by Admin | Oct 14, 2013 | Highlights

Boston Global Forum (BGF) had another opportunity to speak with Arnold Zack, an Arbitrator and Mediator of over 5,000 Labor Management Disputes since 1957; former President of the Asian Development Bank Administrative Tribunal; designer of employment dispute resolution systems;; occasional consultant for the governments of the United States (Department of State, Peace Corps, Department of Labor, Department of Commerce), Australia, Cambodia, Greece, Israel, Italy, Philippines, and South Africa, as well as the International Labor Organization, International Monetary Fund, Inter-American Development Bank, and UN Development Program. He has also been a Member of Four Presidential Emergency Boards (chair of two). (Harvard Law School), and currently teaches at the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School.

BGF: Following up on our previous conversation, I had an opportunity to sit down with Professor Kent Jones of Babson College, who described the situation in which Cambodia came to be an ideal location for the International Labor Organization, and their offspring, The Better Factories Cambodia, to come in and establish reasonably acceptable working standards. However, Professor Jones also warned that further replication of the model is not possible elsewhere. What is your opinion on this matter and what else do you think a group like Boston Global Forum can do to address this issue?

Arnold Zack: The Cambodian situation arose during a unique period of history and can probably not be replicated at the moment. However, there was a piece in the Wall Street Journal on Sept 23rd, 2013 reporting that Better Factories Cambodia is about to begin publicizing compliance of firms with 21 standards, including worker rights, fire safety and treatment of unions. Several international brands and firms (including Wal-Mart) have endorsed the program while the Cambodian government and the Garment Manufacturers Association have opposed it. Such a program would not be possible without independence from Cambodian control, and freedom from the corruption that plagues national government intervention in most efforts and improving worker conditions in Southeast Asia

As to what the Forum could do, I would love to see a replication in some other countries in South East Asia, ie. Bangladesh, Myanmar or Vietnam. Such replication would have to come from more powerful organizations, although the focus on Bangladesh at the present might make that a possibility. I am not sure if the ILO is looking to be involved, even though they have set up similar programs in Africa.

Right now, I think the real need is getting existing Codes of Conduct implemented in these countries, and not focusing on establishing new ones. The Codes themselves are meaningless and multitudinous. Local factories ignore them. Ideally, local governments would help enforce them as in the case of Brazil, where graft is not such a problem. That is why international initiatives such as by the ILO are keys to advancement. I do not think the WTO is a player or wants to be. They are serious about enforcing intellectual property covenants and codes, but have clearly restrained themselves from involving in any social clauses or workplace codes.

Finally, I don’t think there is any route through the World Bank or the IMF. Having been involved with both organizations over the years (I led a survey team on reforming the Funds internal dispute resolution system), I can attest to their disinterest in social responsibility issues. Individual staff members might be interested but their focus is necessarily on dealing with financial and fiscal problems of governments and in gigantic infrastructure projects with no jurisdiction over workplace conditions.

Related article:

by Admin | Sep 13, 2013 | Highlights

[For Part 2, please click here]

Boston Global Forum (BGF) had an opportunity to sit down with Professor Kent Jones of Babson College. Dr. Jones specializes in trade policy and institutional issues, particularly those focusing on the World Trade Organization. He has served as a consultant to the National Science Foundation and the International Labor Office and as a research associate at the U.S. International Trade Commission, and was senior economist for trade policy at the U.S. Department of State. Dr. Jones is the author of numerous articles and four books, including Politics vs. Economics in World Steel Trade, Export Restraint and the New Protectionism, Who’s Afraid of the WTO? and most recently, The Doha Blues: Institutional Crisis and Reform in the WTO.

BGF: As an authority on international trade, what do you think will be a possible solution to prevent another Bangladeshi tragedy from happening?

