed more than 1,100 people. The incident and a series of deadly fires that have killed hundreds more have focused international attention on safety conditions in Bangladesh.

Conditions at factories like Next Collections show that even if factories add fireproof doors and shore up cracks, the economics of a garment business that awards short-term contracts to the lowest bidders means factories still face pressure to violate wage and hour policies to compete, according to Charles Kernaghan, director of Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights.

Abundant workers who are among the lowest paid in the world have helped make Bangladesh one of the largest exporters of clothing for Western consumers hooked on cheap goods. The country’s minimum monthly wage stands at 3,000 taka, or about $40. Workers have held protests across the country in an effort to raise it to about $100.

Ha-Meem Group is a big player in the industry. The group of factories is run by Mr. Azad, the former president of the Federation of Bangladesh Chambers of Commerce and Industry and the owner of a prominent Bangladeshi television station and newspaper.

Next Collections began production in 2011 to absorb orders after a fire damaged another Ha-Meem Group factory nearby. The 2010 fire at That’s It Sportswear—which was producing clothes for the Gap, PVH and J.C. Penney Co. —killed at least 27 workers and injured 100 others.

Following a public outcry, Gap, PVH and Penney sent a letter asking Mr. Azad and Ha-Meem Group to improve safety at their factories. Gap stayed with Ha-Meem Group as the textile conglomerate made improvements to its buildings and strengthened its fire safety protocols.

In the interview earlier this year with the Journal, Mr. Azad said his company was working hard to upgrade factories, especially given safety concerns following the Rana Plaza disaster. He said the company had set up an internal committee to study improvements and planned to add sprinkler systems, among other steps.

“Customers are very concerned,” he said. If there is another major factory disaster in the country, he said, “Bangladesh will be history for garments.”

Workers and managers at the Next Collections facility say they feel the building is safe. Workers say they are comfortable navigating escape routes and handling equipment in case of a fire. Doors are typically unlocked, and regular fire safety drills are conducted, they said.

Still, current and former workers at Next Collections allege that hours are long and that managers shortchange their wages, force resignations from pregnant staff, deny workers maternity and holiday benefits, and physically abuse and verbally harass employees who are found to be trying to form a labor union.

In one case, former worker Mohammad Mazharul Islam said the factory’s managing director beat him with a stick so forcefully that he spent four nights in a nearby hospital, according to his accounts and hospital records reviewed by the Journal. The 25-year-old has since started another job at a garment factory nearby.

Commitments to improve such conditions can be hard to verify.

“None of the buyers can understand what goes on when they are not there,” said Azim Sheikh, a 26-year-old ironer at the factory who says he makes about $56 a month.

by Admin | Sep 27, 2013 | Highlights

[For Part 1 of our discussion, please click here]

Dr. Jones specializes in trade policy and institutional issues, particularly those focusing on the World Trade Organization. He has served as a consultant to the National Science Foundation and the International Labor Office and as a research associate at the U.S. International Trade Commission, and was senior economist for trade policy at the U.S. Department of State. Dr. Jones is the author of numerous articles and four books, including Politics vs. Economics in World Steel Trade, Export Restraint and the New Protectionism, Who’s Afraid of the WTO? and most recently, The Doha Blues: Institutional Crisis and Reform in the WTO.

In light of some recent developments Boston Global Forum (BGF) has made, we had an opportunity to sit down with Professor Kent Jones of Babson College again to explore other possible solutions for our topic. Readers of our previous posts may have noticed that BGF was able to identify Better Factories Cambodia as a possible model for other countries to replicate. However, according to Professor Jones, there is a reason why this strategy may not be possible.

BGF: Many experts attributed the success of Better Factories and the International Labor Organization’s involvement in Cambodia to a trade agreement between the U.S and Cambodia in 1999, which basically required improved labor conditions for factory workers in exchange for a higher percentage of quota for garment exports into the U.S. If this is the case, why do you think that the U.S government, or any other Western powers, did not re-implement a similar agreement in order to incentivize local authorities to come up with better working conditions for garment workers in their countries?

Professor Kent Jones: There was indeed a formal special textiles/clothing trade agreement between Cambodia and the US in 1999, which led to improvements in working conditions there. Unfortunately, the circumstances that allowed this agreement have changed, and it is no longer possible to replicate it for other countries.

