by Admin | Apr 2, 2014 | News

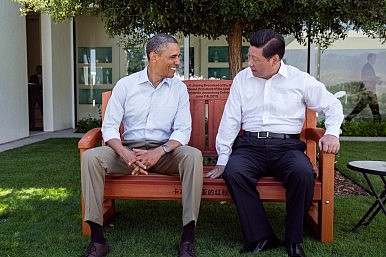

(Photo Credit: Flickr/US Department of State)

(BGF) – In this article, featured in The Diplomat, Jin Kai addresses the challenges facing the U.S. effort to reinvent its relations with China. Kai notes that Max Baucus, the new U.S. Ambassador to China, strives to “strengthen economic ties with China, to be a partner with China to tackle common global challenges, and to do everything possible to promote stronger people-to-people ties.” While this is all fine and well, Kai notes, echoing a similar point made by Shannon Tiezzi, that the lack of trust and political will present key issues to the improvement of U.S.-Chinese relations. An excerpt of the article is provided below. To read the full article click here or visit The Diplomat‘s website.

Reinventing US-China Relations: Mission Plausible?

By Jin Kai

In his first press conference in Beijing, the new U.S. Ambassador to China Max Baucus said he has three goals: to strengthen economic ties with China, to be a partner with China to tackle common global challenges, and to do everything possible to promote stronger people-to-people ties.

Beyond all doubt, these have been the most important jobs for all U.S. ambassadors to China during the past few decades. In particular, both Baucus and his predecessor, Gary Locke, highlighted strengthening economic ties with China as their top priority. This seems to be telling the world that these two leading economies might just find their way out of the potential doom awaiting two rival great powers. They seek to make this great escape through the type of grand and comprehensive approaches that have been talked up and stereotyped repeatedly, although such strategies are indeed very important.

But there is a problem. Based on their respective strategic perceptions, it is obvious that there is no genuine mutual trust between China and the U.S. So, is there any mechanism for China and the U.S. to try to build a minimum level mutual trust at least on strategically important issues? There seems to be an important one. Five rounds of Sino-U.S. Strategic and Economic Dialogues have been held since 2009, but true Sino-U.S. mutual trust is still nowhere to see. Rather, these two giants seem to be tangled with each other in a“Thucydidean trap” or a “prisoner’s dilemma.” Issues that could have made China and the U.S. join hands or at least might have helped them reach a mutual understanding instead turn out to be potential flashpoints or excuses for reciprocal accusations. One such issue is cybersecurity, which has heightened distrust between Chin and the U.S. in recent days after media reports said that the NSA “put considerable efforts into spying on Chinese politicians and firms.” Are these two giants ready to be entangled in a cyber-war?

The consequences of a Sino-U.S. violent conflict are unacceptable and unbearable not only for China and the U.S., but also for the rest of the world. China-U.S. economic ties are already very close and these two economies can hardly find an easy way to depart from each other. However, on many regional and global issues, these two powers still hold very different views and positions. As a result, their partnership is simply no more than diplomatic rhetoric so far.

People-to-people exchanges, one of Baucus’ goals, is a reasonable and profitable approach to enhancing mutual understanding and improving bilateral relations. Such exchanges may bring about far-reaching and profound changes to future China-U.S. relations. However, given the regional and world situation and especially the possibility of intensifying Sino-U.S. distrust, it’s better to get to the point and make changes happen quickly. The puzzle of closer economic ties accompanied by deeper distrust must be changed.

On March 18, former U.S. Ambassador to China Jon Huntsman made a comment in Shanghai on China-U.S. relations in the context of the search for Flight MH370. He pointed out that both countries have the capability, but what is missing is coordination. To go a little further, the current China-U.S. relationship as a whole may be evaluated in the following three categories: capability, coordination, and political will.

Click here to continue reading.

by Admin | Apr 3, 2014 | News

(Photo Credit: REUTERS/Tyrone Siu)

(BGF) – Earlier this year the Chinese Foreign Minister, Fu Ying, remarked that China’s relationship with Japan was “at its worst”. Taking that statement as his starting point Ian Bremmer analyzes China and Japan’s current relationship, the likelihood of conflict, and the prospects for de-escalating the tensions between these two countries. As Bremmer notes, neither China nor Japan want to engage the other in armed conflict. However, this, Bremmer argues, may lead both countries to push the envelope knowing that the other would not dare to instigate a conflict. This is particularly the case given that the tense relationship has become an outlet for nationalist pressures in China and Japan. While Bremmer feels that conflict between China and Japan is unlikely, it is possible that we will face longer periods of tension between the two countries.To read the full article click here or visit the Reuters website.

Is the China-Japan relationship ‘at its worst’?

By Ian Bremmer

At the Munich Security Conference last month, Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Fu Ying said the China-Japan relationship is “at its worst.” But that’s not the most colorful statement explaining, and contributing to, China-Japan tensions of late.

At Davos, a member of the Chinese delegation referred to Shinzo Abe and Kim Jong Un as “troublemakers,” lumping the Japanese prime minister together with the volatile young leader of a regime shunned by the international community. Abe, in turn, painted China as militaristic and overly aggressive, explaining how — like Germany and Britain on the cusp of World War One — China and Japan are economically integrated, but strategically divorced. Even J.K. Rowling has played her part in recent weeks, with China’s and Japan’s ambassadors to Britain each referring to the other country as a villain from Harry Potter.

Of course, actions speak louder than words — and there’s been no shortage of provocative moves on either side. In November, Beijing declared an East Asian Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) — which requires all aircraft to follow instructions issued by Chinese authorities, even over contested territory, which pushed tensions to new highs. The following month, Abe visited Yasukuni Shrine — a site associated with Japanese World War militarism that makes it an automatic lightning rod for anti-Japanese sentiment among Japan’s neighbors.

But despite the clashes and growing conflict, it remains exceedingly unlikely that China-Japan fallout will escalate into military engagement. China won’t completely undermine economic relations with Japan; at the provincial level, Chinese officials are much more interested in attracting Japanese investment. And Japan still sees the success of its businesses in the vast Chinese market as an essential part of efforts to revive its own domestic economy, even if its companies are actively hedging their bets by shifting investment away from China. The relationship is unlikely to reach a boiling point. Rather, we are more likely to see sustained cycles of tension.

So if both sides intend to limit the potential for conflict, how concerned should we be? Even if military engagement is highly unlikely, China-Japan is still the world’s most geopolitically dangerous bilateral relationship and that will remain the case. There are a number of reasons why.

First and foremost, there’s always the chance, even if it’s remote, for miscalculation with major consequences. When fighter jets are routinely being scrambled to deal with Chinese “incursions” into what the Japanese consider to be their territory, the potential for a mistake looms large. And given the frigid relations between these two countries, if there is a mistake, China and Japan are going to assume the worst of the other side’s intentions.

On top of this, the sheer size and integration of the economies — China and Japan are the world’s second and third-largest economies, respectively — makes the relationship hard to ignore. Japan has 23,000 companies operating in China, with 10 million Chinese workers on their payrolls. But Japanese companies are actively diversifying away from China now, with foreign direct investment waning and Japan shifting to Southeast Asia in particular. China-South Korea trade is fast approaching the levels of China-Japan trade as a result of fallout from tensions between Tokyo and Beijing. If the Chinese and Japanese start thinking their economic relationship is deteriorating, the potential for confrontation grows.