Professor Kent Jones: As any economists would point out, the problem is clear—the building’s standard was extremely poor and, thus, a possible solution must involve the improvement of building standards in factories around the world. However, this is a very complicated task to achieve, and any meaningful procedure must include leadership from multiples fronts—the multinationals, the government, humanitarian groups, NGOs, groups like Boston Global Forum and international organizations such as the ILO [International Labor Organization]. The ILO does have an international labor standard and the ability to send in teams to investigate the safety of factories. However, the problem arises when the ILO does not have enforcement authority, meaning that, even though it can raise concerns over any violations of working standards, the ILO does not have any rights to punish or sanction the respective country. The case for the WTO, however, can be more interesting. As for the idea of having the WTO address this problem, this seems to be attractive to many people, since the WTO does have the authoritative power of pressuring member countries [Bangladesh has been a member since 1995]. The procedure is as follows: if a member nation violates a WTO trade agreement, that country would have to send a representative to present in front of the WTO Dispute Settlement court in Geneva. If the country is found guilty of violating any trade codes, the WTO would allow a certain period of time for the country authority to change its policy. Eventually, if nothing happens, the WTO may then allow the country’s trading partners to raise tariff and/or other fines. Thus, it is an attractive idea that the WTO should play a role in preventing a Bangladeshi tragedy to happen again. Unfortunately, this idea will not work. First, the WTO has a very small budget [195 million Swiss Franc in 2013]. More importantly, the WTO does not protect international labor standard at the moment, and I am skeptical that any discussions to include this issue into the current code would be effective, because every time the WTO adds a certain policy, it has to receive approval from all of its 159 members.

In any cases, our best hope is to have the multinationals at the forefront of this issue, for a number of reasons, but the most important is that these brands all have images they need to keep in the eyes of the consumers. If, for example, Walmart, Macy’s and JCPenney sit down together and develop a “code standard” that requires their subcontractors to maintain the international labor standard, there is possible progress we can rely on.

BGF: You already discussed about the WTO’s role in solving this issue, how about the World Bank and the IMF?

Professor Kent Jones: These two organizations indeed have much larger budgets than the WTO and do have powers to achieve what we hope. The IMF, however, does involve in larger scale projects, for example, improving a country’s financial services sector. The WB, on the other hand, has a lot of potential to be an impactful force on the quest to improve labor standards in the countries which it provides financing.

BGF: Thank you for your time, Professor.

by Admin | Sep 5, 2013 | Highlights

A distinguished leader and highly respected advocate for human rights, Michael Posner, has contributed extensively to the cause throughout his career. Former Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor at the State Department, Posner helped establish the Fair Labor Association (FLA), an organization that strives to improve working conditions in the apparel industry through collaborative efforts and dialogue with corporations, universities and NGOs. In 2013, Michael Posner joined New York University’s Stern School of Business, as Professor of Business and Society, to launch the first-ever Center for Business and Human Rights. This center will serve as resource tool for students to teach them the value of human rights in business, and will also work as a facility for public education and advocacy.

In this interview with Boston Global Forum (BGF), Michael Posner talks about the genesis and growth of the FLA, the need for collaborative effort from companies and governments to impact human rights issues, the urgency to educate consumers about their products and the definition of ‘sustainability’ in business.

Michael Posner. Credit- NYU/Stern

BGF: What were some of the challenges you faced when setting up the Fair Labor Association (FLA) in the 1990s? Did you get a lot of support from companies or did you have to work hard to motivate them?

Michael: That’s a big question. The FLA grew out of a White House initiative called the Apparel Industry Partnership, which was precipitated by crises in both Central America, with Kathie Lee Gifford producing goods for Wal-Mart in Honduras, and in the United States, where a Labor Department investigation revealed a group of Thai women being held against their will in factories in east Los Angeles. In response, President Clinton and Secretary of Labor Robert Reich created the Apparel Industry Partnership (AIP) that brought companies, unions and NGOs to the table. I don’t think very many people had high hopes for the AIP but at the same time, they didn’t want to not be there. The expectation for many was that the first meeting in August of 1996 also would be the last meeting. In fact, when Robert Reich convened a second meeting a month later he said, “the fact that we’re all meeting the second time means that this has exceeded our wildest expectations.”

Over time, trust grew among the group and participants stayed at the table. We spent a year-and-a-half defining standards for working conditions in the apparel industry and developing a methodology for implementing an agreement on standards. During this period, Guess Jeans and Kathie Lee (representing Wal-Mart) dropped out of the group. The unions, too, dropped out after an intense internal fight. At the end of the day, the American Federation of Labor and Unite Union made a judgment that they couldn’t support an agreement that made it easier for companies to go to China and places where union activity was restricted. Even without these companies and unions, there was enough trust and confidence in what we had developed that we were able to launch the Fair Labor Association in 1999.