At the time, Cambodia, like all other developing countries, was subject to the Multifiber Agreement (MFA), a global system of trade quotas on nearly all categories of clothing sold in the US, Europe and other industrialized countries. Each exporting country typically had certain quota shares in the US market, which were strictly controlled.

The US-Cambodia agreement was designed to provide an incentive for Cambodia to improve worker rights and working conditions in exchange for significant increases in its quota access to the US market. As part of the arrangement US AFL-CIO representatives went to Cambodia to organize workers there and monitor progress. There were controversies during those years as to how much progress was being made, but in the end Cambodia did receive increased market access as a result of the reforms that took place.

There were two important elements of the deal that were crucial in making it work. One was that the MFA ruled the world textile/clothing market. This global system of quotas allowed countries like the US to offer special deals to certain countries based on criteria such as progress on worker rights (other deals were based on political criteria). The second element was that Cambodia was not in the WTO; it joined eventually in 2004.

These circumstances were important because the MFA was being phased out at the time for members of the WTO, based on the new agreements of the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations, completed in 1994. As long as the MFA was in force, Cambodia could benefit from its special agreement on market access with the US, since all other countries were restricted by MFA quotas. As the MFA was phased out over the period 1995-2005, all WTO countries were gradually allowed more and more unfettered access to the US and European markets, which was eroding the benefits of any extra quota access granted to Cambodia.

Still, the US-Cambodia deal allowed the US to continue the incentive program until Cambodia joined the WTO (after a long accession process) in 2004. At that point, Cambodia was entitled to the full benefits of the MFA phase-out that was completed in 2005. The US no longer had any leverage to control Cambodian market access to the US, based on the MFN treatment Cambodia received upon joining the WTO, and the MFA phase-out that now applied to Cambodia as well.

We now have a quota-free global trading environment in textiles and clothing. Tariffs are still imposed on these products, but they are regulated by the WTO tariff binding rule, which prohibits countries from raising tariffs unilaterally. In addition, the MFN rule prohibits WTO members from raising tariffs against any other individual WTO member on a discriminatory basis. Thus a deal like the earlier US-Cambodia agreement would no longer be possible for any WTO members, including Bangladesh.

The legacy of the agreement was that it gave the ILO, workers’ rights and labor unions a foothold in Cambodia, and these groups continue to have some impact there. Improvements in working conditions and worker rights in Bangladesh and other countries will have to come from other strategies besides intergovernmental trade deals.

This is why, as I suggested in our discussion a few weeks ago, that company codes of conduct, backed up with consumer group or NGO pressure, would be the most promising path.

Otherwise, a formal plan for improving a country’s work environment would require the government itself to agree to ILO and/or outside group monitoring of labor conditions. The US and other countries may need to find other means of leverage in order to persuade reluctant governments to implement reforms.

BGF: Thank you for your insights, Professor.

by Admin | Sep 26, 2013 | Highlights

In its September monthly meeting, the Boston Global Forum looks at successful labor-rights implementation models and ways to implement these models in Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Cambodia .

Photo: Arnold Zack (left) with Governor Michael Dukakis at the BGF meeting

The Boston Global Forum has been working feverishly to find pragmatic solutions that can ameliorate health and safety conditions of garment factory workers in Bangladesh. In order to prevent another disaster like the Rana Plaza collapse or Tazreen factory fire, we have garnered support from impassioned government and academic leaders who are committed to devoting their time, knowledge and insight to the cause. In BGF’s September monthly meeting held on September 18, 2013, Governor Michael Dukakis, Arbitrator and Harvard Law School Researcher Arnold Zack, Harvard Business School Professor John Quelch and Co-Founder and Editor-in-Chief Mr Nguyen Anh Tuan met in Cambridge, Massachusetts to share proceedings from the month previous and divulge ideas to accelerate the movement.

Chaired by Governor Dukakis, BGF’s monthly meeting opened with a discussion and analysis of the recent two-day conference held at New York University’s Stern Center on Business and Human Rights on the future of the garment industry in Bangladesh with reference to human rights issues. Major US and European retailers, governmental organizations, Bangladeshi officials and other key players were invited to participate in the conference. In realization of the need to both organize another round-table discussion and to ensure greater participation, Mr Tuan proposed an online conference, organized by BGF, in the coming months.

