by Admin | Oct 14, 2013 | Highlights

Boston Global Forum (BGF) had another opportunity to speak with Arnold Zack, an Arbitrator and Mediator of over 5,000 Labor Management Disputes since 1957; former President of the Asian Development Bank Administrative Tribunal; designer of employment dispute resolution systems;; occasional consultant for the governments of the United States (Department of State, Peace Corps, Department of Labor, Department of Commerce), Australia, Cambodia, Greece, Israel, Italy, Philippines, and South Africa, as well as the International Labor Organization, International Monetary Fund, Inter-American Development Bank, and UN Development Program. He has also been a Member of Four Presidential Emergency Boards (chair of two). (Harvard Law School), and currently teaches at the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School.

BGF: Following up on our previous conversation, I had an opportunity to sit down with Professor Kent Jones of Babson College, who described the situation in which Cambodia came to be an ideal location for the International Labor Organization, and their offspring, The Better Factories Cambodia, to come in and establish reasonably acceptable working standards. However, Professor Jones also warned that further replication of the model is not possible elsewhere. What is your opinion on this matter and what else do you think a group like Boston Global Forum can do to address this issue?

Arnold Zack: The Cambodian situation arose during a unique period of history and can probably not be replicated at the moment. However, there was a piece in the Wall Street Journal on Sept 23rd, 2013 reporting that Better Factories Cambodia is about to begin publicizing compliance of firms with 21 standards, including worker rights, fire safety and treatment of unions. Several international brands and firms (including Wal-Mart) have endorsed the program while the Cambodian government and the Garment Manufacturers Association have opposed it. Such a program would not be possible without independence from Cambodian control, and freedom from the corruption that plagues national government intervention in most efforts and improving worker conditions in Southeast Asia

As to what the Forum could do, I would love to see a replication in some other countries in South East Asia, ie. Bangladesh, Myanmar or Vietnam. Such replication would have to come from more powerful organizations, although the focus on Bangladesh at the present might make that a possibility. I am not sure if the ILO is looking to be involved, even though they have set up similar programs in Africa.

Right now, I think the real need is getting existing Codes of Conduct implemented in these countries, and not focusing on establishing new ones. The Codes themselves are meaningless and multitudinous. Local factories ignore them. Ideally, local governments would help enforce them as in the case of Brazil, where graft is not such a problem. That is why international initiatives such as by the ILO are keys to advancement. I do not think the WTO is a player or wants to be. They are serious about enforcing intellectual property covenants and codes, but have clearly restrained themselves from involving in any social clauses or workplace codes.

Finally, I don’t think there is any route through the World Bank or the IMF. Having been involved with both organizations over the years (I led a survey team on reforming the Funds internal dispute resolution system), I can attest to their disinterest in social responsibility issues. Individual staff members might be interested but their focus is necessarily on dealing with financial and fiscal problems of governments and in gigantic infrastructure projects with no jurisdiction over workplace conditions.

Related article:

by Admin | Sep 27, 2013 | Highlights

[For Part 1 of our discussion, please click here]

Dr. Jones specializes in trade policy and institutional issues, particularly those focusing on the World Trade Organization. He has served as a consultant to the National Science Foundation and the International Labor Office and as a research associate at the U.S. International Trade Commission, and was senior economist for trade policy at the U.S. Department of State. Dr. Jones is the author of numerous articles and four books, including Politics vs. Economics in World Steel Trade, Export Restraint and the New Protectionism, Who’s Afraid of the WTO? and most recently, The Doha Blues: Institutional Crisis and Reform in the WTO.

In light of some recent developments Boston Global Forum (BGF) has made, we had an opportunity to sit down with Professor Kent Jones of Babson College again to explore other possible solutions for our topic. Readers of our previous posts may have noticed that BGF was able to identify Better Factories Cambodia as a possible model for other countries to replicate. However, according to Professor Jones, there is a reason why this strategy may not be possible.

BGF: Many experts attributed the success of Better Factories and the International Labor Organization’s involvement in Cambodia to a trade agreement between the U.S and Cambodia in 1999, which basically required improved labor conditions for factory workers in exchange for a higher percentage of quota for garment exports into the U.S. If this is the case, why do you think that the U.S government, or any other Western powers, did not re-implement a similar agreement in order to incentivize local authorities to come up with better working conditions for garment workers in their countries?

