Fast and Flawed Inspections of Factories Abroad- The New York Times

If factory inspections and monitoring processes were already in place, then why did 1800 garment workers lose their lives within a span of a year? The New York Times uncovers the fatal flaws that have led to the loss of lives and trust in global supply chain economies.

NYT reporters Stephanie Clifford and Steven Greenhouse have the story.

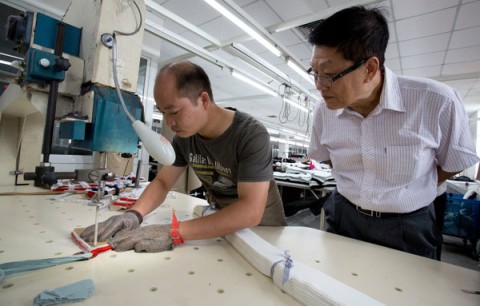

Zaichun Ye, right, a consultant at Verité in China, seeing if a worker is wearing chain mail gloves at a textile factory in Yuhang in Zhejiang province. Credit- The New York Times/ Jonathan Browning

Fast and Flawed Inspections of Factories Abroad

Inspectors came and went from a Walmart-certified factory in Guangdong Province in China, approving its production of more than $2 million in specialty items that would land on Walmart’s shelves in time for Christmas.

But unknown to the inspectors, none of the playful items, including reindeer suits and Mrs. Claus dresses for dogs, that were supplied to Walmart had been manufactured at the factory. Instead, Chinese workers sewed the goods — which had been ordered by the Quaker Pet Group, a company based in New Jersey — at a rogue factory that had not gone through the certification process set by Walmart for labor, worker safety or quality, according to documents and interviews with officials involved.

To receive approval for shipment to Walmart, a Quaker subcontractor just moved the items over to the approved factory, where they were presented to inspectors as though they had been stitched together there and never left the premises.

Soon after the merchandise reached Walmart stores, it began falling apart.

Fifteen hundred miles to the west, the Rosita Knitwear factory in northwestern Bangladesh — which made sweaters for companies across Europe — passed an inspection audit with high grades. A team of four monitors gave the factory hundreds of approving check marks. In all 12 major categories, including working hours, compensation, management practices and health and safety, the factory received the top grade of “good.” “Working Conditions — No complaints from the workers,” the auditors wrote.

In February 2012, 10 months after that inspection, Rosita’s workers rampaged through the factory, vandalizing its machinery and accusing management of reneging on promised raises, bonuses and overtime pay. Some claimed that they had been sexually harassed or beaten by guards. Not a hint of those grievances was reported in the audit.

As Western companies overwhelmingly turn to low-wage countries far away from corporate headquarters to produce cheap apparel, electronics and other goods, factory inspections have become a vital link in the supply chain of overseas production.

An extensive examination by The New York Times reveals how the inspection system intended to protect workers and ensure manufacturing quality is riddled with flaws. The inspections are often so superficial that they omit the most fundamental workplace safeguards like fire escapes. And even when inspectors are tough, factory managers find ways to trick them and hide serious violations, like child labor or locked exit doors. Dangerous conditions cited in the audits frequently take months to correct, often with little enforcement or follow-through to guarantee compliance.

Dara O’Rourke, a global supply chain expert at the University of California, Berkeley, said little had improved in 20 years of factory monitoring, especially with increased use of the cheaper “check the box” inspections at thousands of factories. “The auditors are put under greater pressure on speed, and they’re not able to keep up with what’s really going on in the apparel industry,” he said. “We see factories and brands passing audits but failing the factories’ workers.”

Still, major companies including Walmart, Apple, Gap and Nike turn to monitoring not just to check that production is on time and of adequate quality, but also to project a corporate image that aims to assure consumers that they do not use Dickensian sweatshops. Moreover, Western companies now depend on inspectors to uncover hazardous work conditions, like faulty electrical wiring or blocked stairways, that have exposed some corporations to charges of irresponsibility and exploitation after factory disasters that killed hundreds of workers.

The Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh, which killed 1,129 workers in April, intensified international scrutiny on factory monitoring, and pressured the world’s biggest retailers to sign on to agreements to tighten inspection standards and upgrade safety measures. While many groups consider the accords a significant advance, some longtime auditors and labor groups voice skepticism that inspection systems alone can ensure a safe workplace. After all, they say, the number of audits at Bangladesh factories has steadily increased as the country has become one of the world’s largest garment exporters, and still 1,800 workers there have died in workplace disasters in the last 10 years.