Furthermore, the size and duration of the conflict makes it a crucial global risk: the tensions are rooted in historical animosity with no viable solution. There’s no diplomatic outreach going on between China and Japan — and neither the United States nor any other foreign power is doing enough to help facilitate that relationship. There is no one in China trying to see the world from Japan’s perspective, and vice versa. According to a recent Pew Research poll, just 6 percent of Chinese had a favorable view of Japan, and only 5 percent of Japanese view China favorably. Both sides may be well aware that a full-fledged conflict is not in the other’s best interest — but that only gives them more reason to push the envelope. As a senior Chinese official recently explained to me, the Chinese aren’t worried about pushing Japan (they “don’t want war” and the Japanese “don’t dare”).

Click here to continue reading.

by Admin | Mar 31, 2014 | News

(Photo Credit: MARK RALSTON/RIE ISHII/AFP/Getty Images)

(BGF) – In this article, featured in The Globalist, J.D. Bindenagel looks to Europe in 1914 in an attempt to distill lessons for Chinese-Japanese relations. As Bindenagel notes, the outbreak of WWI demonstrated that economic and trade ties alone cannot necessarily prevent the onset of war and conflict. Thus, in order to avoid conflict China and Japan must find a way to “turn enmity in amity”. Bindenagel then provides four potential steps that can taken to successfully manage the tensions between Japan and China. The article can be viewed below as well as on The Globalist’s website.

(Photo Credit: MARK RALSTON/RIE ISHII/AFP/Getty Images)

(BGF) – In this article, featured in The Globalist, J.D. Bindenagel looks to Europe in 1914 in an attempt to distill lessons for Chinese-Japanese relations. As Bindenagel notes, the outbreak of WWI demonstrated that economic and trade ties alone cannot necessarily prevent the onset of war and conflict. Thus, in order to avoid conflict China and Japan must find a way to “turn enmity in amity”. Bindenagel then provides four potential steps that can taken to successfully manage the tensions between Japan and China. The article can be viewed below as well as on The Globalist’s website.

Europe 1914: Lessons for China and Japan in 2014

By J.D. Bindenagel

Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe recently likened the tensions between Japan and China to the relationship between Germany as a rising power challenging the United Kingdom 100 years ago. He certainly had a point when he noted that trading relations and investments had not stopped the brewing conflict in Europe a century ago from engulfing the world in war.

It is ominous that China and Japan are currently so keen on butting heads. After all, this is 2014. People throughout Asia must nervously reflect on the hard lessons the Europeans learned.

Europeans are revisiting the Great War on the 100th anniversary of its outbreak in August 1914 after Gavrilo Princip, a local terrorist in Serbia, not one of the major belligerent countries, assassinated the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and launched a global war. The failure of European leadership a century ago brought calamity to Europe.

Domino-style, that war brought on a veritable tumbling of major empires, beginning with that led by the Russian Tsar, the Austro-Hungarians and the Ottomans. It also destroyed the foundations of the global economy and European governance. Fascism and dictatorship followed in the 1930s that led to the Second World War and the Cold War.

In East Asia leaders can consider these lessons, remember that economic relations offer no guarantee that rising powers will rise peacefully and prevent the world from sleepwalking into war.

The real challenge, whether then in Europe or now in Asia, is how to turn enmity into amity. Then as now, the best way to proceed is to begin with small steps in the resolution of many disputes. And this is where Japan’s Prime Minister must do much more than (implicitly) point the finger at China.

There is no denying that China suffered humiliation from the Japanese Imperial Army invasion in the Sino-Japanese Wars. Little wonder, given the absence of an apology from Japan, that the Second World War continues to feed Chinese anger.

This is part of the sentiments that are surfacing in thecompeting claims for the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea. The lack of recognition of the wartime conquest of Nanjing and Prime Minister Abe’s visit to the controversial Yasukuni shrine remain significant symbols of lack of justice for China.

Unlike the cultural context of Europe that respects apologies that accept responsibility for suffering brought on by the National Socialist regime in the Germany of World War II, Japan and China seem caught in a cultural context where shame is associated with apology.

German President Johannes Rau apologized to the victims of Nazi Germany in 1999, which was respected by the millions of living victims who suffered in the name of the German people. Unfortunately, reconciliation from the bitter events of the Second World War would be ideal, but resolution of all these issues is not likely.

There are several steps that can be taken to successfully manage these tensions:

1. Chinese, Japanese and regional leaders should set aside the use of force to resolve the tension. A code of conduct in the South China Sea is necessary to manage maritime operations.

2. the parties should engage with each other in clarifying narrative to promote mutual understanding and prevent angry populisms and xenophobic nationalism that can rebound to destroy leaders and countries.

3. Japan, China, Vietnam should set aside the unresolved issues and turn to joint management of national interests in fishing, energy and resource development. The Gulf of Tonkin-Hainan agreement between China and Vietnam is one example.

4. The United States should provide needed leadership among parties to create and share historical narratives that can lead to better understanding, maritime policing, adherence to the Law of the Sea and maintenance of the freedom of the seas for shipping, while helping to avoid political miscalculation and military confrontation.

Click here to view the article on The Globalist.

by Admin | Mar 29, 2014 | News

(Photo Credit: Flickr/The White House)

(BGF) – Often, the current relationship between the U.S. and China is viewed as a Thucydidean Trap – essentially a struggle for power between two powers. In this article Shannon Tiezzi looks back at the U.S.-Chinese diplomacy and rhetoric and challenges the view that U.S.-Chinese relations is a Thucydidean Trap. Rather, Tiezzi contends that the current U.S.-Chinese relations are best conceptualized as a Prisoner’s Dilemma. Tiezzi argues that U.S. and Chinese leaders recognize the importance of collaboration and cooperation between the two powers. However, forewshadowing what Kai would later write in The Diplomat there is a deep sense of distrust between the U.S. and China. Thus, both the U.S. and China fear that the other will not follow through on its commitments to cooperate. As a result, neither side wants to be “left holding the bag when the other side inevitably turns hostile.” Therefore, it appears that a lack of trust between the U.S. and China is holding back U.S.-Chinese relations. An excerpt of the article is included below. Click here to read the full article or visit The Diplomat‘s website.

US-China Relations: Thucydidean Trap or Prisoner’s Dilemma?

By Shannon Tiezzi

U.S.-China relations are at a crossroads. China, now the number two economy in the world (and, depending on who you ask, projected to pass the U.S. as number one in 2016, 2020, 2028, or not at all), has a growing political and military clout commensurate with its economic prowess. Accordingly, China has a strategy for achieving a long-time goal: gaining control of its near seas, at least out to the so-called “first island chain.” The U.S., for its part, is loathe to cede its role as the dominant power in the Asia-Pacific, especially given its alliance relationships with many of China’s close neighbors (including South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Thailand, and, unofficially of course, Taiwan).

But the issue of military or diplomatic dominance in the Asia-Pacific is merely a microcosm of the greater challenge: finding a balance of power between the U.S. and China that is acceptable to both nations. Many analysts have framed this dilemma as the “Thucydidean trap” that arises each time a rising power challenges as established one. To try and escape this historical trap (which has generally led to war), China’s leaders have proposed that China and the U.S. seek a “new type of great power relationship.” But what does this actually mean?

At one meeting between the U.S. and Chinese presidents, there were plenty of ideas on how the U.S. and China could work together. According to the American president, “China and the United States share a profound interest in a stable, prosperous, open Asia” so cooperation on the issue of North Korea’s nuclear program is a must. There’s also a need “to strengthen contacts between our militaries, including through a maritime agreement, to decrease the chances of miscalculation and increase America’s ties to a new generation of China’s military leaders.”

On a global front, “the United States and China share a strong interest in stopping the spread of weapons of mass destruction and other sophisticated weaponry in unstable regions and rogue states, notably Iran.” In addition, there is “the special responsibility our nations bear, as the top two emitters of greenhouse gases, to lead in finding a global solution to the global problem of climate change.”

