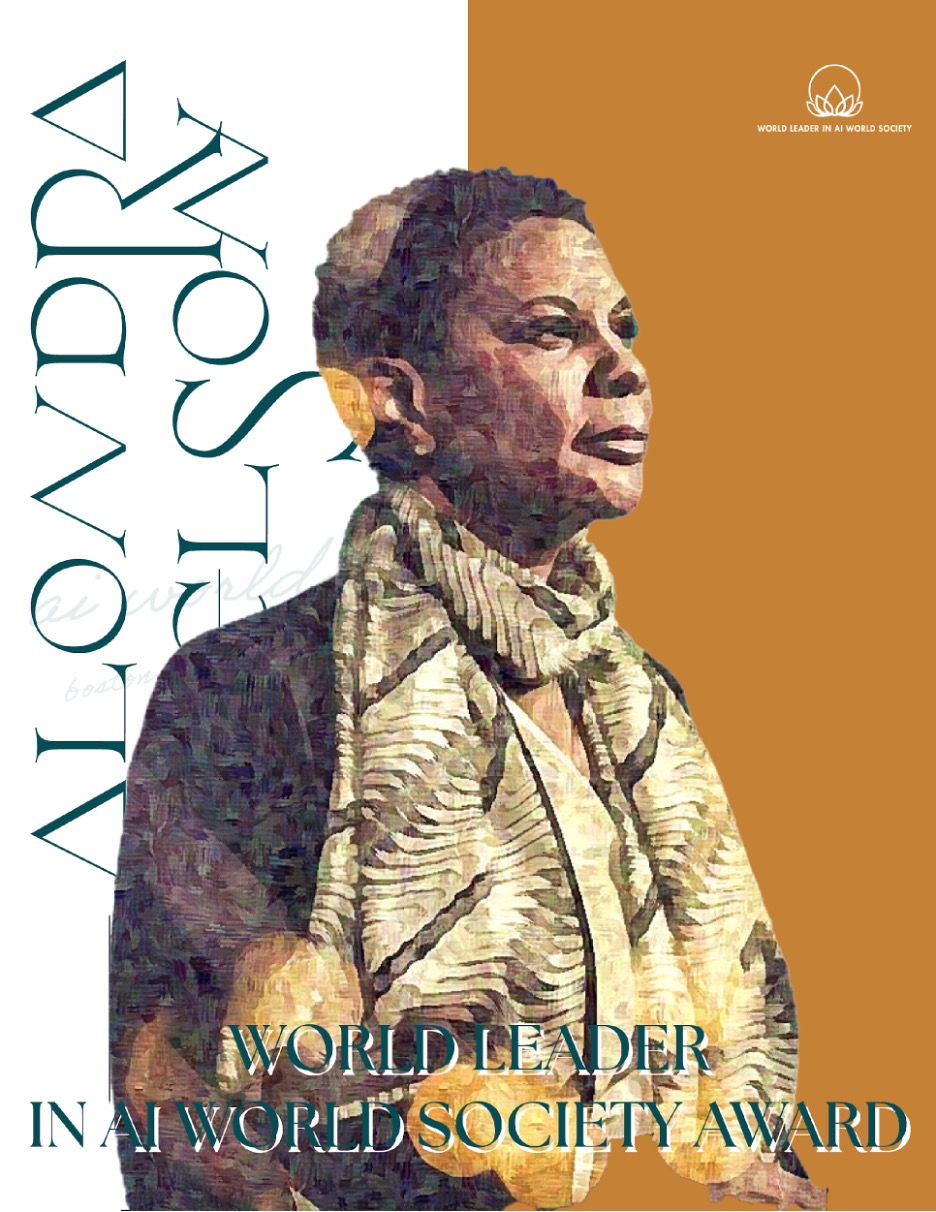

Before the conference to honor Dr. Alondra Nelson with 2024 World Leader in AIWS on April 30, BGF Chief Editor Minh Nguyen interviewed Dr. Nelson. Watch the full conversation on YouTube.

“Science and technology policy affects everything.”

