Roger B. Porter

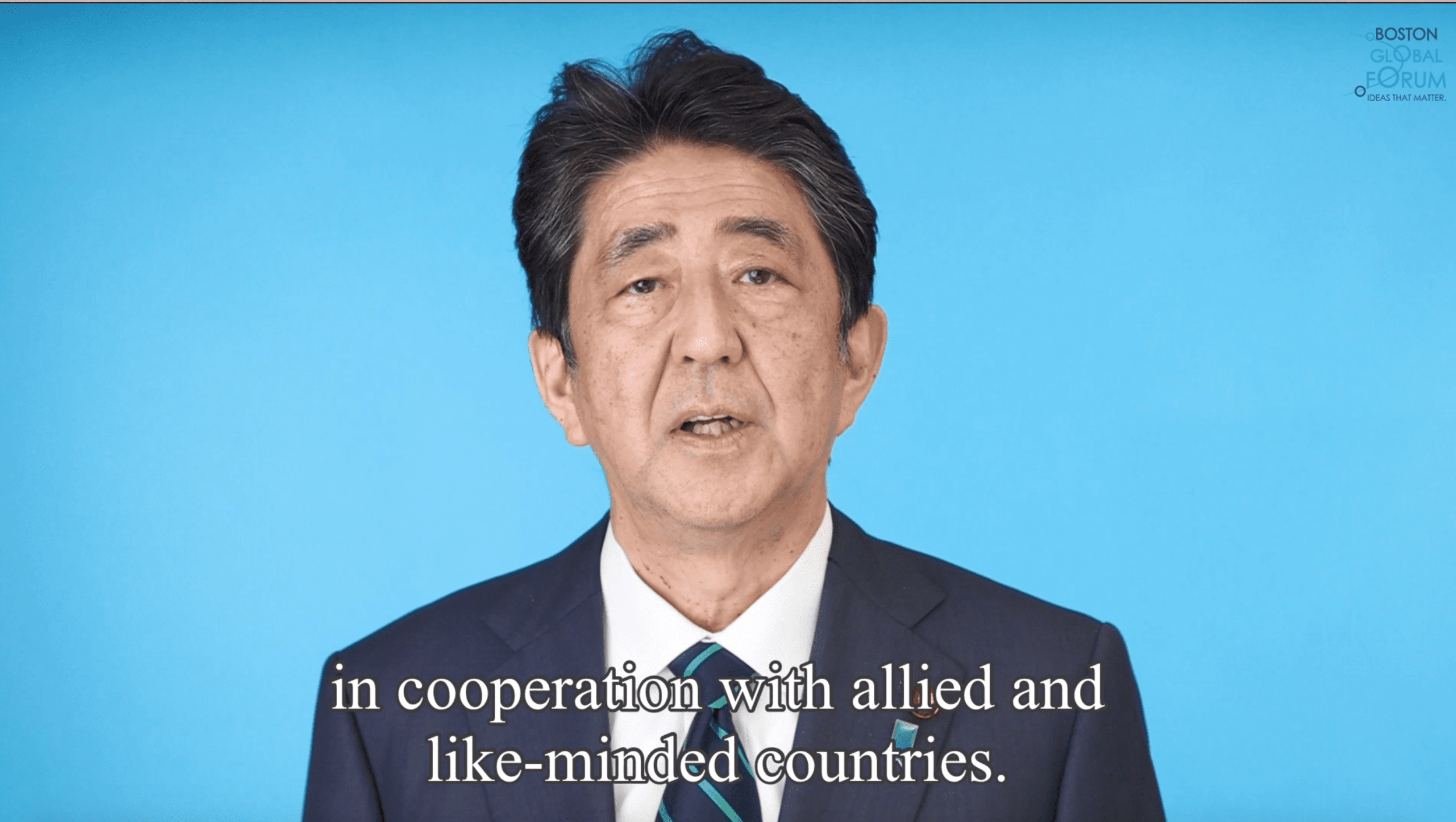

The stunning, senseless death of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe by an assassins’ bullet in Nara illuminates the vulnerability of political leaders. Abe’s legacy reminds us of the powerful influence of quiet diplomacy and of how one might think usefully about political leadership.