BGF: Why do you think companies dropped out? Is it just about profits and about the money that it takes to enforce worker safety standards or does it stem from larger issues like a fear of responsibility or obligation?

Michael: It’s more complicated than that. On the one hand, there are issues of brand reputation. It’s easier for a highly brand-sensitive company like Nike or Adidas to devote resources to improving working conditions than it is for a company like Wal-Mart that competes on the basis of low prices. Many companies think about these issues in terms of reputational risk and mitigating the potential of ending up on the front page for producing products using sweatshop or child labor.

On the other hand, companies are also thinking about these issues in terms of business sustainability. Companies in the manufacturing sector need a reliable supply chain that can produce quality products on schedule and to their design specifications. Decent working conditions and factory safety undergird the sustainability of this system. The premise of the FLA is that no company can successfully address these issues acting alone. Companies facing common human rights challenges in the same industry will be more successful if they work collectively. In many ways, this is the hardest part because these companies are fierce competitors and they’re not comfortable disclosing their vulnerabilities to others in the same industry. Despite the discomfort, many companies have recognized that they need critical mass to make a difference and have found ways to work together.

BGF: Do you think that companies in the west have enough power to yield immediate influence in poor countries like Bangladesh, where political and social reform might take several years to come about, if at all?

Michael: These are a big, seemingly intractable problems. Bangladesh is an exceedingly poor country that took advantage of trade quotas in the 1970s by quickly building up infrastructure to produce high volumes of garments very cheaply. While Bangladesh is the world’s second largest producer of readymade garments, it remains a very weak state and there is little enforcement of safety or labor regulations in the garment sector.

In the long term, a stronger national government with the capacity and inclination to regulate its domestic industries is the obvious solution to protecting workers’ rights and enhancing workplace safety. But as you say, that kind of reform will take years and even decades. In the mean time, there is a governance gap. It’s tempting to say that big Western multinationals can fill that gap on their own. But the reality is that while the brands are a very important player, they cannot do it alone. In the short- to medium-term, enhancing working conditions in Bangladesh will require action by the brands, the government, the local manufacturers’ association, Bangladeshi and international civil society, Western governments, the ILO, and the international financial institutions.

The larger fundamental issue is how do you think about a sourcing model that allows global brands and local manufacturers to grow their profits while ensuring worker safety, well-being and dignity.

BGF: What advice do you have for Boston Global Forum, a non-profit based in the US? Shall we focus on consumer education or government policy or something completely different?

Michael: I think the answer is all of the above. You’ll have to decide where you have a unique capacity to make a difference. I know Governor Dukakis has thought about statutory regulation in the United States focused on business and human rights. I don’t know if that’s politically possible, but it’s certainly the way issues like corruption have been dealt with.

Another aspect that is very important is the consumer piece. Consumers have a difficult time differentiating among companies and understanding what their choices are when it comes to ethically produced products. There’s a lot of work to be done there.

Third, there needs to be a broader discussion of what ‘sustainability’ means. When many companies talk about sustainability, they’re really talking about environmental concerns. That’s a very narrow understanding of sustainability. In my mind, sustainability encompasses not only the environment, but human rights, labor rights, and development. There needs to be a broader frame and a group like Boston Global Forum can play a role in identifying those companies that are willing to think more broadly about business sustainability over the long-term.