Professor Kent Jones: There was indeed a formal special textiles/clothing trade agreement between Cambodia and the US in 1999, which led to improvements in working conditions there. Unfortunately, the circumstances that allowed this agreement have changed, and it is no longer possible to replicate it for other countries.

At the time, Cambodia, like all other developing countries, was subject to the Multifiber Agreement (MFA), a global system of trade quotas on nearly all categories of clothing sold in the US, Europe and other industrialized countries. Each exporting country typically had certain quota shares in the US market, which were strictly controlled.

The US-Cambodia agreement was designed to provide an incentive for Cambodia to improve worker rights and working conditions in exchange for significant increases in its quota access to the US market. As part of the arrangement US AFL-CIO representatives went to Cambodia to organize workers there and monitor progress. There were controversies during those years as to how much progress was being made, but in the end Cambodia did receive increased market access as a result of the reforms that took place.

There were two important elements of the deal that were crucial in making it work. One was that the MFA ruled the world textile/clothing market. This global system of quotas allowed countries like the US to offer special deals to certain countries based on criteria such as progress on worker rights (other deals were based on political criteria). The second element was that Cambodia was not in the WTO; it joined eventually in 2004.

These circumstances were important because the MFA was being phased out at the time for members of the WTO, based on the new agreements of the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations, completed in 1994. As long as the MFA was in force, Cambodia could benefit from its special agreement on market access with the US, since all other countries were restricted by MFA quotas. As the MFA was phased out over the period 1995-2005, all WTO countries were gradually allowed more and more unfettered access to the US and European markets, which was eroding the benefits of any extra quota access granted to Cambodia.

Still, the US-Cambodia deal allowed the US to continue the incentive program until Cambodia joined the WTO (after a long accession process) in 2004. At that point, Cambodia was entitled to the full benefits of the MFA phase-out that was completed in 2005. The US no longer had any leverage to control Cambodian market access to the US, based on the MFN treatment Cambodia received upon joining the WTO, and the MFA phase-out that now applied to Cambodia as well.

We now have a quota-free global trading environment in textiles and clothing. Tariffs are still imposed on these products, but they are regulated by the WTO tariff binding rule, which prohibits countries from raising tariffs unilaterally. In addition, the MFN rule prohibits WTO members from raising tariffs against any other individual WTO member on a discriminatory basis. Thus a deal like the earlier US-Cambodia agreement would no longer be possible for any WTO members, including Bangladesh.

The legacy of the agreement was that it gave the ILO, workers’ rights and labor unions a foothold in Cambodia, and these groups continue to have some impact there. Improvements in working conditions and worker rights in Bangladesh and other countries will have to come from other strategies besides intergovernmental trade deals.

This is why, as I suggested in our discussion a few weeks ago, that company codes of conduct, backed up with consumer group or NGO pressure, would be the most promising path.

Otherwise, a formal plan for improving a country’s work environment would require the government itself to agree to ILO and/or outside group monitoring of labor conditions. The US and other countries may need to find other means of leverage in order to persuade reluctant governments to implement reforms.

BGF: Thank you for your insights, Professor.

by Admin | Sep 27, 2013 | Highlights

Even though championed by many people as the representative model for the improvement of international labor standard, Better Factories Cambodia has recently come under pressure and criticism from both the Cambodian government and the factory association when the group decided to introduce an extensive initiative to improve garment workers’ conditions. This dilemma comes as the authority argues that tougher supervision will force businesses out of Cambodia and into less-regulated neighboring countries. This is clearly an existing paradox that any country must solve. If you were the Prime Minister or President of Cambodia? What should you do?

Boston Global Forum will work on these propositions in the coming month and will convene for another round of discussions in October 2013. If you wish to join our conversation or participate in our meetings, please send in your request to our Editor-in-Chief, Mr Nguyen Anh Tuan at [email protected]

The original story was reported by Kate O’Keeffe of the Wall Street Journal.

U.N.-Backed Group to Publicize Safety Failings Over Government Objection

A monitoring group backed by the United Nations said it would begin to publicize garment factories’ compliance with worker rights and safety standards in Cambodia, a controversial program that its organizers say will be the world’s most extensive initiative to improve working conditions at plants.

Photo: European Pressphoto Agency

Photo: European Pressphoto Agency

A group plans to publicize compliance with worker rights at garment factories. Above, a Cambodia facility.