“We’ve been auditing factories in Bangladesh for 20 years, and I wonder: ‘Why aren’t these things changing? Why aren’t things getting better?’ ” said Rachelle Jackson, the director of sustainability and innovation at Arche Advisors, a monitoring group based in California.

Even with American and European companies appointing executives this summer to put in place a stricter regimen of inspections and safeguards under the new agreements, these efforts are limited to Bangladesh. Other leading garment-producing nations, like China, Honduras, Indonesia, Pakistan and Vietnam, are not getting such stepped-up attention or expanded inspections. Thousands of factories in those countries will no doubt continue to be reviewed through the perfunctory “check the box” audits.

Trouble With Audits

Factory monitoring companies have established a booming business in the two decades since Gap, Nike, Walmart and others were tarnished by disclosures that their overseas factories employed underage workers and engaged in other abusive workplace practices. Each year, these monitoring companies assess more than 50,000 factories worldwide that employ millions of workers. Walmart alone commissioned more than 11,500 inspectionslast year. Spurred by heightened demand for monitoring, the share prices of three of the biggest publicly traded monitoring companies, SGS, Intertek and Bureau Veritas, have all increased about 50 percent from two years ago.

The inspections carry enormous weight with factory owners, who stand to win or lose millions of dollars in orders depending on their ratings. With stakes so high, factory managers have been known to try to trick or cheat the auditors. Bribery offers are not unheard-of. Often notified beforehand about an inspector’s visit, factory managers will unlock fire exit doors, unblock cluttered stairwells or tell underage child laborers not to show up at work that week.

Unauthorized subcontracting, or farming work out, to an unapproved factory (as was the case for the Quaker Pet Group order in China), is “very, very common,” according to Gary Peck, founder and managing director of the S Group, a design and sourcing company based in Portland, Ore.

Though almost all retailers prohibit the practice in their contracts, suppliers still do it to save money, speed production and meet high-volume orders.

And even inspections conducted at authorized factories can be deeply flawed. When NTD Apparel, a contractor for Walmart that is based in Montreal, hired a firm to inspect the Tazreen factory in Bangladesh before 112 workers died in a fire in November, the monitors’ questionnaire asked whether the factory had the proper number of fire extinguishers and smoke detectors on each floor. But it did not call for checking whether the factory had fire escapes or enclosed, fireproof stairways, which safety experts say could have saved lives.

“If it’s a check-the-box inspection, you better have the right boxes to look at,” said Daniel Viederman, chief executive of Verité, a nonprofit monitoring group.

Sajeev Jesudas, president of UL Verification Services, which conducted the Tazreen audit, said inspecting for fire escapes and fireproof stairways was “the responsibility of the local building inspectors.” Bangladesh has been faulted for having far too few officials to inspect factories.

Greg Gardner, the chief executive of Arche Advisors, said Western retailers and brands often seek different levels of audits. Some, like Levi’s and Patagonia, want rigorous — and costly — audits, while others prefer limited, inexpensive audits that will not jeopardize relationships with favored suppliers.

Audits can be very brief. A single inspector might visit a 1,000-employee factory for six to eight hours to review all types of manufacturing issues, like wages, child labor or toxic chemicals. Some auditors receive only five days of training, whereas the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration requires three years of training and experience assisting inspectors before employees can lead an inspection of a sizable factory in the United States.

In the Rosita case, after the workers went on their rampage, the Western companies that bought the factory’s knitwear grew alarmed. So Rosita’s owner, South Ocean, a conglomerate based in Hong Kong, commissioned a new inspection.

That inspection, conducted by Verité, which is based in Massachusetts, was a scathing broadside. Verité’s monitors found “ongoing physical abuse” and “verbal and psychological harassment,” with managers compelling workers who arrived late to stand for “many hours without rest.”

Verité’s three-day inspection found errors in calculating wages, chemical containers labeled only in English and unreasonably high production quotas for which workers were disciplined or fired for not meeting. The inspectors noted that workers “often face harsh treatment,” including jeering from managers if they requested sick leave or annual leave. The monitors also found that managers had fired employees for missing work because of a death in the family and that security guards had beaten workers involved in union and protest activities.

Mr. Viederman of Verité said the earlier inspection, performed by a major monitoring firm, SGS, demonstrated the shortcomings of checklist audits. The SGS inspection involved a one-day visit, largely seeking yes-no answers, probably for a modest fee.