by Admin | Aug 5, 2013 | News

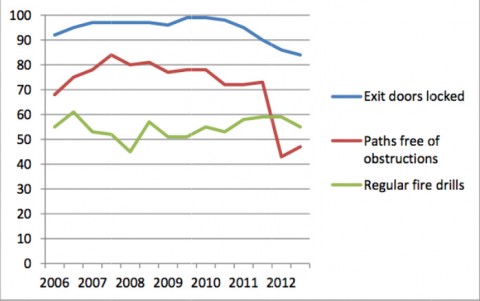

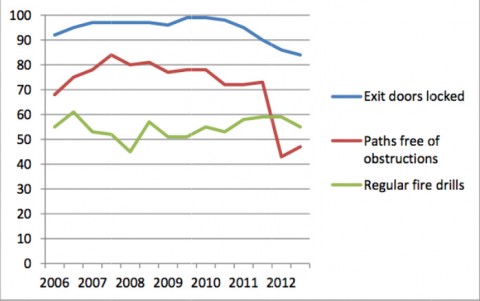

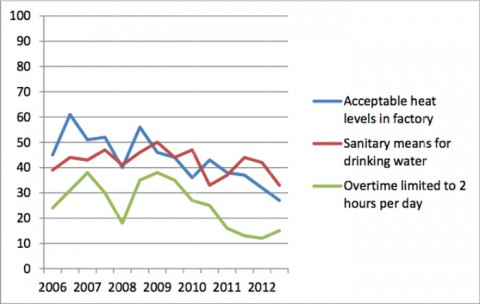

With all eyes on Bangladesh, it’s worthwhile to take a look at safety standards in garment factories in other countries. An International Labor Organization report discloses a disappointing decline in worker safety in Cambodia.

Credit- qz.com

For international retailers who have committed more than $250 million to improve factory workers’ safety in Bangladesh, the conditions in Cambodia should give them pause.

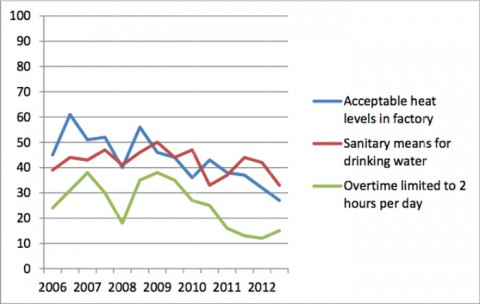

A bi-annual report (pdf) from the International Labor Organization-sponsored Better Factories program reveals a disturbing decline in working conditions in Cambodia’s garment factories. In the November 2012-April 2013 period, Better Factories found that the compliance to fire safety and worker health regulations were lower than what they were seven years ago.

Of the 155 factories assessed, 53% had obstructed access paths, compared with a little more than 30% in 2006, nearly 45% failed to conduct regular fire drills, and 15% kept emergency exit doors locked during working hours.

Credit-qz.com

The report also highlights serious violations including excessive heat levels, shortage of safety masks, lack of proper equipment for handling chemicals and inadequate access to clean drinking water.

Cambodia is among the Southeast Asian countries that have benefitted from the double-digit wage increases and shortage of factory labor in China (paywall). The number of apparel export factories in Cambodia has surged from 185 in 2001 to 412 in April 2013 (pdf). Last year, the garment industry generated over $4.6 billon in exports, accounting for 84% of Cambodia’s total exports. The garment factories employ around 2.5% of Cambodia’s 15 million citizens and remittance payments from factory workers to families in rural regions sustain about 20% of the population, according to Japan External Trade Organization (pdf).

But the industry has been marred by mishaps and labor unrest in recent months. In May, accidents at two factories, including one that left two people dead when part of a shoemaking factory collapsed, highlighted unsafe conditions. Local media pounced on instances of workers fainting because of poor air circulation, and factory owners threatening to fire employees who refused to work overtime. Workers complained that the prevalence of short-term contracts lasting three to six months made it easier for employers to fire workers who joined unions (paywall) or demanded benefits like maternity leave.

A series of strikes over pay and conditions forced the factory owners to agree to a20% wage hike effective from May. Thanks to pressure by the Cambodian government, employers raised the monthly minimum wage from $61 to $75 and boosted employee healthcare stipends by $5 per month. Unions argue that, adjusted for inflation, those wages are on par with pay levels in the year 2000.

by Admin | Jul 31, 2013 | Highlights

Credit- New York Times/ Taslima Akhtar

While developed countries debate regulations and trade impositions after the Rana Plaza collapse, Bangladesh needs to independently bolster reforms surrounding the garment industry. At present, the garment industry enjoys special privileges like subsidies and tax breaks and, they pay less tax as compared to other industries. Their factories, too, are not all build on legally obtained land, sometimes with environmentally detrimental consequences. The following New York Times article, reported by Jim Yardley, has the complete story.