And the Chinese president offers a broader assessment of what U.S.-China relations should look like: “It is imperative to handle China-U.S. relations and properly address our differences in accordance with the principles of mutual respect, noninterference in each other’s internal affairs, equality, and mutual benefit.”

The above are solid (if vague) proposals that offer a blueprint for moving U.S.-China relations forward. But hold on—those quotes weren’t from President Barack Obama and President Xi Jinping. The speakers were President Bill Clinton and President Jiang Zemin during a press conference in 1997. 17 years later, in 2014, these same issues are still being hashed over and trotted out as areas for improvement. Despite a mind-boggling proliferation in high-level meetings, Beijing and Washington have made little progress on the very issues they’ve been highlighting as areas of cooperation for nearly 20 years. Outside of a steady increase in bilateral trade, have U.S.-China relations really progressed since the 1990s? And if not, how can Beijing and Washington be expected to draw closer now, when the competition between the two is even greater?

Forget the “Thucydidean trap”—China and the U.S. are caught in the foreign policy version of the “prisoners’ dilemma.” Both understand, on a theoretical level, that the best outcome can only be reached via cooperation. But neither country trusts the other to cooperate (for reasons outlined in detail in a report by Brookings’ Kenneth Lieberthal and Peking University’s Wang Jisi). Both sides can “win” through cooperation, but since neither Beijing nor Washington really believes that will happen, they both seek not to be the country left holding the bag when the other side inevitably turns hostile.

Click here to continue reading.

by Admin | Mar 26, 2014 | News

(Photo Credit: Reuters)

(BGF) – Recently BU Today published an article by Thomas U. Berger, Associate Professor of International relations at Boston University. In this article Professor Berger discussed the U.S.-Japanese security relationship and China’s increasingly bold actions in the South China Sea. As Professor Berger notes in the article, China’s aggressive maneuvers in East Asia have put a strain on the U.S.-Japanese security relationship. For example, the U.S. reaffirmed its commitment to its security pact with Japan, but only did so orally rather than in writing. This raised some concern in Japan. This comes at a time when Japan feels it is particularly vulnerable to threats from its neighbors. Japan, for its part, has experienced a resurgence of nationalist political leaders who have emerged in the face of the threat from its neighbors. Japan’s resurgence of nationalist political leaders have further exacerbated regional tensions. While the economic interdependence between Japan and China make conflict unlikely, Professor Berger argues that the U.S. must increase its support for Japan in order to prevent Japan from undertaking bold actions that could incite further conflict. Ideally, renewed support could encourage Japan to pursue diplomatic resolutions with its neighbors. Otherwise, Obama’s pivot to Asia could be in peril. To read the full article click here or visit the BU Today website.

POV: Obama’s Asian Pivot in Peril?

By Thomas U. Berger

The American-Japanese security relationship has been the cornerstone of US strategy in East Asia for more than half a century. The Obama administration’s “pivot to Asia,” a multipronged effort to keep the United States active in Asian affairs, depends on keeping that relationship strong. Yet while the two countries are investing considerable effort in strengthening ties, there are signs of growing strain. Left unattended, there is a serious and growing risk of a crisis and even a rupture.

Take the “2+2” meeting held in Tokyo last October, where the two governments began revising the guidelines governing defense cooperation between their military forces. They made progress in underlining their continued solidarity and work toward a closer cooperation to meet new security threats: a nuclear-armed North Korea and a more assertive China. But ambivalence was clear.

While Japan may move toward removing some of the legal barriers to closer cooperation, it wants to avoid becoming too entangled in broader US strategic designs. For its part, the United States offered only lukewarm support on the disputed Senkaku-Diaoyu Islands, which are under Japanese control, but are claimed by China. The US reaffirmed orally that if the islands were attacked, it was bound by the terms of its alliance with Japan to come to its aid, but declined to do so in writing, to the disappointment of some in Tokyo.

Past disputes between the United States and Japan didn’t negate the sense that their strategic interests were in substantial agreement. This time, that is being questioned. North Korean nuclear armament and China’s rise have led to a much higher level of threat perception on the part of the Japanese public than at any point since the end of World War II. Although the Soviet Union had far greater military capabilities, the possibility that Japan would be directly threatened seemed remote. Today’s repeated outbreaks of virulent anti-Japanese sentiments—including riots and mass demonstrations—in Beijing and Pyongyang, even in fellow US ally Seoul, has convinced many Japanese that in the event of a conflict, their closest neighbors are capable and eager to attack them. The Chinese-Japanese standoff over the uninhabited Senkaku-Diaoyu Islands and a less militarized dispute with South Korea over the Dokdo-Takeshima Islands reinforce Japanese fears.

This growing sense of threat has encouraged the reemergence of strongly nationalist political leaders, including Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who holds revisionist views on Japan’s World War II-era atrocities that are profoundly offensive to Japan’s Asian neighbors. In a potentially vicious cycle, Japan’s resurgent conservative nationalism alarms its neighbors and feeds anti-Japanese sentiments, leading to a greater sense of threat in Japan and a greater readiness to support nationalist politicians. Washington views this with a mixture of trepidation and despair. It seems inconceivable, given the high level of economic interdependence between Japan and its neighbors and the limited strategic value of the disputed territories, that Japan and China would risk a conflict. Yet political realities in Tokyo and Beijing (and Seoul) have locked the sides into a belligerent stance on the disputed islands that sooner or later could lead to a disastrous conflict.

Washington bears some blame for its tensions with Japan. Its position on the territorial disputes is that such disputes be handled peacefully, according to international law. This legalistic position raises suspicions on all sides. Beijing suspects that the United States is trying to encourage the dispute to more firmly embed Japan into an anti-Chinese coalition. In Tokyo, our refusal to commit more fully raises doubts about our reliability in a crisis.

The United States may judge it has little choice but to carry on with its current policies. Revising Japan-US defense cooperation guidelines sends a strong message to Beijing that aggression is intolerable. It reassures the Japanese that the United States will stand by them in a crunch and may discourage Abe from taking a harder-line stance. At the same time, by not taking a position on the territorial issues, Washington warns Japan that its support should not be interpreted as a carte blanche to be more aggressive about history or other sensitive issues, and leaves open the possibility for constructive dialogue with Beijing.

Click here to continue reading

by Admin | Mar 28, 2014 | News

(BGF) – In this article, J.D. Bindenagel assesses Russia’s actions in the Ukraine through the lens of Putin’s experience in East Germany in 1989. During his time as KGB officer, Putin was stationed in East Germany during the German democratic revolution that ultimately led to Germany’s reunification. Bindenagel argues Putin’s experiences in East Germany, particularly witnessing the fall of Soviet rule in East Germany due to democratic street protests, has carried over to his stance on the Ukraine. Thus, we must understand Russia’s incursion into the Ukraine as a geopolitical move based on Putin’s past experience. An excerpt from the article is included below. Click here to read the full article or visit The Globalist‘s website.

Putin’s Russia Reset: What Putin learned from the 1989 German revolution — and how he misunderstood it

By J.D. Bindenagel

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin is a heavily traumatized man. Despite all the air of invincibility he is constantly trying to project to the world, the events in Ukraine ring home to him in a very personal manner.

In fact, Putin has seen this movie – a major ally falling, even though that country was decked out with leaders fully supportive of Russia’s cause – before.

What are the Maidan and the streets of Kiev now were the streets of East Germany back in 1989 – with one big difference: Putin himself was an operative in that battle against freedom.

Lt. Colonel Putin, who spent the 1980s as a KGB officer, had arrived as a near-omnipotent man in East Germany. His Angelikastrasse Villa in Dresden, Putin’s house as the local chief KGB resident, was located directly across the street from what was then the East German secret police, Stasi, headquarters in town.