Quiet Diplomacy

Part of the measure of any administration’s success in foreign policy rests on the personal relationships established by leaders. Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, George H.W. Bush and Brian Mulroney are examples of the benefits that flow when leaders establish trust and admiration. Shinzo Abe, during his tenure as the longest serving Japanese Prime Minister in the last three quarters of a century, was as skilled as any foreign leader in establishing such relationships with George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump.

A major figure in Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party, Abe’s non-judgmental personality and cheerful disposition was key to his success. He was the first foreign leader to contact Donald Trump following his 2016 election, a courtesy that helped begin their relationship on a positive footing.

Matt Pottinger, the deputy national security adviser, confirms that Trump had more interactions with Abe than with any other foreign leader. They genuinely seemed to enjoy one another including their shared love of golf. Their lengthy discussions ranged from coordinating the response to North Korea’s nuclear and missile tests to fashioning a bilateral U.S.-Japan trade agreement. Concluded two and a half years ago, 90 percent of U.S. food and agricultural products imported into Japan are now duty free or receive preferential tariff access.

The Trump and Biden administrations have embraced Abe’s idea of a “free and open Indo-Pacific” and of a relationship of the Quad countries – the United States, Japan, India and Australia – designed to strengthen the rule of law and mutual security arrangements among other objectives. Much of Abe’s impetus for the Quad was his concern over the threat of a more aggressive and authoritarian regime in China which referred to the Quad as the Asian NATO.

Following the 2016 election, when the U.S. determined not to submit the recently negotiated Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) for congressional approval, Abe led the effort to conclude an agreement among the remaining eleven TPP countries winning support for a Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) that largely maintained the TPP agreement and left the door open should the U.S. choose to join.

Ideas matter

In 2015 Abe came to Harvard as part of a U.S. visit that included the first time a Japanese Prime Minister had addressed a joint session of Congress. His remarks were not merely perfunctory but included a sense of how he viewed the rising generation and especially the role that women could and should play in its leadership. He came across as an idealist without illusions answering questions forthrightly and with respect for those who asked them.

He included facts and statistics that demonstrated he understood the intricacies of a challenge and the range of viable options. At the same time, he neither denied nor dismissed those who advanced challenging questions. Not least, he punctuated his answers with a touch of humor noting in response to a question about the role woman can play that if Lehman Brothers had been Lehman Brothers and Sisters they might still be in business.

For political leaders, ideas can matter in two important senses. First, they provide a framework and vision of what is important and of goals that are worth pursuing. The status quo is buttressed with a good deal of inertia. Societies benefit from having a measure of stability. Such stability enables individuals and organizations to plan with confidence and can contribute to establishing trust and confidence in institutions and societies.

At the same time, great individuals, organizations and societies embrace a measure of dynamism. They do not settle into a comfortable complacency. They are willing to make changes that inevitably involve some risk. Finding an appropriate balance between stability and change is one of the most important tasks of leaders.

Shinzo Abe had a fresh vision for Japan and its place in the world. He recognized the challenge presented by the current leadership in China. He saw the value of a coordinated response by nations that found authoritarianism counterproductive and that embraced individual liberty, free market economic arrangements, and that guaranteed the rule of law.

Political leadership also involves sustained follow through to move the public, the permanent government bureaucracy and other officials at home and abroad. This often takes many years. Abe’s idea of a Quad involving Japan, the United States, India, and Australia as a bulwark in support of democracy, took more than a decade to take root and to be embraced by its members and acknowledged by China and others. His patience never failed.

Shinzo Abe was skilled in putting together alliances that respected distinctive national interests and yet could find much in the way of common ground. His success went well beyond his charm and charisma. It rested on determination, resilience, and pleasant persistence.

Roger B. Porter, IBM Professor of Business and Government at Harvard University, served as the assistant to the president for economic and domestic policy from 1989-93.

This essay was published in the Deseret News on July 14, 2022.