With all eyes on Bangladesh, it’s worthwhile to take a look at safety standards in garment factories in other countries. An International Labor Organization report discloses a disappointing decline in worker safety in Cambodia.

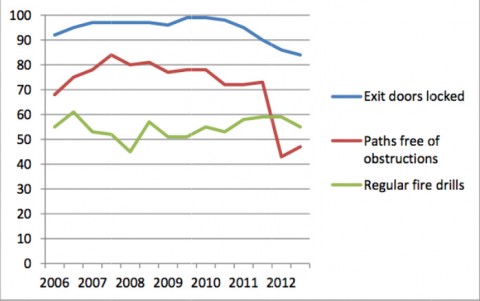

Fire safety standards in Cambodian garment factories are worse than what they were seven years ago

For international retailers who have committed more than $250 million to improve factory workers’ safety in Bangladesh, the conditions in Cambodia should give them pause.

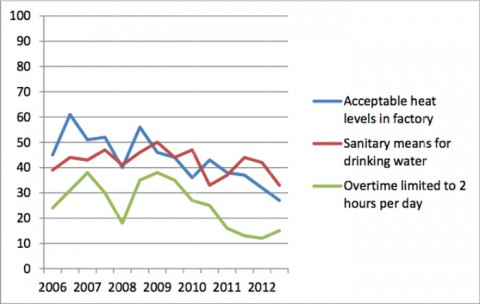

A bi-annual report (pdf) from the International Labor Organization-sponsored Better Factories program reveals a disturbing decline in working conditions in Cambodia’s garment factories. In the November 2012-April 2013 period, Better Factories found that the compliance to fire safety and worker health regulations were lower than what they were seven years ago.

Of the 155 factories assessed, 53% had obstructed access paths, compared with a little more than 30% in 2006, nearly 45% failed to conduct regular fire drills, and 15% kept emergency exit doors locked during working hours.

The report also highlights serious violations including excessive heat levels, shortage of safety masks, lack of proper equipment for handling chemicals and inadequate access to clean drinking water.

Cambodia is among the Southeast Asian countries that have benefitted from the double-digit wage increases and shortage of factory labor in China (paywall). The number of apparel export factories in Cambodia has surged from 185 in 2001 to 412 in April 2013 (pdf). Last year, the garment industry generated over $4.6 billon in exports, accounting for 84% of Cambodia’s total exports. The garment factories employ around 2.5% of Cambodia’s 15 million citizens and remittance payments from factory workers to families in rural regions sustain about 20% of the population, according to Japan External Trade Organization (pdf).

But the industry has been marred by mishaps and labor unrest in recent months. In May, accidents at two factories, including one that left two people dead when part of a shoemaking factory collapsed, highlighted unsafe conditions. Local media pounced on instances of workers fainting because of poor air circulation, and factory owners threatening to fire employees who refused to work overtime. Workers complained that the prevalence of short-term contracts lasting three to six months made it easier for employers to fire workers who joined unions (paywall) or demanded benefits like maternity leave.

A series of strikes over pay and conditions forced the factory owners to agree to a20% wage hike effective from May. Thanks to pressure by the Cambodian government, employers raised the monthly minimum wage from $61 to $75 and boosted employee healthcare stipends by $5 per month. Unions argue that, adjusted for inflation, those wages are on par with pay levels in the year 2000.