From this perch, he witnessed a course of events in East Germany that he couldn’t stop from unfolding.

Before long, in August 1994, a once high and mighty Russia simply had to pick up and leave Germany, tail in hand. No doubt these events humbled and shamed him.

Decades later – on Tuesday, March 18, 2014 – and as if to gloss over all over that, Putin tried to be cute. In announcing the annexation of Crimea, he sought to equate it with German reunification and, given that context, asked the Germans to support it. They didn’t take the bait. Chancellor Merkel’s spokesman immediately rejected Putin’s proposition.

Putin thus tried to cast Crimea’s return into Russia’s web as a case akin to when the then-Soviet Union had supported German reunification in 1990.

The Sochi Games – to make shame undone

As part of the campaign for the shame he felt all along from the events of 1989/1990, which he has always perceived as the unnecessary self-diminution of Russia, Putin orchestrated the Sochi Olympic Games. His overarching goal was to celebrate the “new Russia” in the spring of 2014.

Alas, his costly “strategic” planning quickly came to naught. The Sochi Games now resemble an effort to put glossy red lipstick onto the face of the same old Soviet style of operations.

To Putin’s eternal chagrin, the “Ukrainian Street,” with its unbending demonstrations in Kiev, brought down the Russian-sponsored Communist government — and prompted Russia’s occupation of Crimea.

Doubly traumatized

That “his” Olympic Games were double-crossed by a chain of events that remarkably resembles the events Putin had witnessed in East Germany from his Dresden perch in the fall of 1989 was simply too much.

In September 1989, demonstrators in Putin’s Dresden neighborhood took to the streets and demanded freedom.

To add insult to injury, the East German demonstrators were encouraged by then-Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. To his eternal credit, he was pursuing new thinking in the Soviet Union to transform and revitalize the Soviet Union through economic restructuring (Perestroika) and openness (Glasnost).

Even though East Germany’s leader, Erich Honecker, rejected Gorbachev’s message, Gorbachev championed the new path and warned that those who came too late would be punished by history.

The East German Street in action

On Saturday, October 7, 1989, just over a month before the collapse of the Wall, East Germany celebrated its 40th anniversary with a massive torchlight parade down Berlin’s main boulevard Unter den Linden, followed by a gala dinner in thePalast der Republik with leaders from the Communist world. President Gorbachev returned to Moscow immediately following the dinner.

That night, as soon as the celebration had ended, the crackdown began. Demonstrators had gathered at theGethsemane Church in Berlin to appeal for the release of political prisoners, freedom to travel and adherence to the Helsinki Final Act guaranteeing human rights.

Around 10 p.m., they were answered by hundreds of police swooping down the streets beating and arresting more than 1,000 demonstrators.

The next day, on Sunday, demonstrators in Leipzig prepared for the by then usual Monday demonstration. Honecker also prepared — to end the counter-revolution in the streets.

East German police were stationed in Leipzig, medical doctors’ leaves were suddenly cancelled and blood supplies ordered. The press was banned from the city and the stage was set for confrontation and bloodshed.

Gorbachev’s East German supporters, notably Hans Modrow, the last communist prime minister in East Germany, saw the dilemma. If the use of force crushed the demonstrators, it would also end Glasnost and Perestroika.

Ridding oneself of Russia

That Monday, October 9, a small group of Leipzig civic and communist leaders convened and agreed to avoid violence. The renowned Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra conductor Kurt Masur called for no violence (“Keine Gewalt”) from the demonstrators.

The Leipzig police chief issued the same order to the police.

Demonstrators met at the Nicholaikirche for Pastor Christian Fuehrer’s peace vigil — and that night, 70,000 took to the streets, marching the Leipzig ring road in protest against their Communist government. Violence was avoided.

Days later East German leader Erich Honecker was deposed and on November 9 the Berlin Wall fell. In a few months East Germany ceased to exist.

Undoubtedly traumatized by the events, Putin has had plenty of opportunity to think about the course of events at the time.

He has obviously drawn lessons from his own experience during these months of the democratic revolution in Germany. Putin recalled an incident during the 1989 revolution in Dresden when a mass demonstration aimed at the Stasi office across the street from his residence.

Putin threatened to shoot — in Germany

After the crowd ransacked the Stasi office and then prepared to storm Putin’s building, he called in the Soviet military for protection, told the crowd in fluent German that the property was Soviet territory, and threatened to shoot trespassers. The crowd dispersed.

Gorbachev may have intended to revitalize the Soviet Union, but he failed to use force when he had 380,000 soldiers in East Germany to maintain Soviet rule.

It was a terrible thing to witness for Vladimir Putin, the judo fighter, to see a repeat of this strife for freedom now unroll on the streets of Kiev under his rule.

Worse, Kiev is not Berlin or Leipzig. It is much closer to home. One may have been the “forward” buffer, but Ukraine is essential for Russia and its hyper-security mindedness.

No question on Putin’s mind whatsoever that these street protests are the greatest threat to the Russian Federation yet — and must be stopped. And so it was that democratic demonstrations in the streets of Leipzig and Berlin brought down governments.

Crimea as a consolation prize

Seizing Crimea, at most, is a consolation prize. For that reason, the world has to count on a stealthy, if not overt campaign to destabilize Ukraine further, to make sure it remains, in whatever form, in Russia’s orbit.

Why is this so essential? Because letting it happen yet again isn’t “just” about reliving the East German experience. Kiev’s real precursor is in the streets of Moscow, topped by the last great hurrah – the August Coup in 1991 against President Gorbachev.

Coup plotters and hardline Communist Party leaders opposed both Gorbachev’s new thinking as well as the “Union of Sovereign States Treaty” that Gorbachev sought to avoid the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Click here to read the full article.

by Admin | Mar 25, 2014 | Event Updates

Professor Stephen Walt with Nguyen Anh Tuan, Co-Founder and Editor-in-Chief of the Boston Global Forum.

By Philip Hamilton

(BGF) – The dispute between Russia and Ukraine is currently the focus of extensive international debate. In an effort to clarify the reasons for Russia’s incursion into the Crimea region of Ukraine, as well as propose potential solutions to the conflict, Professor Stephen Walt, the Robert and Renee Belfer Professor of International Affairs at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, gave a talk on the situation in Ukraine at the Harvard Club.

A key to unraveling the current conflict between Russia and Ukraine in Crimea is understanding the reasons for Russia’s actions in the region. According to Professor Walt, the current situation in the Ukraine is rooted in Russia’s history. Historically, Russia has been invaded on numerous occasions, including by Napoleon, Germany in World War I, and then again by Germany in World War II. These experiences have led Russia to have a heightened sensitivity to the actions of its neighbors. What is more, Russia has long felt that the U.S. has advocated the steady movement of western institutions into its sphere of influence, especially following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Russia’s history of being invaded, its subsequent sensitivity to its neighbors, and its perception that the U.S. is moving western institutions further eastward towards Russia has led Russia to take, what are at times, extreme defensive actions. In particular, Professor Walt cites the Russian invasion of Georgia, which he argues was ultimately Russia’s way of sending a message that further eastward expansion by NATO was something Russia would resist by any means necessary.

How does this play into the current situation in Ukraine? Professor Walt argues that we need to recognize these historical antecedents and conceptualize the situation in Ukraine as a geopolitical conflict. Russia’s actions are not motivated by economic strategies or even domestic political pressures. Rather, Russia’s recent actions in Ukraine are a defensive reaction.