He noted that SGS had interviewed employees only inside the factory, where workers were often unlikely to speak candidly, and not outside — for instance, at bus stops or at home, where workers might open up.

Charles Kernaghan, executive director of the Institute for Global Labor and Human Rights, was shocked when he read the SGS inspection report for Rosita. “The auditors were saying everything was in perfect order,” he said. “It shows how ineffective these monitoring organizations can be.”

Effie Marinos, sustainability manager at SGS, defended her company’s findings. She said SGS had followed the inspection protocol developed by the Business Social Compliance Initiative, a factory certification group for European businesses.

Ms. Marinos said the protocol for Rosita did not require interviewing workers outside the factory, a practice that she cautioned could undermine a relationship between a Western company and its suppliers.

“You don’t want to start the whole approach with a lack of trust, that they are trying to fool you, that they are behaving unethically,” she said. “It can sour an entire relationship.”

Bypassing Inspection Rules

The Walmart purchase orders read “Ethical Standards Required.”

In mid-2011, the Quaker Pet Group, whose biggest customer was Walmart, began looking for cheaper factories where its trendy dog clothes could be made, according to a former Quaker employee who requested anonymity for fear of reprisal from Quaker. The company has also sold its goods to Petco, PetSmart and smaller retailers.

Quaker settled on a plant called Jiutai Bag and Gift Factory in Dongguan, Guangdong. After visiting the site, Quaker’s president, Neil Werde, sent a note to a Jiutai representative in June 2011. “I was pleased with your factory,” Mr. Werde wrote, according to an e-mail shared by the former employee. “Good luck on the Walmart inspection.”

That inspection did not occur. Quaker officials became concerned that Jiutai would not be able to pass an inspection, the former employee said.

But there was a workaround. While Jiutai would make the garments, Quaker would fill out order forms to say that the items had been made by Ease Clever Plastic Manufactory, then an approved Walmart supplier. Ease Clever is an established manufacturer that ships products to Target and other large companies, according to the global trade database Panjiva. Jiutai, by contrast, had only one recent listing in the database, for a small shipment to Puerto Rico in 2011.

The stickiest issue was how to get the clothing made by Jiutai past Walmart inspectors. An inspection at Ease Clever was scheduled for September 2011, when the Walmart representatives would check that the dog outfits were being manufactured there, the former employee said.

Jiutai simply took the clothes to Ease Clever, according to the former employee. Those moves were outlined in a later e-mail from a Jiutai representative to Mr. Werde.

“The Walmart inspectors showed up and said, ‘Oh, they are being made here.’ It’s not as challenging as you would think,” the former employee said. “You have your finished-goods area and just show them the cartons being packed out.”

In an e-mail to Mr. Werde, the Jiutai representative, identified as Mr. Hu, detailed how the setup had worked as he pushed Quaker for payment.

In July, Mr. Hu wrote, a company based in Hong Kong called KYCE, apparently acting as a liaison, helped arrange an order for the Christmas dog clothes. “JiuTai only make the clothes,” Mr. Hu wrote.

In September, “we hang the clothes” in display cases and “send to Ease Clever warehouse for Walmart during inspection,” Mr. Hu added, including photographs of the costumes. After the inspection, the clothes went back to Jiutai, and Jiutai, after making final adjustments, packed and delivered the clothes to the shipping terminal, Mr. Hu wrote. Mr. Hu and KYCE representatives did not respond to multiple e-mails seeking comment.

Throughout September, according to Walmart purchase orders, Quaker shipped $2.1 million worth of pet outfits from Yantian, China, to various American ports. The purchase orders list Mrs. Claus dresses, Santa suits and reindeer suits — the exact outfits Mr. Hu of Jiutai said he had made at his factory and then photographed. But the purchase orders list Ease Clever as the supplier, not Jiutai.

Contacted by telephone last month about the inspection and shipment, Jay Xie, a sales manager for Ease Clever, said the company had allowed the use of its Walmart certification. “His factory had not yet been audited — he used my factory because it was already audited,” Mr. Xie said of the Jiutai factory manager. Mr. Xie said this had happened only once, as a friendly act to help a fellow manufacturer.

The shipment, though, was late, according to the former employee and Mr. Hu’s e-mail. And soon after Walmart started selling these items, Quaker began receiving complaints, according to the former employee. When Walmart conducted a quality test on the Mrs. Claus dress, it found holes, and the outfit failed the test. Walmart executives then summoned Quaker employees to its sourcing office in Shanghai for an explanation, but Quaker did not disclose the subcontracting to Walmart at that time, the former employee said.

