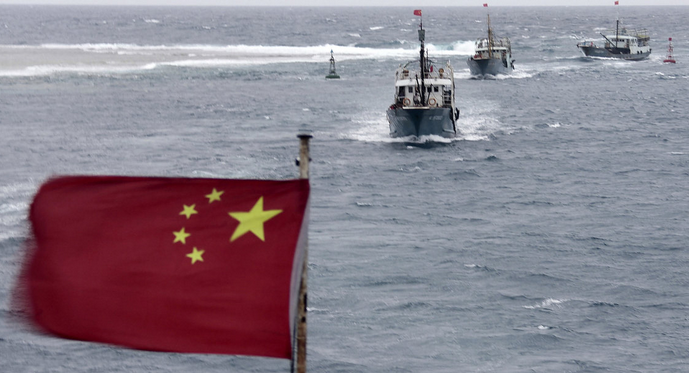

(Photo Credit: AP)

(BGF) – In this article featured in The New York Times, by Hugh White, addresses three policy options facing the U.S. regarding China’s aggression in East Asia. The first option would be for the U.S. to follow through on its agreement to defend Japan in the event that the tensions between China and Japan escalate into conflict. This option could embroil the U.S. in a war which it would have little control over. The second option would be for the U.S. to back out of its commitment to defend Japan, thereby leaving Japan to fend for itself. While this would avoid U.S. involvement in the war, it would greatly diminish the U.S.’s influence in Asia. The third option, which White endorses, is for the U.S. and China to reach an agreement in which the U.S grants China greater control in East Asia in exchange for China’s commitment to pursue its goals without aggression or the threat of force. Ultimately, this would require the U.S. and China to learn to share power, and more importantly, for China to learn to negotiate with its East Asian neighbors. An excerpt from the article is included below. Click here to read the full article.

Sharing Power With China

By Hugh White

CANBERRA, Australia — For 40 years American leadership has kept Asia stable and fostered economic growth, especially in China. But today China’s growing power is undermining that old order and posing big questions about America’s future role in the region.

Those questions loom in the ongoing dispute between China and Japan over a chain of tiny uninhabited islands in the East China Sea that could easily spark an armed clash between the two rivals. Such a conflict would escalate fast, and the United States would have to quickly take action to support Japan militarily against China — or not.

Washington remains neutral on who owns the islands, while criticizing China for using displays of force to challenge Japan’s de facto control of them. As Secretary of State John Kerry has said: “The United States, as everybody knows, does not take a position on the ultimate sovereignty of the islands. But we do recognize that they are under the administration of Japan.”

American officials have also affirmed support for Japan as an ally under the United States-Japan defense treaty. But it’s clear that Beijing doesn’t buy that. Instead, China has concluded America would stand back in an armed conflict, which is why it increasingly courts confrontation with Japan so brazenly. China’s ships and aircraft regularly patrol in areas claimed by Japan. Beijing’s declaration late last year of an air defense zone covering the islands took the confrontation to a new level.

Only a formal and explicit statement from President Obama laying out a new American policy will reduce the risk of a crisis in the East China Sea. What should Mr. Obama say?

If America makes it clear it would not support Japan in a fight with China, Tokyo’s confidence in the alliance will be shattered. Japan would then face its own choice: Rearm to defend itself against China without American help or submit to Chinese pre-eminence in Asia. Other American allies would also reconsider their options. American leadership in Asia would never be the same again. This is what China hopes will happen.

But a statement of unconditional support for Japan would commit America to a potential war that it could not control and probably would not win. We cannot assume China would simply back down: It has too much at stake. China does not want a war with America, but Beijing probably believes it could force a favorable draw. Ultimately, China is just as willing to fight to change the Asian order as America is to preserve it, and perhaps more willing.

Of course there are doves as well as hawks in Beijing, but even the doves believe China should be reclaiming its place as a great power in Asia. Beijing no longer thinks that American primacy is essential for the stability that China itself needs. No one in China, not even the more liberal-minded officials, believes that it’s their destiny to submit to American leadership indefinitely.

When both of America’s options are so bad, it is not surprising that the Obama administration finds it hard to articulate a clear policy. That is why Washington’s signals have been mixed, with the president remaining silent.

The fact is that, for America, these East China Sea islands, called Senkaku in Japanese and Diaoyu in Chinese, are not worth a fight with China. Still, preserving the American alliance with Japan, its regional leadership role and the whole Asian status quo are vital United States interests.

There is a third way. An American policy not to fight for the status quo does not have to lead inevitably to Chinese hegemony in Asia. A new Asian security arrangement could be forged in which America concedes a larger share of leadership to China but remains engaged to balance and limit Chinese power and help uphold key norms — including the all-important norm against the use or threat of force to settle disputes.

Ultimately this norm is more important than any particular alliance. It is the foundation of America’s post-1945 vision of international order. Washington should worry more about China’s willingness to defy this norm in the East China Sea than about its determination to challenge the United States-Japan alliance and change the regional order. America should be willing to fight China to protect that norm. This makes Washington’s choice a little clearer.

Mr. Obama should say that he is willing to negotiate a new security arrangement in Asia that accords China a bigger share of regional leadership, but only if China forgoes the use or threat of force to compel such changes.

If China persists in threatening the use of force, then America should be willing to fight, and must say so clearly. If China is prepared to desist, then America should be willing to talk about sharing power, and it should say that clearly, too.

We cannot know exactly how this kind of regional power-sharing would work. It would have to be negotiated with China and with the region’s other great powers. The best historical template might be the Concert of Europe that kept the peace in Europe for the 100 years until 1914 — based on principles of equality and power-sharing among the big players.

Like Europe then, Asia today needs a new arrangement in which no country has a unique leading role, and all the great powers agree not to seek primacy over the others. All the big regional questions would then have to be settled by negotiation between equals.

It would mean a lot of give and take. For example, America might accept that China will eventually assert control over Taiwan, and in return China could accept that it cannot make a territorial claim over the whole South China Sea.

Click here to continue reading.