The program, which Better Factories Cambodia began rolling out on Friday, comes as the global garment industry faces increasing pressure to improve conditions after the collapse of a garment factory in Bangladesh killed more than 1,100 people in April.

Accidents also have occurred in Cambodia recently, including two at factories in May, one of which left two people dead.

But Cambodia’s government and the country’s factory association have opposed the new program, saying it could wind up shaming only some factory owners and driving business to other countries where oversight is less rigorous.

The Better Factories program, set up by the U.N. and other groups a dozen years ago to improve conditions in Cambodia’s garment trade, is trying to reassert itself after coming under fire from some worker advocacy groups for not doing enough to improve factory conditions. Better Factories, among other things, inspects manufacturing facilities for problems such as child labor and unsafe conditions and offers training for factories to upgrade but has no enforcement power.

Jill Tucker, Better Factories Cambodia’s chief technical adviser, said she hoped that the new push to publicize compliance with worker rights and other standards not only will improve factory conditions in the Southeast Asian nation, but also will pressure people in the garment industry in other countries.

Getting support for the plan from all of Better Factories’ financial backers—which include the Cambodian government, the garment manufacturers’ association, unions, international buyers and foreign governments, such as the U.S.—has been a challenge, Ms. Tucker said.

Sat Samoth, undersecretary of state at Cambodia’s Labor Ministry, said the disclosure plan would violate a memorandum of understanding between the government and the U.N. International Labour Organization.

And the plan won’t help workers, Mr. Sat said. “If we disclose the names of the factories, and then the buyers stop purchasing the products, what will happen to the workers? They will lose their jobs,” he said. The government punishes factories that break the country’s labor laws.

Ken Loo, secretary-general of the Garment Manufacturers Association in Cambodia, called the Better Factories plan an example of “vigilante justice” and said that any change at factories has to be “demand-driven.”

“Consumers talk, talk, talk. But at the end of the day, they just buy the cheapest thing on the shelf,” he said.

Photo: Will Baxter/Bloomberg News

The Garment Manufacturers Association in Cambodia called the plan ‘vigilante justice.’ Above, workers leave a truck at the end of a workday in the country.

Starting this January, Ms. Tucker said, Better Factories plans to release information on a new website about the performance of all factories it has inspected at least twice regarding 21 issues, such as wages, worker rights, fire safety and treatment of unions.

Currently Better Factories Cambodia submits confidential reports to factories, whose business partners have the option to buy them. It also publishes public summaries that don’t name plants.

Under the new program, factories that have had three or more Better Factories inspections and still fall two standard deviations below the mean for compliance will be subject to an even higher level of disclosure. About 15 of the 450 factories the program monitors currently would fit that description. The public will see how they measure up against 53 legal requirements.

During the first year of the initiative, factories will get one opportunity to resolve any violations before they are disclosed. From then on, their performance will be published without negotiation.

Wal-Mart Stores Inc. the world’s largest retailer by sales, applauded Better Factories Cambodia’s plan. “We know that transparency is vital to make progress in improving factory conditions throughout the global supply chain, and can only be accomplished by working with stakeholders across the industry,” it said.

Sweden-based H&M Hennes & Mauritz AB also expressed support for the plan and said it wouldn’t lead the retailer to abandon any potentially problematic plants without good reason.

“H&M is aware of the challenges the factories in Cambodia face,” said spokeswoman Andrea Roos. The company doesn’t immediately stop working with factories if problems are detected, she said. As long as factories take negative findings seriously and commit to resolving issues, H&M prefers to maintain long-term relationships with them, Ms. Roos said.

Kong Athit, vice president of the Coalition of Cambodian Apparel Workers’ Democratic Union, said the Better Factories initiative would give the union more ammunition to pressure brands to force their factory partners to improve conditions.

Created a dozen years ago, the Better Factories program in Cambodia initially had a powerful weapon to encourage factories to improve: Under a 1999 trade deal, the U.S. offered to expand access to its market, which had quotas on garment imports, if Cambodian companies improved labor standards.

The 2005 expiration of the quota system left the Better Factories program without much leverage to pressure factories. It also enabled manufacturers to campaign successfully for Better Factories to stop naming them in their public reports, which, the companies said, could hurt their business, said Sandra Polaski, a deputy director general of the U.N. International Labour Organization.