In this month’s meeting, the crux of the conversation was on the search for model third-world countries where international labor law standards have been successfully and sustainably demonstrated. Rising to the top was the International Labor Organization’s Better Factories Cambodia program. Formerly known as the ‘ILO Garment Sector Project’, Better Factories Cambodia rose out of a trade agreement between the United States and Cambodia in 2001 through which the US assured Cambodia access to its markets in exchange for improved working conditions in the garment industry. The ILO works closely with the Cambodian government, the Garment Manufacturer’s Association in Cambodia and international retailers to ensure safe and conducive working conditions in Cambodia.

Better Factories Cambodia employs multiple assiduous approaches to implement the highest possible safety standards in garment factories. Mr Zack said that the ILO uses a monitoring and evaluation procedure based on 500 different elements addressing fundamental issues like child labor and freedom of unions, and selective issues like over-time wages, maternity leave and protective equipment. The results then feed into extensive reports that detail levels of compliance of garment factories to these factors.

The success of Better Factories Cambodia also lies in its unique labor dispute resolution mechanism- the Arbitration Council. This national tripartite institution is made up of representatives from labor unions, the ministry and factory owners. All labor cases and conflicts are brought before the council that has developed a reputation for fairness and independence. The success of this form of mediation has made the council a model for judicial reform in Cambodia. Such is the triumph of Better Factories Cambodia that “factories from China are now relocating to Cambodia”, said Zack. He adds that retailers are proud of their association with ethical working conditions, in Cambodia, and are not discouraged by being held accountable to international standards.

Despite its success, the Cambodian model has been replicated in only a handful of countries, for instance in Lesotho. Thus far, it hasn’t been applied to Bangladesh. Troubled by the program’s limited expansion, Governor Dukakis raised provocative questions at the BGF meeting: “Why haven’t the U.S. and other interested countries been pushing it? Why aren’t we and others actively advocating for it?” Upon consequent research by the BGF team, it was discovered that the answer might lie in the understanding the transition from a global system of trade quotas called the ‘Multifiber Agreement’ to the WTO’s quota-free trading environment.

Governor Dukakis and John Quelch discuss future steps for the BGF

After deliberating over ILO’s Cambodian model, members of the Boston Global Forum steered the discussion towards other possible strategies to address the ‘Issue of the Year’. One key approach proposed was recognizing the importance of consumer education and pressure in maintaining international standards. Another approach suggested was for BGF to focus on work place safety under the larger aegis of worker rights. Professor Quelch introduced a broad-picture paradigm to the discussion by asking whether BGF should focus on Bangladesh alone or persevere for an all-ASEAN absorption of ILO standards? In support for the Cambodian model, he also suggested that BGF should research the reasons behind the success of the Cambodian model and publish its findings online as a statement of advocacy.

In closing, Professor Quelch reminded the BGF about the need to collaborate with experts in the field by inviting their participation through written commentary and statements on the website. He also proposed actively reaching out to Michael Posner, Labor Rights Advocate and head of the Stern Center for Business and Human Rights to demonstrate our willingness to aid his efforts on the issue.

The Boston Global Forum will work on these propositions in the coming month and will convene for another round of discussions in October 2013. If you wish to join our conversation or participate in our meetings, please send in your request to our Editor-in-Chief, Mr Nguyen Anh Tuan at [email protected]

by Admin | Sep 28, 2013 | Highlights

Shruthi Rao has over a decade of experience in sustainability project management, from inception to implementation. She has worked on environmentally sustainable projects across various industries, including education, newspaper publishing, and IT, encompassing areas such as carbon and water footprint analysis, data center energy efficiency, life cycle assessment (LCA) and e-waste management, and building business case for renewable energy. Working at A Clean Future (ACF) as a managing consultant, Rao is currently expanding her study of sustainability to the garment industry keeping in mind all three levels- health, social and environmental.

BGF- Is it possible to make fashion, which is such a niche and extravagant industry, sustainable?

Rao- Absolutely! It can be made sustainable and we want to start with apparel in the light of the recent events in the garment industry. Not only are there labor issues and work place safety issues but fashion is also one of the most environmentally polluting industries, especially with chemicals and water. ACF has a think tank component that is aimed at bringing people together to talk about what are the gaps that need to be identified for sustainable fashion. When we did some research, we looked for markers of sustainability of the fashion industry. Food industry has labels, construction has ‘green building’ options, but there is nothing for apparel, nothing that says how sustainably they were made. That is the talk of 2013. We at ACF want to look at sustainability from sourcing of raw material to manufacturing to production to use and disposal.