Garment Trade Yields Power in Bangladesh

DHAKA, Bangladesh — In the honking, congested heart of this overcrowded capital, one glass office tower stands uniquely alone, surrounded by water, accessible by a small bridge. It is a symbol of the power of Bangladesh’s garment industry, the headquarters of the country’s most powerful association of factory owners. It is also illegal.

So said the Bangladesh High Court, concluding that the land had been illegally obtained, the building had been erected without proper approvals and the location threatened a network of lakes that form the natural drainage system of the capital. The High Court called the building “a scam of abysmal proportions” and ordered it demolished within 90 days.

That was two years ago. The building still stands. The case is now in a legal limbo — more proof, according to critics, of the power of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association. Members control the engine of the national economy — garment exports to the United States and Europe. Many serve in Parliament or own television stations and newspapers.

For two decades, as Bangladesh became a garment power, now trailing only China in global clothing exports, the trade group has often seemed more like a government ministry. Known as B.G.M.E.A., the organization helps regulate and administer exports and its leaders sit on high-level government committees on labor and security issues. Industry trade groups in the United States could only imagine such a role.

But the April collapse of the illegally constructed Rana Plaza factory building, which killed more than 1,100 people, has placed the entire global supply chain that delivers clothes from Bangladeshi factories to Western consumers under scrutiny. And the quasi-official garment group, in the eyes of its critics, presents a major conflict of interest at the center of Bangladesh’s troubles and is a big part of the systemic problems that have made the country a dangerous place for garment workers.

“You can’t put the fox in charge of the chickens,” said Rizwana Hasan, an environmental lawyer. “B.G.M.E.A. has no regulatory authority under the laws of the country. It’s a clubhouse of the garment industry.”

Bangladesh is working to restore the garment industry’s credibility after last month’s decision by the Obama administration to suspend a special trade preference for the country. The European Union is also considering penalties. Bangladesh has responded by passing new labor laws and pledging to inspect the structural safety and legal compliance of the nation’s 5,000 garment factories.

In both instances, the garment group’s interests were well represented. It has hired a team of engineers and is helping oversee the post-Rana Plaza factory inspections — even as the High Court cited the group for a litany of violations on its own headquarters. Meanwhile, the trade group brought its influence to bear in a lobbying campaign as Parliament amended the labor laws this month.

Bangladeshi officials promised to overhaul their labor laws, which fall short of standards defined by the International Labor Organization and tend to suppress unions, contributing to safety problems, labor advocates say. But the results of the overhaul were less significant, especially for the garment industry. One amendment required that industries create profit-sharing programs for workers. But exporting industries, notably the garment sector, were exempted.

Restrictions on labor organizing were eased, but far from fully lifted. The new law requires that 30 percent of factory workers must sign petitions to form a union, a telling obstacle given that many factories have thousands of employees and have few places to hold meetings and organize.

“Bangladesh had a golden opportunity,” said Roy Ramesh Chandra, a labor leader, who said that the political influence of factory owners diluted some of the amendments. “The employers have tremendous influence.”

Business interests dominate Bangladesh’s Parliament. Of its 300 members, an estimated 60 percent are involved in industry or business. Analysts say 31 members, or 10 percent of the country’s national legislators, directly own garment factories, while others have indirect financial interests in the industry.

Factory owners say their political clout is vastly overstated and dismiss suggestions that they exert influence over top elected leaders, and some analysts agree their influence is sometimes overstated. But the trade group clearly is part of the process in ways that set Bangladesh apart.

Three years ago, the prime minister created an industrial police force to maintain order in factory districts and act as an independent arbiter to solve disputes between workers and management. But many workers and labor organizers say the force almost always favors owners. The trade group is even supposed to buy patrol cars for officers.

“This organization is extremely powerful,” said one senior government official, who said much of its clout comes from political contributions. “The political parties are running after money.”

The trade group was formed in 1983 as Bangladesh, then one of the world’s poorest countries, was trying to build its economy by developing a garment industry. Initially, it had no headquarters and no bank account.

“When I first went out there, the B.G.M.E.A. was run out of a garage,” said Don Brasher, who worked as a trade consultant to Bangladesh for more than a decade. “It was not institutionalized at all.”