Looking back to the origin of the Ukrainian uprisings, Professor Walt noted: “there was an EU economic plan which Putin didn’t like so he upped the ante by offering Yanukovych, it’s previous leader, a better deal: more money, fewer terms, etcetera and probably leaned on him in some other ways. Yanukovych then essentially erased the EU plan, took the Russian plan, and that was one of many things, including his own incompetence and corruption, that started the uprisings against him in Ukraine.” The U.S. response to the Ukrainian uprisings, however, did not help ease the tensions in the region. Rather, the U.S. clearly favored the demonstrators thereby reinforcing the perception in Moscow that the U.S. was trying to shape events in the region. Thus, in reaction, Russia utilized the means it viewed as necessary to exert control in Ukraine and stave off western intrusions in its sphere of influence.

Moving forward, Professor Walt is not optimistic that the conflict will be resolved. However, he made two suggestions for how the U.S. should handle the conflict. Firstly, he proposed that the U.S. defend Ukraine’s territorial integrity. Ideally this would include Crimea but he does not feel that including Crimea is absolutely necessary. Importantly, U.S. efforts to defend the territorial integrity of Ukraine should discourage further Russian incursions in Eastern Ukraine.

Secondly, Professor Walt suggested that the U.S. re-establish Ukraine’s neutrality. In essence, this means that “Ukraine will be a buffer state between east and west – it will not become part of NATO, it might at some point down the road have an association with the European Union…it will not be part of the Russian sphere of influence, it will not be part of our sphere of influence.” Using Ukraine as a neutral buffer zone between the east and west is “better for us, it’s ultimately better for the Ukrainians because if they start heading towards the west Russia will do lots of things to hurt them, and ultimately that’s better for Russia because dividing up Ukraine will be a source of much trouble between us and the Russians.” Furthermore, the U.S. may even want to go so far as to provide reassurances to Russia that the U.S. is not currently attempting, nor will it attempt in the future, to incorporate Ukraine into the west.

In many ways, the current conflict between Ukraine and Russia is difficult for the U.S. The U.S. does not have an extensive history of being invaded. However, Professor Walt argues that the U.S. must make some effort to empathize with Russia, even if it does not fully understand and certainly does not support Russia’s actions: “They, the Russians, have a view of how we got into this and what’s at stake and we’re not showing any sort of empathy for what they’re doing – we don’t have to like what they’ve done but we at least ought to be trying to understand what their view of it is.”

Additionally, Russia has a much deeper interest in what happens in Ukraine. Thus, the U.S. and Europe must be aware of Russia’s commitment to this conflict because Russia is willing to pay a much higher price to get what it wants in the Ukraine than the U.S. or Europe. In fact, the failure of the U.S. to realize that Russia would react in the manner it has to the events in Ukraine is a significant failure. However, despite the fact that Russia may have a deeper interest in what happens in Ukraine, the U.S. must not accept a scenario in which Ukraine falls under Russia’s influence to a point where Ukraine is barred by Russia from having economic relations with the U.S. and Europe – that would be an entirely unacceptable scenario.

While the U.S. and Russia are at odds over the conflict in Ukraine, Professor Walt emphasizes that we must not let the relations between the U.S. and Russia deteriorate to the point where they cannot agree on key issues such as Iran, Syria, and China. Efforts must be made to find the minimum requirements necessary to satisfy both the U.S. and Russia in order to resolve the conflict in Ukraine and salvage the U.S.-Russian relationship. Although the U.S. may have failed to adequately understand and anticipate Russia’s reaction to the situation in Ukraine, the understanding provided by Professor Walt can certainly go a long way towards guiding the U.S. policy regarding the conflict in Ukraine going forward.

by Admin | Mar 22, 2014 | News

(Photo Credit: AP)

(BGF) – In this article featured in The New York Times, by Hugh White, addresses three policy options facing the U.S. regarding China’s aggression in East Asia. The first option would be for the U.S. to follow through on its agreement to defend Japan in the event that the tensions between China and Japan escalate into conflict. This option could embroil the U.S. in a war which it would have little control over. The second option would be for the U.S. to back out of its commitment to defend Japan, thereby leaving Japan to fend for itself. While this would avoid U.S. involvement in the war, it would greatly diminish the U.S.’s influence in Asia. The third option, which White endorses, is for the U.S. and China to reach an agreement in which the U.S grants China greater control in East Asia in exchange for China’s commitment to pursue its goals without aggression or the threat of force. Ultimately, this would require the U.S. and China to learn to share power, and more importantly, for China to learn to negotiate with its East Asian neighbors. An excerpt from the article is included below. Click here to read the full article.

Sharing Power With China

By Hugh White

CANBERRA, Australia — For 40 years American leadership has kept Asia stable and fostered economic growth, especially in China. But today China’s growing power is undermining that old order and posing big questions about America’s future role in the region.

Those questions loom in the ongoing dispute between China and Japan over a chain of tiny uninhabited islands in the East China Sea that could easily spark an armed clash between the two rivals. Such a conflict would escalate fast, and the United States would have to quickly take action to support Japan militarily against China — or not.

Washington remains neutral on who owns the islands, while criticizing China for using displays of force to challenge Japan’s de facto control of them. As Secretary of State John Kerry has said: “The United States, as everybody knows, does not take a position on the ultimate sovereignty of the islands. But we do recognize that they are under the administration of Japan.”

American officials have also affirmed support for Japan as an ally under the United States-Japan defense treaty. But it’s clear that Beijing doesn’t buy that. Instead, China has concluded America would stand back in an armed conflict, which is why it increasingly courts confrontation with Japan so brazenly. China’s ships and aircraft regularly patrol in areas claimed by Japan. Beijing’s declaration late last year of an air defense zone covering the islands took the confrontation to a new level.

Only a formal and explicit statement from President Obama laying out a new American policy will reduce the risk of a crisis in the East China Sea. What should Mr. Obama say?

If America makes it clear it would not support Japan in a fight with China, Tokyo’s confidence in the alliance will be shattered. Japan would then face its own choice: Rearm to defend itself against China without American help or submit to Chinese pre-eminence in Asia. Other American allies would also reconsider their options. American leadership in Asia would never be the same again. This is what China hopes will happen.

But a statement of unconditional support for Japan would commit America to a potential war that it could not control and probably would not win. We cannot assume China would simply back down: It has too much at stake. China does not want a war with America, but Beijing probably believes it could force a favorable draw. Ultimately, China is just as willing to fight to change the Asian order as America is to preserve it, and perhaps more willing.

Of course there are doves as well as hawks in Beijing, but even the doves believe China should be reclaiming its place as a great power in Asia. Beijing no longer thinks that American primacy is essential for the stability that China itself needs. No one in China, not even the more liberal-minded officials, believes that it’s their destiny to submit to American leadership indefinitely.

When both of America’s options are so bad, it is not surprising that the Obama administration finds it hard to articulate a clear policy. That is why Washington’s signals have been mixed, with the president remaining silent.

The fact is that, for America, these East China Sea islands, called Senkaku in Japanese and Diaoyu in Chinese, are not worth a fight with China. Still, preserving the American alliance with Japan, its regional leadership role and the whole Asian status quo are vital United States interests.

There is a third way. An American policy not to fight for the status quo does not have to lead inevitably to Chinese hegemony in Asia. A new Asian security arrangement could be forged in which America concedes a larger share of leadership to China but remains engaged to balance and limit Chinese power and help uphold key norms — including the all-important norm against the use or threat of force to settle disputes.

Ultimately this norm is more important than any particular alliance. It is the foundation of America’s post-1945 vision of international order. Washington should worry more about China’s willingness to defy this norm in the East China Sea than about its determination to challenge the United States-Japan alliance and change the regional order. America should be willing to fight China to protect that norm. This makes Washington’s choice a little clearer.

Mr. Obama should say that he is willing to negotiate a new security arrangement in Asia that accords China a bigger share of regional leadership, but only if China forgoes the use or threat of force to compel such changes.