BGF-What is the final aim of ACF’s project?

Rao-As a think tank we try to identify gaps. The history of the fashion-industry shows that it is not a forward-thinking industry, not even their technology and business models. But what they respond to, very quickly, is consumer demand. The only way to bring about change in the industry is by leveraging consumer demand. We realized that there was no way to convey to consumers, while they shop, whether the garment was made sustainably or not. Currently, the only way is to research brand reputation and brand reputation can be easily skewed or mislead. We started looking for product-level information for consumers. Every garment bears information on how to iron or wash or where it was made, but nothing on how it was made. So we decided to conduct a market assessment to see if consumers would be interested in such information at a product level. We launched our internet survey about a month ago and 400 people have already filled it out. Our plan is to publish our findings about this consumer insight in a white paper and then raise awareness on how much consumers would like to know about these issues. We are trying to understand what are those cultural idiosyncrasies are that make consumers choose one garment/brand over another. We want to find out all aspects of sustainability and then find a way to describe it in a simply packaged manner- like a label on a garment. We also want to speak with fashion industry representatives and see what’s possible for them and if they would be ready for a label. We think companies like Patagonia and Eileen Fisher would be interested in communicating their responsible actions to people. We are also interested in finding out if retailers and departmental stores would be interested in reserving a section for sustainable clothes if brands and consumers express interest and willingness.

The Sustainable Apparel Coalition came up with the Higg Index – a standardized way of collecting information from all companies. From the industry-side there is effort going on. But there is not much happening at the other end. We hoped to bridge the gap and initiate effort from the consumer side too.

BGF-How will you source information on sustainability and how do you plan to present it?

Rao-We can’t go by what brands say so we are looking at combining information from each brand to get this information. For this, we’ll refer to the Higg Index. The Higg Index is a way of organizing all available brand information such that it is easily and readily available to the public. If I want to, I can go to a company’s annual report to find out how sustainable they are but for an end consumer, this is not always possible. We are looking into different methods- either take information from the public domain and display it, or communicate with fashion brands and use their information to convey it to consumers or work with Sustainable Apparel Coalition to deliver their research. We’re conducting an evaluation project to assess which method works best.

Our aim is to avoid confusing labels, like the ones that exist in the food industry. We want to standardize our information and present it in a way that resonates with the larger group not just the ones who are sustainably inclined. We want the information to be readily available so consumers don’t have to conduct independent research. Campaigns like GoodGuide are good for people who care enough to look. We want to find a way that makes product information available without the extra step of searching for it.

As our next step, we want to do industry surveys and get industry feedback on how to present this information about sustainability to consumers.

To read more about ‘A Clean Future’s’ sustainable fashion initiative and its consumer survey, please click here.

by Admin | Sep 27, 2013 | Highlights

Even though championed by many people as the representative model for the improvement of international labor standard, Better Factories Cambodia has recently come under pressure and criticism from both the Cambodian government and the factory association when the group decided to introduce an extensive initiative to improve garment workers’ conditions. This dilemma comes as the authority argues that tougher supervision will force businesses out of Cambodia and into less-regulated neighboring countries. This is clearly an existing paradox that any country must solve. If you were the Prime Minister or President of Cambodia? What should you do?

Boston Global Forum will work on these propositions in the coming month and will convene for another round of discussions in October 2013. If you wish to join our conversation or participate in our meetings, please send in your request to our Editor-in-Chief, Mr Nguyen Anh Tuan at [email protected]

The original story was reported by Kate O’Keeffe of the Wall Street Journal.

U.N.-Backed Group to Publicize Safety Failings Over Government Objection

A monitoring group backed by the United Nations said it would begin to publicize garment factories’ compliance with worker rights and safety standards in Cambodia, a controversial program that its organizers say will be the world’s most extensive initiative to improve working conditions at plants.

Photo: European Pressphoto Agency

Photo: European Pressphoto Agency

A group plans to publicize compliance with worker rights at garment factories. Above, a Cambodia facility.

The program, which Better Factories Cambodia began rolling out on Friday, comes as the global garment industry faces increasing pressure to improve conditions after the collapse of a garment factory in Bangladesh killed more than 1,100 people in April.