That quickly changed. Under the rules of global textiles, developing countries faced restrictions on garment exports and, in the case of the United States, were assigned trade quotas. Managing this quota system was critical and complicated. Bangladesh’s government decided to delegate administrative tasks to the trade group — including the authority to regulate certain transactions and collect fees.

“That was pretty extraordinary,” said Mr. Brasher, who lived in Dhaka for two years and worked closely with the group on the quota system. “Ordinarily, that is done by a government agency. There’s nothing like that, anywhere. But it was done out of necessity.”

Bangladesh’s government is notoriously corrupt and has limited bureaucratic capacity to handle the intricate mechanics of global trade. Politics is ferociously contested and marred by regular nationwide strikes, known as hartals. In this environment, the group became a stabilizing force as global trade rapidly grew.

Even after the quota system expired in 2005, the trade group steadily expanded its regulatory responsibilities. Today, it enjoys a near stranglehold on exports: only factories that are among its members are allowed to export woven garments, with some exceptions. The group regulates the importation of fabric and issues certificates of origin, the required proof that a garment is made in Bangladesh. It has arbitration committees to settle disputes and administers the often-complex practice of subcontracting.

On a recent evening, Atiqul Islam, the group’s president, sat at his desk and signed applications from factory owners seeking duty-free status to import machinery. A half-hour earlier, he had presided over a news conference about a skills training program for workers that the group had organized with the United Nations Development Program, the British international development agency UK-AID and the International Labor Organization.

“Zero power,” he said while signing the tax waiver applications, flicking away a question about the group’s influence. “The government decentralized a few things to us, so we are doing them. We can do it much faster.”

Many factory owners portray the industry as a public service, providing millions of jobs. The health of the garment sector is often seen as a national security issue, with the industry accounting for 80 percent of Bangladesh’s manufacturing exports and providing critical foreign exchange. It is the trade group that maintains order in daily operations of the industry, owners say.

“Otherwise, there would be chaos,” said Annisul Huq, a former president of the trade group. “Yes, we can criticize the B.G.M.E.A. But it has a very strong role. Somebody has to lead.”

Factory owners face many challenges in Bangladesh, including high interest rates on loans. But the heroic self-image of the sector is somewhat overstated. Garment factories enjoy subsidies and tax breaks not offered to other industries, and pay less tax. A recent study in a Bengali-language newspaper estimated that these subsidies and tax breaks exceeded tax revenues from the industry by roughly $17 million.

“The doors of the treasury are open for them,” said Badiul Alam Majumdar, secretary of the nonprofit group Citizens for Good Governance. “They extract all kinds of subsidies. They influence legislation. They influence the minimum wage. And because they are powerful, they can do, or undo, almost anything, with impunity.”

One unlikely critic of the trade group is Rubana Huq, the wife of Mr. Huq, who is now the managing director of the family’s garment conglomerate, Mohammadi Group. She said the garment industry in Bangladesh has matured and must be regulated by a transparent, independent arbiter, possibly a new government ministry.

“Of course, there is a conflict of interest,” she said. “There is no reason why a body like B.G.M.E.A. would be credible with the international players.”

Ms. Huq and other critics point to the headquarters building as a symbol of its protected status. Environmentalists have long protested and argued that the building’s location on a de facto island inside a city lake impedes the natural drainage network and contributes to flooding in the capital during the monsoon.

Illegalities abounded, according to the High Court ruling: construction started before the group had won final approval on a building plan; the land transfer from a government agency violated national laws on usage of public land. Yet the group’s leaders argue that the building’s status has been validated at the highest level: two prime ministers led different inauguration ceremonies at the site.

“It is not illegal,” said Mr. Huq, his voice rising. “We have applied to the government for the land. The government has given us the land. Two prime ministers have opened it. What validation do you want?”

But Iqbal Habib, an architect who designed the plan to renew the lake system, said the group could not be exempted from rules governing others. “They are always talking about their compliance with the buyers,” he said. “What about their compliance with the laws of the country?”

For now, the case is stalled. The Supreme Court is supposed to hold a final hearing, but with elections coming, the government has shown little interest in confronting the country’s most powerful industrial bloc. It is unclear if a hearing will take place.