Mr. Loo, of the manufacturers’ association, said the factories weren’t powerful enough to have forced the program into making the change.

Ms. Polaski and Ms. Tucker said the decision was a bad one that eroded the program’s progress in the country.

The ILO now is pushing for greater transparency in all of its monitoring programs globally. The organization’s Better Work Haiti program publicly discloses key portions of its factory audits, though the garment industry there is quite small.

In Bangladesh, following the Rana Plaza disaster, a consortium of more than 80 brands signed a fire and building-safety accord, which will publicly disclose factory performance.

David Welsh, Cambodia program director for the Solidarity Center, a nongovernmental organization affiliated with the U.S.-based AFL-CIO labor group, said that if any stakeholder in Cambodia doesn’t get on board with the new Better Factories proposal, “it’s a de facto admission that they either can’t or won’t monitor what’s going on in their factories and an admission that presumably, they suspect what’s going on doesn’t meet international labor standards.”

by Admin | Aug 5, 2013 | News

With all eyes on Bangladesh, it’s worthwhile to take a look at safety standards in garment factories in other countries. An International Labor Organization report discloses a disappointing decline in worker safety in Cambodia.

Credit- qz.com

For international retailers who have committed more than $250 million to improve factory workers’ safety in Bangladesh, the conditions in Cambodia should give them pause.

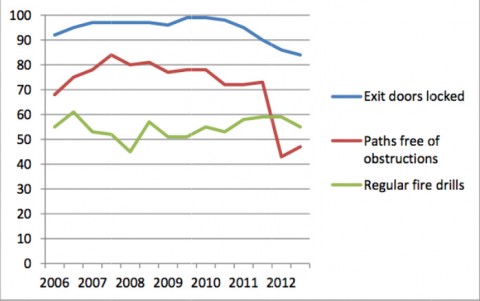

A bi-annual report (pdf) from the International Labor Organization-sponsored Better Factories program reveals a disturbing decline in working conditions in Cambodia’s garment factories. In the November 2012-April 2013 period, Better Factories found that the compliance to fire safety and worker health regulations were lower than what they were seven years ago.

Of the 155 factories assessed, 53% had obstructed access paths, compared with a little more than 30% in 2006, nearly 45% failed to conduct regular fire drills, and 15% kept emergency exit doors locked during working hours.

Credit-qz.com

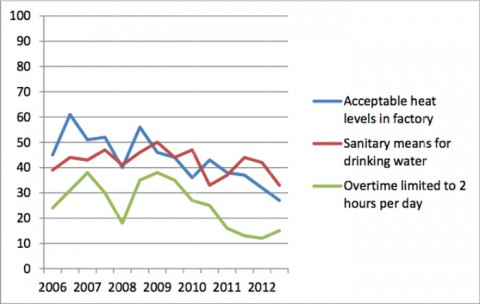

The report also highlights serious violations including excessive heat levels, shortage of safety masks, lack of proper equipment for handling chemicals and inadequate access to clean drinking water.

Cambodia is among the Southeast Asian countries that have benefitted from the double-digit wage increases and shortage of factory labor in China (paywall). The number of apparel export factories in Cambodia has surged from 185 in 2001 to 412 in April 2013 (pdf). Last year, the garment industry generated over $4.6 billon in exports, accounting for 84% of Cambodia’s total exports. The garment factories employ around 2.5% of Cambodia’s 15 million citizens and remittance payments from factory workers to families in rural regions sustain about 20% of the population, according to Japan External Trade Organization (pdf).

But the industry has been marred by mishaps and labor unrest in recent months. In May, accidents at two factories, including one that left two people dead when part of a shoemaking factory collapsed, highlighted unsafe conditions. Local media pounced on instances of workers fainting because of poor air circulation, and factory owners threatening to fire employees who refused to work overtime. Workers complained that the prevalence of short-term contracts lasting three to six months made it easier for employers to fire workers who joined unions (paywall) or demanded benefits like maternity leave.

A series of strikes over pay and conditions forced the factory owners to agree to a20% wage hike effective from May. Thanks to pressure by the Cambodian government, employers raised the monthly minimum wage from $61 to $75 and boosted employee healthcare stipends by $5 per month. Unions argue that, adjusted for inflation, those wages are on par with pay levels in the year 2000.