If China persists in threatening the use of force, then America should be willing to fight, and must say so clearly. If China is prepared to desist, then America should be willing to talk about sharing power, and it should say that clearly, too.

We cannot know exactly how this kind of regional power-sharing would work. It would have to be negotiated with China and with the region’s other great powers. The best historical template might be the Concert of Europe that kept the peace in Europe for the 100 years until 1914 — based on principles of equality and power-sharing among the big players.

Like Europe then, Asia today needs a new arrangement in which no country has a unique leading role, and all the great powers agree not to seek primacy over the others. All the big regional questions would then have to be settled by negotiation between equals.

It would mean a lot of give and take. For example, America might accept that China will eventually assert control over Taiwan, and in return China could accept that it cannot make a territorial claim over the whole South China Sea.

Click here to continue reading.

by Admin | Mar 21, 2014 | Boston Global Forum Awards

(BGF) – Recently BGF was fortunate to be able to sit down with Professor Robert Desimone in the latest installment of the Boston Global Forum Leader Series. Professor Desimone is the Doris and Don Berkey Professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT, Director of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, and a member of the Boston Global Forum’s Board of Thinkers. In his BGF Leader Series lecture Professor Desimone addressed the work of the McGovern Institute and recent advances in neuroscience research. He also took the time to answer questions sent in from viewers. The transcription of Professor Desimone’s BGF Lecture is provided below. A briefing of Professor Desimone’s talk is also available.

Tuan Nguyen: Welcome! I am Tuan Nguyen, Co-Founder and Editor-in-Chief of the Boston Global Forum. I am very honored to introduce Professor Robert Desimone.

Robert Desimone is the director of the McGovern Institute and the Doris and Don Berkey Professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT and a member of the Boston Global Forum’s Board of Thinkers. Prior to joining the McGovern Institute in 2004, he was director of the Intramural Research Program at the National Institutes of Mental Health, the largest mental health research center in the world. He is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a recipient of numerous awards, including the Troland Prize of the National Academy of Sciences, and the Golden Brain Award of the Minerva Foundation.

Governor Michael Dukakis, Chairman of Boston Global Forum visited the McGovern Institute on December 12, 2013. He is very impressed and has a high respect for the achievements of the McGovern Institute and Professor Robert Desimone. He and Kitty Dukakis will visit the Institute again in late April 2014. Today Chairman Michael Dukakis and Kitty Dukakis are in Los Angeles, they send their warmest regards to Professor Robert Desimone and the McGovern Institute for Brain Research.

Boston Global Forum will recognize and honor the McGovern Institute’s research achievements and Edward M. Scolnick Prize in Neuroscience in the Boston Global Archive, and at a later stage BGF will add it to the Boston Global Museum, an initiative we are working on for the future.

Today, We are very honored to present to you Professor Robert Desimone on the BGF Leader Series. Thank you so much. Now, Professor Robert Desimone.

Prof. Desimone: Thank you, Tuan. Thank you so much for inviting me to speak on the Boston Global Forum. I support the mission of the Boston Global Forum very much and I especially appreciate the support that Governor Dukakis and Kitty Dukakis have given over the years to brain research – I’m going to talk quite a bit about that today. I’m really just delighted to part of the forum and speaking to you. I thought I would start by just giving you a little bit about my own background. When I was in college, at that time I thought I wanted to be a psychotherapist and help people in therapy suffering from mental illness. Actually, I realized that my talents were not in therapy and I actually had stronger talents in neuroscience research and so I pursued my graduate work at Princeton in neuroscience research and then went to the National Institutes of Health, particularly the National Institute of Mental Health where I was a scientist in the program and eventually became a lab head in the program pursuing my research on the neural basis of how the brain pays attention. Then, at some point, I was asked to become the head of the intramural program for the NIMH, which is the internally funded research division of the National Institute of Mental Health – it is the largest mental health research center in the world, with research ranging from mice to many clinical wards with patients ranging from children to the elderly with a great many clinicians and psychiatrists in the program. When I became responsible for the program I realized how difficult it was for our clinicians to be making progress in coming up with new treatments for the patient populations. They were incredibly committed and they were incredibly smart and hard working, but the sad fact was that the pipeline of new ideas – new drugs and so on – was really pretty dry. I foresaw that this was going to continue unless we really made more progress in understanding a lot of the fundamentals of how the brain worked so that we could develop new treatments based on this fundamental understanding of the brain and its circuits. To make progress in this fundamental research that’s when I decided I would come to MIT – I was offered to become the Director of the McGovern Institute at MIT, which was a fantastic opportunity for me.

Just a bit about the McGovern Institute. The McGovern Institute was founded in 2000 by Pat and Lore McGovern at MIT. Over the years we have put together a team of faculty members that now includes 19 faculty members whose research ranges from basic mechanisms of genetics and neural development, even in worms going up through a variety of other animal species and then into human subjects where we study human cognition, health, and disease. We have many distinguished faculty members – several members of the National Academy of Science and one Nobel Prize winner, Bob Horvitz, for his work on the genetic basis of program cell death which plays a very important role in the development and ongoing operation of the brain. In retrospect, I feel that the decision to come to MIT, where we had such a strong foundation in basic research, was really the best decision I have made in my research career and my decision has really been borne out by what has happened since then. It has become clear in just the last few years that psychiatric diseases that we thought, for example, were very, very distinct from one another – schizophrenia, bipolar disease, autism, very, very distinct orders that at least appeared so from a clinical point of view – actually share many, many genes that lead to vulnerability for these disorders. Many of these genes affect how neurons communicate with each other in the brain and problems in neural communication can lead to increased vulnerability for any number of psychiatric disorders. So, focusing on the fundamentals – focusing on those commonalities, things like: how neurons communicate in the healthy brain and how can that go wrong?; how can you have miscommunication that would lead to a psychiatric disorder? – has really proven to be the best approach. Once you lay this foundation of knowledge at a basic level then you can proceed on to translational studies where you can test new treatments.

This philosophy has been adopted also by our president, President Obama, in the new BRAIN Initiative, which is focused on the development of new technology for brain research. New technology is one of those things where when you have an all-new technique – it’s like for the astronomers the invention of the telescope or for the biologist, the invention of the microscope. For the neuroscientist, putting powerful new tools in their hands is going to lead to rapid progress across the board in neuroscience research and it will surely accelerate the pace of research that will lead to new treatments for mental disease.

I thought I would use the next few minutes to tell you about some of the most exciting advances in brain research, all of them actually driven by new technology that has been developed in just the past few years. I guess I would start with sort of the prototype for how we imagine research becoming accelerated in the future, which is the cost of sequencing the genome. As many of you know, it was the human genome sequencing project that led to the sequencing of the human genome some years ago, but it was an incredibly expensive enterprise that took tremendous resources, spread across labs, and took many years to accomplish. But now the cost of sequencing has dropped so low, compared to the initial cost, that a project that initially was many millions of dollars now costs on the order of a few thousand dollars to sequence the genome of one individual. That has opened up genomic approaches to large populations. We’ve had an explosion of genetic discoveries in all areas of medicine but I would say particularly in psychiatric disorders where we have now a reasonable understanding of some of the many genes that are contributing to vulnerabilities to these disorders. Now, of course, there is no direct link between a genetic mutation and a psychiatric disorder in almost any case, only very rare cases. But the mutations can lead to increased vulnerability – so there may be some other event that happens in life, whether it’s a virus, a biological factor, an environmental stresser, many, many different factors are going to interact on a genetic basis – but together these genetic mutations can lead to this increased vulnerability and that’s fueling a host of new neuroscience studies to understand this link between a genetic vulnerability and how you ultimately end up with an abnormally functioning neural circuit and then dysfunctional behavior and once we understand those links then we can intervene with treatment. We’ve tremendously benefitted from the new technology involved in sequencing. Some of the other major advances in just the last few years include what, in neuroscience, we call optogenetics. This is one of the many tools of neuroscience that has come out of the genetic program – these are the tools of genetics. With optogenetics researchers are able to insert genetic material into neurons and make them sensitive to light. That allows the researchers to have exquisite control over the neural circuits involved in health and disease – these are in animal models so far – but have exquisite control over these neural patterns and to test our ideas about how these circuits work and how they might break down from disease. There will be clinical applications in the future. Perhaps the first will be in the treatment for blindness – there are already studies underway to put this genetic material into cells in our retina for people suffering from macular degeneration, retinitis pigmentosa, for example – that could help restore vision in these people by making some of the other neural elements in the retina sensitive to light when the photo-receptors are destroyed. I think we’ll see applications in brain stimulation and Parkinson’s Disease, perhaps depression, and so on. It has completely changed the pace of neuroscience discovery in just the last several years. Two, actually 3, of our faculty members here in the McGovern Institute played an absolutely key role in the development of optogenetics including Ed Boydon, Feng Zhang, and Guoping Feng, who are all continuing to do research, some of which involves optogenetics today.