“It has gone to the Supreme Court,” Mr. Huq said. “That could take forever. It is Bangladesh. We have full trust — as long as they give a verdict in our favor.”

He is smiling, joking, to a degree.

Julfikar Ali Manik contributed reporting.

by Admin | Jul 24, 2013 | Highlights

The following article has been written by Leonie Barrie, managing editor of just-style.com. To read the article on its source website, please click here.

Source-www.bangladeshnewsnow.com

US: Action Plan Sets Out Bangladesh GSP Safety Steps

The US government has set out a series of steps that Bangladesh needs to implement – including improved worker rights and worker safety in the country’s garment industry – if it wants trade preferences to be restored.

The “action plan” released on Friday (19 July) comes three weeks after the Obama administration decided to suspend Bangladesh’s tariff benefits under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) programme over concerns about safety issues.

Among its recommendations are hiring more government labour, fire and building inspectors, and improve their training. It also wants to see increased fines and other sanctions, including loss of import and export licenses, applied to ready-made garment and knitwear factories that fail to comply.

The administration is also calling for a publicly accessible database of all RMG/knitwear factories as a platform for reporting labour, fire, and building inspections, including information on the factories and locations, violations identified, fines and sanctions administered, factories closed or relocated, violations remediated, and the names of the lead inspectors.

And it wants to see an effective complaint mechanism, including a hotline, set up for workers to confidentially and anonymously report their concerns.

Bangladesh is also being urged to enact and implement labour law reforms to address key concerns related to freedom of association and collective bargaining. And it must protect unions and their members from discrimination and reprisal.

The decision to suspend US trade preferences was taken after a fire at the Tazreen Fashion factory killed 114 people in November last year, and the Rana Plaza building collapsed in April killing more than 1,100 garment workers.

The tariff preferences being cut largely cover imports of tobacco, sports equipment, porcelain and plastic products. They do not cover the country’s garment industry, which represents the lion’s share of trade with the US and are subject to import duties ranging between 15% and 32%.

According to Otexa figures, the US imported some US$4.63bn worth of apparel from Bangladesh in the year to May 2013, a rise of 3.1% on the year before and giving it a 5.9% share of the total apparel imported by the US over the period.

The US government has also emphasised the important role played by retailers and brands to ensure that the factories from which they source are compliant with all fire and safety standards in Bangladesh.

“We urge the retailers and brands to take steps needed to help advance changes in the Bangladeshi garment sector and to work together and with other stakeholders to ensure that their efforts are coordinated and sustained,” said a joint statement from the Department of State, the Department of Labor, and the Office of the United States Trade Representative.

North American brands and retailers earlier this month unveiled a new five-year plan to improve worker safetyat the factories in Bangladesh that produce their clothes.

The Bangladeshi government is also making changes to its labour laws in response to domestic and international pressure, although activists say the amendments still don’t do enough to protect worker’s rights or meet international standards

The US added that its action plan is “broadly consistent” with a new “global compact” – the Sustainability Compact for Continuous Improvements in Labour Rights and Factory Safety in the Ready-made Garment and Knitwear Industry in Bangladesh – set out on 8 July.

The US is also joining this group as a partner with the European Union (EU), Bangladesh, and the International Labor Organization (ILO).

Bangladesh Action Plan 2013

- Develop, in consultation with the International Labor Organization (ILO), and implement in line with already agreed targets, a plan to increase the number of government labor, fire and building inspectors, improve their training, establish clear procedures for independent and credible inspections, and expand the resources at their disposal to conduct effective inspections in the readymade garment (RMG), knitwear, and shrimp sectors, including within Export Processing Zones (EPZs).

- Increase fines and other sanctions, including loss of import and export licenses, applied for failure to comply with labour, fire, or building standards to levels sufficient to deter future violations.

- Develop, in consultation with the ILO, and implement in line with already agreed targets, a plan to assess the structural building and fire safety of all active RMG/knitwear factories and initiate remedial actions, close or relocate inadequate factories, where appropriate.