Accidents also have occurred in Cambodia recently, including two at factories in May, one of which left two people dead.

But Cambodia’s government and the country’s factory association have opposed the new program, saying it could wind up shaming only some factory owners and driving business to other countries where oversight is less rigorous.

The Better Factories program, set up by the U.N. and other groups a dozen years ago to improve conditions in Cambodia’s garment trade, is trying to reassert itself after coming under fire from some worker advocacy groups for not doing enough to improve factory conditions. Better Factories, among other things, inspects manufacturing facilities for problems such as child labor and unsafe conditions and offers training for factories to upgrade but has no enforcement power.

Jill Tucker, Better Factories Cambodia’s chief technical adviser, said she hoped that the new push to publicize compliance with worker rights and other standards not only will improve factory conditions in the Southeast Asian nation, but also will pressure people in the garment industry in other countries.

Getting support for the plan from all of Better Factories’ financial backers—which include the Cambodian government, the garment manufacturers’ association, unions, international buyers and foreign governments, such as the U.S.—has been a challenge, Ms. Tucker said.

Sat Samoth, undersecretary of state at Cambodia’s Labor Ministry, said the disclosure plan would violate a memorandum of understanding between the government and the U.N. International Labour Organization.

And the plan won’t help workers, Mr. Sat said. “If we disclose the names of the factories, and then the buyers stop purchasing the products, what will happen to the workers? They will lose their jobs,” he said. The government punishes factories that break the country’s labor laws.

Ken Loo, secretary-general of the Garment Manufacturers Association in Cambodia, called the Better Factories plan an example of “vigilante justice” and said that any change at factories has to be “demand-driven.”

“Consumers talk, talk, talk. But at the end of the day, they just buy the cheapest thing on the shelf,” he said.

Photo: Will Baxter/Bloomberg News

The Garment Manufacturers Association in Cambodia called the plan ‘vigilante justice.’ Above, workers leave a truck at the end of a workday in the country.

Starting this January, Ms. Tucker said, Better Factories plans to release information on a new website about the performance of all factories it has inspected at least twice regarding 21 issues, such as wages, worker rights, fire safety and treatment of unions.

Currently Better Factories Cambodia submits confidential reports to factories, whose business partners have the option to buy them. It also publishes public summaries that don’t name plants.

Under the new program, factories that have had three or more Better Factories inspections and still fall two standard deviations below the mean for compliance will be subject to an even higher level of disclosure. About 15 of the 450 factories the program monitors currently would fit that description. The public will see how they measure up against 53 legal requirements.

During the first year of the initiative, factories will get one opportunity to resolve any violations before they are disclosed. From then on, their performance will be published without negotiation.

Wal-Mart Stores Inc. the world’s largest retailer by sales, applauded Better Factories Cambodia’s plan. “We know that transparency is vital to make progress in improving factory conditions throughout the global supply chain, and can only be accomplished by working with stakeholders across the industry,” it said.

Sweden-based H&M Hennes & Mauritz AB also expressed support for the plan and said it wouldn’t lead the retailer to abandon any potentially problematic plants without good reason.

“H&M is aware of the challenges the factories in Cambodia face,” said spokeswoman Andrea Roos. The company doesn’t immediately stop working with factories if problems are detected, she said. As long as factories take negative findings seriously and commit to resolving issues, H&M prefers to maintain long-term relationships with them, Ms. Roos said.

Kong Athit, vice president of the Coalition of Cambodian Apparel Workers’ Democratic Union, said the Better Factories initiative would give the union more ammunition to pressure brands to force their factory partners to improve conditions.

Created a dozen years ago, the Better Factories program in Cambodia initially had a powerful weapon to encourage factories to improve: Under a 1999 trade deal, the U.S. offered to expand access to its market, which had quotas on garment imports, if Cambodian companies improved labor standards.

The 2005 expiration of the quota system left the Better Factories program without much leverage to pressure factories. It also enabled manufacturers to campaign successfully for Better Factories to stop naming them in their public reports, which, the companies said, could hurt their business, said Sandra Polaski, a deputy director general of the U.N. International Labour Organization.

Mr. Loo, of the manufacturers’ association, said the factories weren’t powerful enough to have forced the program into making the change.

Ms. Polaski and Ms. Tucker said the decision was a bad one that eroded the program’s progress in the country.