In March 2013, Walmart received a tip, via its global ethics hot line, about the unauthorized subcontracting and looked into it.

Kevin Gardner, a spokesman for the company, confirmed that subcontracting in this case occurred in 2011, and that Walmart officials “met with the supplier after the investigation to go through the findings and reinforce what our expectations are pursuant to subcontracting.”

Even though Walmart was alerted to the case nearly two years after the products were made and only after a hot line tip, the retailer pointed to the episode as an example of how its investigation and compliance system was working, not faltering.

“We investigated. We talked with the supplier. We think this does show the processes were in place,” Mr. Gardner said.

In January of this year, Walmart established a “zero tolerance” policy, saying it would drop suppliers who used subcontractors without the company’s approval. Walmart adopted the policy after garments headed to the company were found in the fire debris at Tazreen, an unauthorized factory.

Quaker and Mr. Werde declined to comment. The pet specialty company remains a Walmart supplier, Mr. Gardner said.

Cat-and-Mouse Games

The question-and-answer sheet that the factory’s managers distributed to all their employees was explicit: if an inspector ever asked, “Are there injury records?” they were to answer, “Have not heard of any work-related injuries.”

And if an inspector asked, “Any corporal punishment in the factory?” the employees were to reply, “No.” If monitors inquired about underage workers at the plant, employees were coached to respond, “Employment for those less than 16 years old is prohibited.”

This sheet, prepared by managers at a Chinese factory and obtained by The Times, had one purpose: to trick inspectors.

Supply chain experts and monitors say that far too often, factory managers play cat-and-mouse games with inspectors because they are desperate to avoid a failing grade and the loss of a lucrative stream of orders.

The experts provided real-life examples. To avoid appearing illegally overcrowded, one factory moved many machines into trucks parked outside during an inspection, a monitor said. Whenever inspectors showed up at certain plants in China, the loudspeakers began playing a certain song to signal that underage workers should run out the back door, according to several monitors. During inspections in India, some factories displayed elaborate charts detailing health and safety procedures that, like stage props, were transferred from one factory to another, another monitor said.

For monitoring companies with major retailing clients, the auditing regimen can be nonstop. The territory itself is daunting — 5,000 factories produce garments in Bangladesh alone. A retailer that uses 1,000 factories worldwide might want to pay no more than $1,000 an inspection — that could mean a one-day, check-the-box audit — instead of $5,000 for thorough, five-day inspections. That would cost $1 million instead of $5 million.

“You have this intense price pressure downward on these inspection firms, turning them into a commodity business,” said Mr. O’Rourke of the University of California, Berkeley.

Auret van Heerden, president and chief executive of the Fair Labor Association, a nonprofit group that Apple uses to monitor its Foxconn factories in China, said many inspectors were too rushed. “Many are doing a factory a day, and many auditors, more than one factory a day,” he said. “They’re on a plane and going to a new city the next day. They don’t have much time to think about it or dwell on it.”

Despite some improvements, many supply chain experts say monitoring has inherent shortcomings. Not long ago, Nike and other sporting goods companies were shaken by revelations that children, ages 5 to 14, toiled up to 11 hours a day making soccer balls for them in Sialkot, Pakistan.

A study found that half of Pakistan’s soccer ball workers were making less than the minimum wage, with many stitching the balls’ panels together at home, making it hard for factory monitors to unearth such violations.

Nike responded by requiring its main contractor there, Silver Star, to consolidate production in one big factory. Knowing how skilled many contractors have become at gaming the monitoring system, Nike took an unusual step and ordered Silver Star to set up a system of elected worker representatives who would be charged with speaking up about safety problems, wage violations or other issues.

“We’ve learned that monitoring alone isn’t enough,” said Greg Rossiter, Nike’s chief spokesman.

Mr. van Heerden said, “You can never visit facilities often enough to make sure they stay compliant — you’ll never have enough inspectors to do that. What really keeps factories compliant is when workers have a voice and they can speak out when something isn’t right.”

Still, after a string of fatal disasters and repeated failures in uncovering serious violations, many experts doubt that even a highly organized and supervised inspection industry can improve factory conditions in country after country. Heather White, a research fellow at Harvard and a longtime factory auditor, said, “It starts as a dream, then it becomes an organization, and it finally ends up as a racket.”