Another major technological advance that has really impacted our research is human brain imagining in many forms. Most of it’s based on MRI machines which I’m sure most of the audience has seen pictures of these machines in magazine articles and so on; the large doughnut-shaped machines and people get inserted and then you can image the brain. Most people have seen structural images of brains that have come out of these machines but we can now image functional changes, we can track the activity patterns in the brain – at least on a coarse temporal time-scale – and you can actually see the brain at work as people solve problems, have emotions, understand situations, and so on, and its been applied now to many different patient groups to try to track down sources of abnormal neural circuits. In just the next few years I think that this new brain imaging technology will be paired with these genetic approaches so that, in the future, when we talk about genetic mutation that leads to a vulnerability for disease such as depression, or bipolar, or schizophrenia, we’d be able to actually say something about what that vulnerability really means. We might be able to say that the vulnerability involves abnormal activity in certain particular brain circuits that we’ve identified in MRIs by imaging people that we’ve done this genotyping on. Once we’ve narrowed that down, between the gene alteration and the abnormal activity in circuits, that is going to put us on the right path to new discoveries.

Another just really amazing discovery in just the past year came out of Stanford where in the Karl Deisseroth Lab they developed a way of making the brain, at least of animals, completely transparent so you can actually see straight through it. If you combine that technology with genetic tools for labeling cells you can track the connections within neural circuits with unprecedented precision. People are just now gearing up to apply this new technology and human brain material from people who have died but have lived lives where they’ve suffered from schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s Disease, and so on and we will be able, with unprecedented ability, to track the abnormalities in this brain tissue from people who have died with disease.

Increasingly we’re adopting the tools of modern industrial production in neuroscience research. One of the things that made genetic research possible was the application of robots that carried out the hundreds and thousands and millions of repetitive tasks to do the sequencing. Well, the same robotic technology is being applied to neuroscience studies where it’s now possible to use robots to record the activity of different interacting neurons. Soon we’ll have this ability to record and sample neural material from these disease models of human disease and relate the changes in neurons to the underlying genetic vulnerability that we see in mental disease. This is a program that is being spearheaded here by Ed Boyden in the McGovern Institute.

Of course, there is a great need for us to develop really quantitative theories of brain function. The incredible, valuable role of theories is obvious in fields like physics and chemistry, for example, but in neuroscience that’s been really difficult to achieve because we’ve lacked a lot of the basic facts about how these neural circuits work. Again, just in the last several years, in part due to the new technology and rapid pace of discovery, we’re developing better and better theories about how neural circuits work. We have a new center at MIT – the Center for Mind, Brains, and Machines headed by Tommy Poggio, a faculty member at the Institute – that is funded by the National Science Foundation with the goal of understanding human intelligence, developing quantitative, testable theories of intelligent behavior, and then testing these ideas through these models and even through applications to intelligent machines. So, for example, there was an effort to develop intelligent robots that would have some aspect of human intelligence and be able to learn from new situations and make better decisions and so on. This is really, I think, part of the overall effort that we’ll be seeing in the next few years to put intelligence into many of the devices we operate with everyday and I think our evaluation of that kind of intelligence will be is it the kind of intelligence that a human being would have in the same situation? And this is the kind of thing that neuroscience will be contributing a lot to is this understanding of what that intelligent behavior really is.

So, I’ve emphasized the disease applications of neuroscience because, of course that’s our primary goal in neuroscience research, but again, going back to the basic research enterprise, understanding the human brain is surely the greatest frontier in science today. It will give us insight into the nature of ourselves and it will clearly require the effort of people all over the world. We, here at the McGovern Institute, have interactions with scientists all over the world, we’re helping to build neuroscience programs in other countries, we have a very active program in China, for example. We want to bring in worldwide neuroscientists to work on these programs and in return I think we will also gain a better understanding of how the human brain functions in different cultures – how there may be miscommunications between people across cultures because of basically how our brains are constructed and how we might do a better job of understanding and communicating with people with many varied backgrounds, different expectations, and so on. I know that was certainly one of the initial goals of Pat and Lore McGovern when they founded the Institute, was to lead to this increased communications between people which would certainly lead to a better and more peaceful world for us all.

Finally, the last thing I’ll mention is, of course, many of you may have questions about the ethics of neuroscience research: what does this all mean? What are the implications of neuroscience research for many of the ethical issues we are concerned about – privacy and so on? And I think that that’s another topic that needs to be included in the mix of issues in the upcoming years of neuroscience research – we need to be attentive to these issues, we need to engage people in all areas from around the world in all walks of life in this discussion, and in the end have, I hope, everyone understand that we’re all in this effort together, we’re all making the effort and we’ll all reap the benefits I hope of neuroscience research in the future.

So, I hope that has given you a bit of an introduction to what we’re trying to do here and the research we do and I’d be happy to answer some of your questions.

Mr. Tuan: Great, thank you so much for your very interesting introduction and talk. Thank you to our audience for enthusiastically sending questions and watching our talks. So today we chose questions that were sent from our audience to ask the professor today. The first question is: is it true that we only use 10% of the productivity of our brains? As a neuroscientist, can you tell me the ways to unlock the brain to its highest potential productivity?

Robert Desimone: I think that the figure 10% is a bit of an exaggeration. But the point, I think, is highly relevant, which is that we don’t, in fact, use our brain to its fullest potential in many cases. And one of the goals of neuroscience research is to expand opportunities for people to realize that potential and particularly to influence the education of our children. We’ve learn a tremendous [amount] about how the brain learns and the conditions in which the brain learns optimally. And we’re already doing studies here at the McGovern Institute to see how we can improve education in schools, applying principles of neuroscience. We have tests going on both here in Boston and in sites around the world. And I would see that as a huge goal – is to enhance the learning of people from children going to adults.

Interviewer: So the next question is: Is there anything I can do to keep my brain in old age?

Robert Desimone: Well, that’s a question a lot of people are struggling with today. There’s a lot of interest in that as we all get older. We’re all thinking about what we can do to keep our brains healthy in aging. And there are certainly some studies that suggest that challenging mental activity can keep the brain healthy. And I think there is also good evidence that keeping your body healthy has the indirect effect of keeping your brain healthy. I mean your brain is another organ in the body and so people who keep themselves fit and exercise, and so on, are likely to have better blood flow to the brain and that’s all going to help as we get older.

Interviewer: So our audience wants to ask can we predict our actions and emotional state by learning about our brains?