The ILO now is pushing for greater transparency in all of its monitoring programs globally. The organization’s Better Work Haiti program publicly discloses key portions of its factory audits, though the garment industry there is quite small.

In Bangladesh, following the Rana Plaza disaster, a consortium of more than 80 brands signed a fire and building-safety accord, which will publicly disclose factory performance.

David Welsh, Cambodia program director for the Solidarity Center, a nongovernmental organization affiliated with the U.S.-based AFL-CIO labor group, said that if any stakeholder in Cambodia doesn’t get on board with the new Better Factories proposal, “it’s a de facto admission that they either can’t or won’t monitor what’s going on in their factories and an admission that presumably, they suspect what’s going on doesn’t meet international labor standards.”

by Admin | Sep 25, 2013 | Papers & Reports, Highlights

Professor John Quelch, the co-founder and member of Board of Director of Boston Global Forum, is a distinguished Professor of Business Administration, who has has recently authored a Harvard Business School case study on the tragic Rana Plaza garment factory collapse that claimed 1127 lives on April 24, 2013. The case study offers an insightful snapshot of the reform analysis needed in the garment manufacturing industry. He currently leads the discussion on Boston Global Forum on this globally challenging complex issue.

His study recognizes that the Bangladeshi parliament, cornered by domestic and international pressure following this tragedy, ratified changes to their Labor Acts earlier this summer. The case study examines the systemic failure of government protection of human rights for garment factory employees, extols the need for adherence to the principles of socially responsible manufacturing and provides an overview of the cooperation pact signed by 80 global retailers and two labor unions to improve working conditions in Bangladesh.

The Bangladesh Garment Industry

The Bangladesh Garment Industry was a major force in its economy, employed about 3.6 million people or roughly 2% of the population. Its export value was worth $21 billion in 2012, and accounted for 13% of GDP in 2011. Nearly 90% of garments produced in Bangladesh were exported to the U.S, Europe and Canada. In 2012, the US alone received $4.9 billion worth of garment exports from Bangladesh. Low cost production and large capacity were key incentives for multinational corporations (MNCs) to produce garments in Bangladesh. Combined labor cost differentials were expected to help Bangladesh’s garment industry to reach $30 billion by 2015.

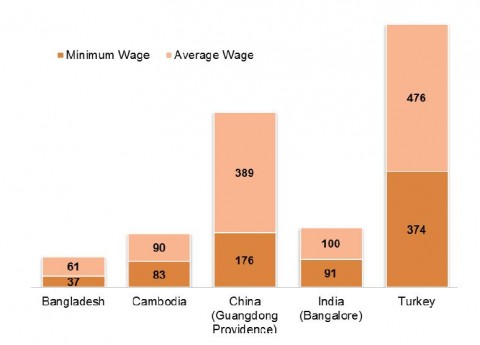

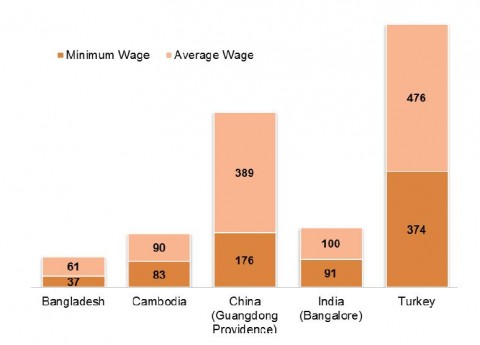

Garment Industry Monthly and Minimum Wages by Country

On April 24, 2013, the nine-storey Rana Plaza building collapsed, killing 1,100 workers and injuring 2,500 more. The disaster might be prevented due to the fact that there was a warning of the building unsafe and recommendation that the worker be evacuated by an engineer to the building owner. However, it was passed over in silence, and by the declaration of a local government official that the building was safe.

And MNCs’ response….

After the collapse, MNCs with operations in Bangladesh had several options on how to respond to the Rana Plaza tragedy.

MNCS were not directly responsible for the disaster, and many MNCS that had already been conducting factory inspections (like Wal Mart) would continue to do business as usual, and retain private records of infractions with no obligations to alert workers of safety hazards.

Some MNCS decided to shift all of its production away from Bangladesh to other , lower risk countries (like Disney corporation) in order to lessen the risk of negative press or irresponsible labor practices tainting the brand.