- Create a publicly accessible database/matrix of all RMG/knitwear factories as a platform for reporting labour, fire, and building inspections, including information on the factories and locations, violations identified, fines and sanctions administered, factories closed or relocated, violations remediated, and the names of the lead inspectors.

- Establish directly or in consultation with civil society an effective complaint mechanism, including a hotline, for workers to confidentially and anonymously report fire, building safety, and worker rights violations.

- Enact and implement, in consultation with the ILO, labour law reforms to address key concerns related to freedom of association and collective bargaining.

- Continue to expeditiously register unions that present applications that meet administrative requirements, and ensure protection of unions and their members from anti-union discrimination and reprisal.

- Publicly report information on the status and final outcomes of individual union registration applications, including the time taken to process the applications and the basis for denial if relevant, and information on collective bargaining agreements concluded.

- Register non-governmental labour organisations that meet administrative requirements, including the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity (BCWS) and Social Activities for the Environment (SAFE). Drop or expeditiously resolve pending criminal charges against labour activists to ensure workers and their supporters do not face harassment or intimidation. Advance a transparent investigation into the murder of Aminul Islam and report on the findings of this investigation.

- Publicly report on the database/matrix identified above on anti-union discrimination or other unfair labour practice complaints received and labour inspections completed, including information on factories and locations, status of investigations, violations identified, fines and sanctions levied, remediation of violations, and the names of the lead inspectors.

- Develop and implement mechanisms, including a training programme for industrial police officers who oversee the RMG sector on workers’ freedom of association and assembly, in coordination with the ILO, to prevent harassment, intimidation and violence against labor activists and unions.

- Repeal or commit to a timeline for expeditiously bringing the EPZ law into conformity with international standards so that workers within EPZ factories enjoy the same freedom of association and collective bargaining rights as other workers in the country. Create a government-working group and begin the repeal or overhaul of the EPZ law, in coordination with the ILO.

- Issue regulations that, until the EPZ law has been repealed or overhauled, will ensure the protection of EPZ workers’ freedom of association, including by prohibiting “blacklisting” and other forms of exclusion from the zones for labour activities.

- Issue regulations that, until the EPZ law is repealed or overhauled, will ensure transparency in the enforcement of the existing EPZ law and that require the same inspection standards and procedures as in the rest of the RMG sector.

The following article is reported from Bangladesh News Now. Click here to read the full article.

Bangladesh Hopes US to Revive GSP

Dhaka: Bangladesh hopes that the US administration will soon revive its GSP status and the buyers will continue their business with their long-trusted partners.

Affirming that it will remain engaged with all its trading partners to share ideas and collectively address factory safety issues, Bangladesh also hoped that the US-Bangladesh trade to grow further despite the suspension of GSP, a benefit a least developed country is supposed to receive in the developed countries as per the provisions of the World Trade Organization.

“The government of Bangladesh has come to know about the unfortunate development of GSP suspension in the USA. Indeed a section of people, inside both Bangladesh and the USA, had long been campaigning to this effect,” said a Foreign Ministry release on Friday.

It cannot be more shocking for the factory workers of Bangladesh that the decision to suspend GSP comes at a time when the government of Bangladesh has taken concrete and visible measures to improve factory safety and protect workers’ rights, the Foreign Ministry note said.

Amendments to the 2006 labour act, ILO-led government-employer-worker tripartite agreement to implement time-bound decisions, and formation of a ministerial committee to ensure compliance in garments factories should speak for the Bangladesh government’s seriousness in the matter.

It said Bangladesh is absolutely respectful of a trading partner’s choice of decisions, it expresses its deep concern that this harsh measure may bring in fresh obstacles to an otherwise flourishing bilateral trade.

“Bangladesh believes that its partnership with the USA is founded on certain core values such as democracy, human rights, the rule of law, women empowerment, freedom of expression and social justice.”

It said the resilient nature of the Bangladeshi people – as manifested in 1971 when they earned freedom in the face of ordeals at home and abroad – must help them improve the quality of life and earn respect as an enterprising nation.

Bangladesh enjoys an extensive partnership with the USA in multiple areas such as democratic institutions building, empowering grassroots people, protecting economically and socially vulnerable groups, countering terrorism, contribution to global peace, and most importantly, a lasting business-to-business connectivity, the release added.