Robert Desimone: Prediction is a tricky issue. I would say we would understand better our actions and emotional reactions to things from understanding the brain. To just give you one example, some neuroscientists have done studies of empathy – how it is that we can feel sorry for people. And we’ve had subjects in brain imaging scanners observing videos of other people interacting and so on. And what has been found is that when you see someone being hurt, that you’re utilizing some of the same neuro-circuits you use when you yourself are hurt. So empathy seems to involve a brain system that relates back to yourself. How would I feel in that situation? And that is something that would be strongly encouraged, for people to take on that attitude. And the brain is sort of biased to that kind of approach.

Interviewer: So the next questions are about the prize the achievements of the Institute. First question: from 2014, the winners and the achievements of the McGovern Institute for Brain research will be honored by the Boston Global Forum, and later the achievements will be put in Boston Global Museum. Can you explain more about the Scolnick Prize of Neuroscience and its link to unlock the human brain?

Robert Desimone: I should say first of all that the Scholnick Prize was endowed by the Merck Pharmaceutical Company to honor Ed Scholnick, who was their director of research for many years – I think 25 years. Led to many of the major, new drug treatments that came out of work over those years. And Ed is right here in Boston. He’s over at the Broad Institute right across the street from our Institute, where he leads a group doing research on psychiatric disorders. He’s a giant in the field of medicine and biology. The prize is meant to honor neuroscientists who have done outstanding work either at the basic level or more translational – closer to disease. Every year, it’s different. This particular year, the prize is going to Huda Zaghbi, who I think really epitomizes the goal of neuroscience. She’s someone who has done both basic research on brain circuits and the role of genes, but has also done fantastic work on understanding a particular genetic form of autism. She’s developed animal models. She’s identified some of the gene variants in people, and someone who is clearly making a difference in clinical science, and based on this foundation of great work in neuroscience.

Interviewer: Our audience wants to ask, what is the greatest achievement of the McGovern Institute?

Robert Desimone: Well in the time that the McGovern Institute has been in existence since 2000, I would say certainly our greatest recognition was the Nobel Prize that was won by Bob Horvitz for his work on the genetic basis of program cell death – incredibly important discovery in really all of biology. [It] certainly affects our understanding of brain function. That will be hard to top. But we’ve had many of our scientists who have made fantastic discoveries. One of our most senior, distinguished scientists, Ann Graybiel, is very well known for her work on the neural-circuits involved both in Parkinson’s Disease and, as it turns out, same circuits playing an important role on how we learn habits, repetitive actions and so on. We have the development of optic genetics, which initially started at Stanford, but a lot of that work is going on in the McGovern Institute here today. We have some fantastic new work from our faculty member Feng Zhang editing the genome like editing our DNA like you would in say a word processor. Incredibly important new tools. So I would say those are some things I would highlight.

Interviewer: So what research does The Institute focus on?

Robert Desimone: You know, I think one of our biggest strengths, is that we haven’t chosen one narrow topic as an institute but we’re supporting work on, really, a lot of areas, which share fundamental neural-mechanisms. It turns out, [as] I just mentioned, neural-circuits involved in learning new habits turned out to be neural-circuits that are playing a role in Parkinson’s Disease. So certain neurotransmitters, dopamine, for example involved in Parkinson’s Disease, play a very important role in normal learning and so on, and so on. So we’re building on this base of overlapping circuits and functions and then making progress from there.

Interviewer: So the next question is about the future of brain research. What achievements do you want to obtain in the next five years?

Robert Desimone: Well, as a director of an institute, I guess there’s always a temptation to promise perhaps more than can be delivered and I never like to overhype the progress of research in a short time frame. I do think it is realistic to expect that in the next five years we will really have made substantial progress in mapping out this pathway from a genetic alteration to an altered neural-circuit that underlies an important psychiatric disease. This will happen from animal models all the way up to human subjects.

Interviewer: Can you give a prediction to when scientists can really unlock the brain?

Robert Desimone: Well, I expect that that will be part of the one aspect of what our species is involved with forever – we will always try to understand our brain more and more just like saying when will we really unlock the secrets of the universe. I think there’s practically an infinity of secrets to unlock. So I really think it’s going to be exciting as the discoveries continue to roll in over time.

Interviewer: Do you think it is possible to reproduce human brains once we have unlocked them? And do you think it will make people immortal?

Robert Desimone: To understand human brains and…

Interviewer: After we unlock them, can we reproduce human brains?

Robert Desimone: You mean like in software?

Interviewer: Yeah.

Robert Desimone: Actually, I have two friends that were having a debate years ago of how we might most likely achieve immortality: one would be through biological approaches where we would learn to stop the aging process and the other would be through software, where we would understand so much about brain function load, essentially, our brain operations into a computer and then when our bodies died out, we could live forever in computer software. Anyhow, my two friends debated the opposite sides; they took opposite sides on that bet and we’re still waiting to see how that bet turns out. I don’t know about transferring our full consciousness, but as I said earlier we’re certainly going to have many aspects of human intelligence emulated in software and computers and so on. All the devices that we interact with – our phones, our tablets and so on are all going to be increasingly intelligent and less frustrating for us to deal with.

Interviewer: Do you think the spirit contained in human brains will end once humans pass away?

Robert Desimone: Well this question of whether there is an immortal soul that would live on past the death of the brain itself, I think obviously it’s a religious issue that I don’t think scientists have a lot to contribute to. I think that there’s a very healthy dialogue between religious leaders and scientists now and both sides trying to learn from each other. But scientists are no different from anyone else in wondering about questions just like that.

Interviewer: Can you explain more about the sixth sense? Where is it located in our brains and how does it work?

Robert Desimone: By the sixth sense, I’m assuming you mean some paranormal ability – that people have some sense of what’s going on in the world or other people and so on or what’s going to happen in the future. And I must say that that is a question that scientists can do research on, whether people truly have these abilities. Frankly, the evidence for this has been unconvincing so far, that people can predict the future or have awareness of things that can’t be experienced through any of their other senses. So I think people are open-minded, would be convinced if there were convincing evidence that came forward but I don’t think currently there’s evidence for those kind of abilities.

Interviewer: Some computer science students and some mathematicians in Vietnam want to ask whether they have any chance to research at your McGovern Institute. And if they do, how can they apply for that?

Robert Desimone: As I mentioned earlier, we have a strong interest in supporting and helping to develop neuroscience around the world. If you came to visit the McGovern Institute, you will see that we have people here from countries all around the world and including from Vietnam and we welcome people who want to be trained here and so on. Our contact information is on the website. If there’s someone who wants to do research and so on, we’d be happy to talk with them. Of course we are always looking for sources of support for people to come here. We’ve had some donors who have come forward and offered their support for people from some countries but we’d like to build that base of support for students from around the world. And I look forward to that.

Interviewer: The next question is from a computer expert in Vietnam and he would like to ask, “I would like to work as an associate for the McGovern Institute. I have a scholarship in research, can the McGovern Institute sponsor a Visa J1 for me?”

Robert Desimone: We sponsor many visa’s for international students and scientists from around the world. So again, I can’t comment on a particular case from someone I don’t know but I would welcome this person to contact us and we can have that dialogue. I’m hoping to visit Vietnam in the not-distant future. I hope to meet some people there. You know, one of the things I found is that there is often some reluctance to take people from a country if you don’t know anyone there – just human nature. It’s hard to evaluate people when you don’t know anything about them about the people who are recommending them. I think we need to build up this communication among the faculty members at different universities in different countries so we all know each other and we can appreciate their evaluations when they tell us they have a great student that would like to work with us. I take that as a very, very high priority.

Interviewer: So this is our last question today. Buddism has principal brain and its spirit. Do you agree with that principle?