The other MNCs could decide to remain its manufacture in Bangladesh and partner with factories to improve safety conditions in the garment industry.

by Admin | Sep 16, 2013 | News

The Massachusetts Coalition for Occupational Health and Safety, or simply MassCOSH, is a Boston-based organization striving to improve work place safety, security and health throughout the state. The team collaborates with unions, legal and health professionals and community groups to voice and address issues faced by vulnerable communities in their work places. MassCOSH Executive Director, Marcy Goldstein-Gelb describes the organization’s focus areas for action and echoes the shared vision of worker welfare with Boston Global Forum.

In the summer 2006, tragedy stuck busy downtown Boston when a scaffold plunged from a building onto the congested road below. Falling with the three-ton structure were two workers who did not survive the impact. The heap of steel and material also crushed one of the many cars below, killing a young doctor who worked close by. The loss of life was widely covered by the media, with the Boston Globe noting that there was going to be a “hunt for answers” by state leaders to prevent such workplace deaths from ever happening again.

However, when Yogambigai Pasupathipillai was killed in August while working at aMalden bakery, there was no “hunt” by state leaders or reporters swarming to the scene. Unless you were a family member mourning such a devastating loss, you probably never even knew about the accident at all.

Yogambigai became yet another victim to an epidemic that silently claims the lives of hundreds of thousands of people every year – workplace fatalities. Here inMassachusetts, the Massachusetts Coalition for Occupational Safety and Health, or MassCOSH, a nonprofit worker safety organization, has found that, on average, a worker dies on the job each week due to dangerous conditions and hundreds more suffer from serious illnesses due to a work-related exposure that robs them of their health and vitality. When these events and exposures occur, families and co-workers mourn, but it rarely makes the papers. When the media does notice, it is often referred to as a freak accident, not a preventable incident worthy of a “hunt for answers”.

Here at MassCOSH, where workers and families contact us each day with horror stories of poor conditions, debilitating injuries and threats of retaliation for reporting an injury, we double down our efforts to ensure every worker has the right to a safe, secure job. At every level of our communities – from workers, to employers, to government enforcement agencies to elected officials, we all have an obligation to end tragic and nearly always preventable job injuries, illnesses and death.

At MassCOSH, we believe state policymakers can literally be lifesavers if they have a vehicle for gathering stories of workplace accidents and analyzing what can be done to prevent them from happening again. Here in Massachusetts, we are fortunate to have a nationally recognized state Occupational Health Surveillance Program within the Department of Public Health which is dedicated to doing just that. Unfortunately, they are grossly underfunded, depending primarily on federal grants, and the critical data they collect is not analyzed with the same public scrutiny the way our state budget line items and gambling forecasts are.

At MassCOSH we work hard to bring forward the stories of workers , issue reports combining state and federal data to educate elected officials, and alert the community to the needless workplace deaths that plague our state so that we can have a collaborative approach to creating policies that save lives. A recent success of this strategy was the 2010 passage of a state ban of a deadly floor finisher, the first in the nation. For over a year, MassCOSH convened a task force to investigate a highly combustible floor finisher that killed three workers in massive blazes and caused home fires across the state. The stories and data were irrefutable: the product was unnecessary and caused harm to workers and home-owners. Without a united front of workers, data, and allies, the fatal product might still be in use today. Instead the Patrick Administration and elected officials headed the MassCOSH task force’s warnings and banned the product.

While MassCOSH works hard to gather stories and data to impact change, we are a small organization with tightly stretched resources. With a staff of just eight, we operate an immigrant worker center that helps thousands of the very lowest wage workers address dire conditions from labor trafficking to wage theft to life-threatening conditions. Our youth program engages a team of 15 teen leaders in leading health and safety trainings for over 500 other teenage workers in communities of color each year. Our healthy schools initiative helps eliminate environmental hazards in schools that contribute to asthma. We also ensure that not a day goes by without an effort to educate the public that together, we can make workplace fatalities a thing of the past.

By partnering with the Boston Global Forum, MassCOSH’s impact can be magnified substantially. BGF’s dynamic network of talented, concerned and well-networked individuals can lend some strategic muscle to uphill legislative battles and help MassCOSH grow in size and influence. MassCOSH could particularly benefit from an expanded pool of business allies who see regulations as life-savers and not needless and expensive excess that would only “hurt profits.” Together, we can and will save lives.

by Admin | Sep 15, 2013 | News

Country Manager, Bangladesh Impactt