When I threw an icebreaker question to Dr. Alondra Nelson in our conversation, I did not realize her response would encapsulate her governance philosophy so well. It may sound like a very obvious remark, but contained within is an insight that unfortunately not all lawmakers across the world understand.

This hidden importance of science and technology governance was the underpinning current carrying our conversation on April 30.

Nelson already knew she was foraying into policymaking and governance, as her appointment to the OSTP was already announced by the then-President-elect Biden in Delaware. This was the first time she would be involved in policy making.

But we were not not there to talk about public health or epidemiology, as vital as that field is, AIWS after stands for Artificial Intelligence World Society – and Nelson’s most renowned expertises were technology, AI, and society. In fact, one of the reasons she was appointed to the OSTP was due her possession of insights into the intersections of the aforementioned fields.

As deputy director, she had already begun advocating heavily for a framework on AI that would protect democratic principles, but a turnover at the office created an opening to turn her idea into reality. Nelson was appointed acting director after her predecessor’s resignation, but she was not there to be a lame duck. The AI Bill of Rights, which she had already envisioned in a Wired magazine op-ed in 2021, was finally put together and published in early October 2022. Although she did not express it verbally that day, one could tell that Nelson is extremely proud (and deservedly so!) of bringing the framework to the public. It was one of the first guidelines on AI governance and its impact vis-a-vis society and democracy issued by the government.

Perhaps interestingly, this framework was published a month before OpenAI released ChatGPT for public consumption and that phenomenon took the public debate and discourse by storm.

While her tenure was a short one, Nelson was firm in her belief that she had fulfilled her vision and stood proud of her achievements at the OSTP, as aforementioned. In fact, many of the guidance established during her leadership were beginning to get implemented in federal departments – the foundations she laid out are starting to come to fruition. The Boston Global Forum would agree with her self-assessment, as she was honored with the World Leader in AIWS Award for her work as deputy and acting director of the OSTP.

As scientists know though, both social and material, that progress can’t just be measured in years, but rather decades and even longer. At time of writing, the AI Bill of Rights was issued only two years ago. When I asked what she hope would become of the foundations her and the Biden administration planted this term, she wish that their AI policies will ultimate harness the power of AI in helping global issues in health and climate change, but still mitigate the externalities and harms that are already impacting livelihoods, such as racial bias in facial recognition or disempowerment of workers.

Even if she returned to academia after her time at the OSTP concluded, Nelson remains deeply involved in AI governance and policymaking. Rather than working for the White House, she was appointed to be the US Representative to the UN High Level Advisory Board, effectively switching DC for New York.

While working in this space, Nelson founded areas of potential cooperations for global AI governance – that “fundamentally, across different kinds of economic systems, political systems, political ideologies, when you’re thinking about AI, emerging technologies, I think what people agree on, and certainly in the US in a bipartisan way is they want the benefits of these technologies and they want to mitigate the harms,” she explained to me. Even though there are differing visions or geopolitical rivalries amongst member-states, this baseline of common understanding and aspiration can help bridge gaps of political divide and mistrust into a true global AI governance framework. In essence, the foundation of common humanity should be channeled into these global initiatives, Dr. Nelson believed. A desire for a common global framework is no less what one expects from a scientist.

These technologies do not inherently drive themselves toward an ethical or moral direction, but effective tech public policy and governmental guidance have the potential to enhance livelihood. In an era where the debate is dominated and polarized by opinions of AI doomerism and accelerationism, Dr. Nelson frames a third way: the synthesis to guide these technological and AI developments toward moral and ethical outcomes for society. One should not have to fear new technologies or AI, but civil society and government still need to mitigate their harms, for that could have disastrous consequences as well on the public and democracy. I recall a short exchange we had towards the end of our conversation:

MN: “From technology and science policy comes progress.“

AN: “Yes, sometimes.”

MN: “Hopefully, most of the time, that’s where we try to get.”

AN: “That’s where we’re at, got to go at. That’s what policy does, right? They steer towards this direction rather than that direction.”

After all, science and technology policies affect everything.

BGF Chief Editor Minh Nguyen and Dr. Alondra Nelson